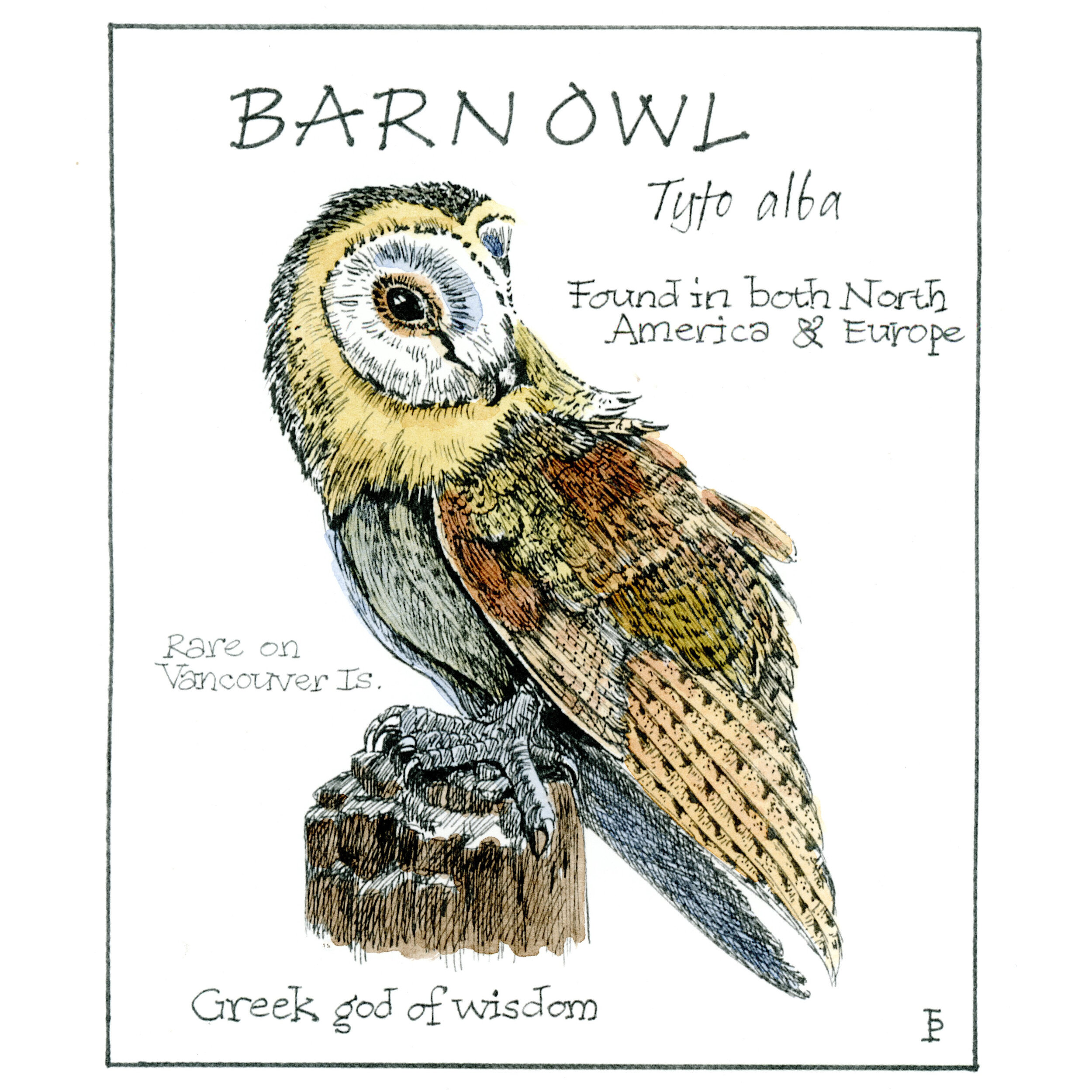

Illustration by Briony Penn

Summary

Who, or what, is a Naturalist? With the help of author Briony Penn, we trace the intertwined stories of two pivotal characters in the modern environmental movement: Cecil Paul (Wa'xaid) & the late Ian McTaggart-Cowan. These larger-than-life figures inspired a generation to reconnect, intellectually and spiritually, with the natural world. Associate producer Fern Yip investigates what it all means to the youth of today.

Adam and Fern are your hosts on this episode. Mendel is busy making a series of bonus mini-episodes on the weird and wonderful world of Fungi exclusively for our supporters on Patreon. Support the show and get access to these episodes for as little as $1/month.

Show Notes

This episode features Briony Penn, Arnaud Gagne, Matt McKinney, Jean-Claude Catry, and kids from the WOLF Program at Wisdom of the Earth School (Sahara, Matilda, Isaac, & Maya)

To find Briony’s books, go to www.brionypenn.com. Also, for more on the ‘B’, check out ‘The Bison and the B’, from CBC Ideas.

For more information on Wisdom of the Earth School, visit www.wisdomoftheearth.ca.

Music in this episode was produced by kmathz, VALSI, Luke and Charissa Garrigus, Claude Debussy, Leave, Sunfish Moon Light.

Special thanks to Briony Penn, Simone Miller, Tori Elliot at Touchwood Editions, the entire team at the Wisdom of the Earth School, Ilana Fonariov, and the Access to Media Education Society.

A lot of research goes into each episode of Future Ecologies, including great journalism from a variety of media outlets, and we like to cite our sources:

Penn, B. (2015). The Real Thing: The Natural History of Ian McTaggart Cowan. Nanoose Bay CA: Heritage House Publishing.

Penn, B. (2019). A Year on the Wild Side: a West Coast naturalists almanac. Victoria, British Columbia: TouchWood Editions.

Paul, C., & Penn, B. (2019). Stories from the Magic Canoe. Vancouver, BC: Heritage House.

This podcast includes audio recorded by Herbert Boland, protected by a Creative Commons attribution license, and accessed through the Freesound Project.

You can subscribe to and download Future Ecologies wherever you find podcasts - please share, rate, and review us. Our website is futureecologies.net. We’re also on Facebook, Instagram, iNaturalist, Soundcloud and Youtube. We’re an independent production, and you can support us on Patreon - our supporters have access to bonus monthly mini-episodes and other perks.

Future Ecologies is recorded on the unceded territories of the Musqueam (xwməθkwəy̓əm) Squamish (Skwxwú7mesh), and Tsleil- Waututh (Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh) Nations - otherwise known as Vancouver, British Columbia. It is also recorded on the territories of the Penelakut, Hwiltsum, and other Hul’qumi’num speaking peoples, otherwise known as Galiano Island, British Columbia.

Transcription

[Rhythmic, gentle wave sounds with light xylophone]

Introduction Voiceover 00:00

You are listening to season two of Future Ecologies.

[Xylophone ends slowly, descending]

[Wave sounds continue, as a mdeditative buzzing background noise begins]

Briony Penn 00:10

One day at the end of February, I decided to go float around in a canoe and watch clouds. I'm not very good at meditating, and this seemed more interesting than floating cross legged above a cushion. This is all in aid of trying to calm my anxiety about the state of the world, climate change, and mass extinctions. I wanted to rest my eyes on nothing but gray expanses of fluffy clouds, the odd gull, and any natural creature that we had no claim of possession upon. The Romans, who seemed to claim everything, refer to that which, quote "belongs to all" unquote, as Communia Omnia, which also sounds like the perfect meditative chant. The day was calm, overcast, and mild. I pushed myself off, lay down in the canoe and floated out to sea on the gently ebbing tide to communia with the omnia.

[Rocking boat noises]

Briony Penn 01:12

The beauty of bobbing along the bottom of a canoe is that no one knows you're in there. Onlookers just see a piece of old fiberglass, which isn't good for salvage, or salvation for that matter. I had planned to float for the full ebb of the tide. Six hours out, and then paddle home with the flood. Feeling at one with the pull of the moon. After one hour, I'd exhausted the possibilities of Communia Omnia as both a concept and a chant. I had failed to spot even one Glaucous-winged gull, as all the seabirds were either obscured in the mist or bobbing around the canoe, waiting for the eagles to start a feeding frenzy on me. I was in the process of reconciling myself to not having what it takes to reach Nirvana, when there was a gentle rocking of the canoe. I assumed it was the wind picking up and felt relieved that I could now go home with a valid excuse of inclement weather. That was when I heard the first loud exhalation of breath.

[Sea Lion noises]

Briony Penn 02:21

Like a gunshot. It was a mixed pride of Steller and California sea lions punching through the water, six meters off my bow. Sea Lions this time of year are looking for herring and the salmon that chase herring. I was obviously intercepting the food chain. A Steller bull can weigh up to 1000 kilograms. The California bulls are featherweights at 400 kilos, but they all have the same big appetites and teeth. The Steller winter along the coast before congregating in the spring at their rookeries or breeding ground islands off the north end of Vancouver Island and south of Haida Gwaii. The California started coming up the coast over the winter years ago chasing the diminishing herring populations. After the predations of automotive magnate Jimmy Patterson, who's had a monopoly on the herring and salmon fisheries, these southerners have been known to toss balls and algorithms on their noses. So I was hoping they weren't looking for some practice with my canoe. They quickly dispersed, and once again, I was adrift in the void. The only sound was the blood pumping around my body at five times the normal rate. According to the indomitable law of nature, where there is food, there are predators, and sea lions are themselves prey to transients posit killer whales known as Bigg's Killer Whale. Another fact that I can accurately relate is that from a supine position in a canoe, the two meter dorsal fin of a male killer whale is visible from four meters off the stern.

[Suspenseful music]

Briony Penn 04:06

Bigg's differ from the southern resident killer whales in a variety of ways other than being vagrant. The most important difference is that they hunt sea mammals, whereas the SRKW's are content to spend their day sharing Chinook salmon with their pod if they can find one. The Bigg's don't vocalize like their cousins because they rely on stealth to hunt. It was too early for Chinook. So my company was unlikely to be members of the endangered J, K, and L pods that have charmed everybody around the Salish Sea. Everybody except the oil and pipeline companies and other predators. This possibility alarmed me somewhat from the bottom of my canoe. The Bigg's killer whale's method of hunting is to dive down deep until they see the shadow of the sea lions above them, then race up at breakneck speed and stun the sea lions with their impact.

[Anxious music]

Briony Penn 05:03

In my nervous state, I dwelt upon the fact that the shadows of sea lions and canoes are not widely divergent.

Briony Penn 05:10

Suddenly another smaller dorsal fin hove into view and came straight for me. Two males were stationed on either side like sentinels, and the smaller female was approaching the canoe slowly. By her side, I could make out the small form of a baby close up beside her. About three meters off the stern they sounded and glided under the canoe, so that I had a full view of them. Her dorsal fin grazed the hull, and I found myself on my knees for the second time that day.

[Music calms, rocking boat noises begin. Meditative, buzzy background music begins again].

Briony Penn 05:50

I didn't wait for the tide to turn. I paddled home very rapidly in case the heavens were also gonna lay on a breaching humpback whale, since they, too, have returned to the Salish Sea. The truth is, my depression lifted because there is still some Communia Omnium living in the Salish Sea for the time being.

[Bright, inspiring music crescendos]

[Whale noises]

Adam Huggins 06:27

That's beloved author, activist, and naturalist, Briony Penn, reading a story from her recently reissued classic: A Year on the Wild Side.

Fern Yip 06:36

Her peaceful boat rest was less seasick than mine.

Adam Huggins 06:42

And this is my friend and one of our associate producers for season two. Fern. Yep, Hi Fern.

Fern Yip 06:47

Hi there, Adam

Adam Huggins 06:48

And you, you actually kayaked over here from Salt Spring Island this morning.

Fern Yip 06:51

I did paddle over in the Trincomali Channel.

Adam Huggins 06:55

Fern is sitting in for Mendel today in the studio with me to interrogate the idea idea of the naturalist. What does it even mean? And what to make of this strange breed?

Fern Yip 07:06

All right, I didn't sign up for interrogation or breeding

Adam Huggins 07:11

[laughs]

Fern Yip 07:11

...but I am happy to chat.

[Music crescendos]

Introduction Voiceover 07:13

Broadcasting from the unceded, shared, and asserted territories, of the Penelakut, Hwiltsum, and other Hul'qumi'num speaking peoples, this is Future Ecologies. Where your hosts, Adam Huggins and Mendel Skulski,

Adam Huggins 07:28

and our wonderful associate producers

Introduction Voiceover 07:30

explore the shape of our world through ecology, design, and sound.

[Intro music crescendos, then abruptly ends]

[Wave noises begin]

Adam Huggins 07:46

A few months ago, Fern and I met Briony at her cozy home on Salt Spring Island in the Salish Sea, to talk about not one, but two biographies.

Fern Yip 07:56

We might as well call them life histories.

Adam Huggins 07:58

Two life histories, that she's recently published on two seemingly very different human beings. And to find out , since Future Ecologies is secretly a self-improvement podcast, at least for me, (don't tell Mendel)

Fern Yip 08:11

You are on radio, you know.

Adam Huggins 08:13

..to find out just how she manages to do all this writing and naturalizing and still get her boots wet.

Briony Penn 08:20

Well, you've kind of raised a well-kept secret of mine, which is I say, I'm busy to a lot of people, but actually, I'm not. I just go get in my boat and go-- I spend a lot of time in my rowboat, you can see all my oars. I'm the only person who has four pairs of oars.

Adam Huggins 08:40

I was gonna say, one side of your house is oars. The other side is gumboots.

Briony Penn 08:43

[Laughs] Yeah, so you can tell where I spend my time. And I just tell people, I'm really busy, and they all think I'm doing something productive, but I'm not. But then I guess you could question what productive is defined as in our society.

Adam Huggins 08:58

Being around Briony makes me question my own definition of productivity and the manic pace at which I sometimes live. Still, she's actually written a lot in these past few years about these two...you might call them naturalists.

Briony Penn 09:12

So, I had this incredible privilege of interviewing two older men for the purposes of writing their biographies, and they couldn't have been more different and more similar.

Adam Huggins 09:27

The first is the Canadian zoologist and conservationist, Ian McTaggart Cowan, and the second Xenaksiala elder, Wa'xaid, or Cecil Paul. And it was in documenting and considering the lives of these two men that Briony started to drill down into the idea of the naturalist.

Briony Penn 09:44

So, when I was trying to come up with the definition of naturalist I thought, well, let's go back to the source, to some of the elderly naturalists. And one of them was Bob Weeden. And Bob Weeden was a student of Ian McTaggart Cowan's. And he, and Cowan, and a whole lineage before him-- dating all the way back to sort of Darwin's time-- define themselves as naturalists. And this is how he, he described it to me.

[Music, bird calls]

Briony Penn 10:11

The naturalist comes into the natural environment with everything open. The naturalist doesn't leave anything behind. A scientist goes there with a job to do, which is to reveal truths that in the scientific sense can be proved. The scientist is supposed to leave his self behind and only engage that part of the mind that is a computer. Whereas, the naturalist is open to a spiritual dimension, is open to being emotionally moved and can say so, and is open to being reminded of the metaphors that are all around us in nature of the nonhuman world, and this veneer of artifact that we live in. So it's kind of an interesting fact that you raise the idea of spiritual and scientific in the same breath because for most scientists, that would be the death knell on their career, which is why in the book on McTaggart Cowan, a great part of it was looking at the secret society that formed the scientists who were also spiritual men. They knew that they had a strong emotional attachment and indeed a spiritual attachment to the natural world. And for many of them having gone through World War One and, and various traumas like losing their fathers or, you know, depression or whatever traumas they had gone through. Um..they found that the spiritual dimension of nature is what healed them. They were able to deal with their post-traumatic stress disorders by being out in the natural world. They weren't about to say that to their bosses or the scientific institute that they worked for, or, you know, and sometimes not even their their wives or, you know, companions or friends.

Fern Yip 12:00

Okay, Adam, I have a bit of a confession to make. I was outside in nature quite a lot this summer

Adam Huggins 12:08

With your oars and gumboots?

Fern Yip 12:09

No, with my ropes and harnesses.

Adam Huggins 12:11

Of course.

Fern Yip 12:13

Okay, so the confession is, I didn't get around to reading The Real Thing. I mean, it's like over 500 or 700 pages?

Adam Huggins 12:21

Uh huh, you weren't able to get through that behemoth that is Briony's biography of Ian McTaggart Cowan?

Fern Yip 12:26

Yeah, I mean..no, I didn't. But can you give me the Sparknotes version? Who was in McTaggart Cowan?

Adam Huggins 12:35

Sure. yeah. So, Ian McTaggart Cowan is often called the father of Canadian ecology. And if you're looking back at the history of conservation and biology in Canada, he's at the center of so many important moments. His teachers and eventually, his students basically read like a who's who of the biological community.

[Music stops]

Adam Huggins 12:56

Like the human biological, the, the biologist community

Briony Penn 12:59

He in fact, hired David Suzuki. So, when you look at his lineage there's just virtually no environmentalist in in Canada that doesn't trace his lineage to Ian McTaggart Cowan, and Ian McTaggart Cowan traced his lineage through early scientists in Canada and then back into Britain.

Fern Yip 13:16

He's pretty much like the David Attenborough of Canada.

Adam Huggins 13:18

Exactly. He actually had his own TV series, The Web of Life, which was sort of like the Planet Earth of its day. If Planet Earth was shot and black and white, and included long, awkward shots of David Attenborough in a suit, sitting at a desk, talking very slowly.

Media Clip 13:33

[Ian McTaggart Cowan] Hosts of small living creatures, darting about.

[Moody archival music]

Media Clip 13:38

[Ian McTaggart Cowan] This weird beast is the young stage of a water beetle.

Fern Yip 13:45

I guess attention spans were pretty different in those days. All right, so what's the rest of the Sparknotes?

Adam Huggins 13:52

Right. Um. So, I learned a whole bunch of things. For one, Cowan was a lifelong hunter from a very young age. Largely for subsistence purposes, but also for science. Basically, back in the day, you would just go out and collect animals by by shooting as many animals as possible.

Briony Penn 14:12

[laughs] By shooting as many animals as possible.

Briony Penn 14:15

But he also shot animals, but each one in a way like...

Fern Yip 14:19

[laughs] They had different purposes.

Briony Penn 14:20

It was a different purpose.

Fern Yip 14:21

Different purpose

Adam Huggins 14:23

I was just thinking to myself, reading that, you know, 100 years ago, I would have been shooting these things.

Briony Penn 14:28

You would have been, and you would have been up close, and you would have known these animals so intimately. You could have told the difference of a fur of a small mammal blindfolded, which is what Cowan could do. He could tell, "Oh, that's a muskrat".

Media Clip 14:43

[Ian McTaggart Cowan] Here we have the world of the muskrat.

Briony Penn 14:45

"No, that one's a Long-tailed vole. That one...", like he can tell the mammals from, from feeling them.

[Music ends abruptly with a click, then begins again].

Fern Yip 14:56

Well, that's not what's in my field guide these days. Mostly, we just look at pictures.

Adam Huggins 15:01

Yeah, except for entomologist, they actually still kill lots of bugs to do their work. But I can't talk because I kill loads of plants all the time.

Fern Yip 15:09

But you grow more!

Adam Huggins 15:10

That's right, two sides of the same coin, which I guess is the point I'm trying to make. He wasn't just a scientist or an educator or a statesman. He was a hunter and a lover of nature with a physical and a spiritual, not to mention a visceral and gastronomical connection with the more than human world. Today, to a certain extent, and especially back in the day, it was really dangerous for a scientist to express any personal connection with nature. You could lose your credibility, your objectivity, or worse, your career. And this is the most remarkable thing that Briony's research uncovered.

Fern Yip 15:49

What's that?

[Eerie music crescendos]

Adam Huggins 15:50

Cowan was part of a secret society called "The B".

[Music stops]

Fern Yip 15:58

Okay, so what is "The B"?

[Calm, orchestral music (Claire de lune)]

Adam Huggins 16:00

"The B" is short for "The Brotherhood of the Venery".

Fern Yip 16:03

Right, okay, like venison.

Adam Huggins 16:04

Right. Which actually used to refer to many different kinds of meat, and now has only recently become the name for deer meat.

Fern Yip 16:10

Or a venereal disease.

Adam Huggins 16:13

Definitely a different route [laughs]. Anyway, so, Briony discovered the existence of The B in a set of files that Cowan left behind when he passed away. In a folder labeled...

Fern Yip 16:25

"The B"...

Adam Huggins 16:26

Exactly. It's been around for almost 100 years. But until Briony found this folder, nobody knew about it.

Briony Penn 16:34

It was started in 1926. So it's nearly 100 years old, the organization. It's a secret society so we don't know where it is.

Adam Huggins 16:41

Uh huh.

Briony Penn 16:42

[Laughs]

Adam Huggins 16:42

Can we set the scene at all? Are they, are they in this parlor somewhere smoking cigars or..?

Briony Penn 16:46

Yeah, the scene is that they would meet once a year. They would meet at wildlife conferences where they were going anyway as scientists, and then they would rent a room somewhere, and they would always do it around winter solstice.

Adam Huggins 17:00

They would sit down, and one of them would read an essay that they prepared, especially for the occasion.

Fern Yip 17:05

Okay, Who were the "they"?

Briony Penn 17:07

Um, the sort of fathers of ecology and conservation like Aldo Leopold and McTaggart Cowan and people like that, they were all in this secret brotherhood. So, Aldo Leopold's Sand County Almanac book, which was published after he died, was a collection of the essays he had prepared for the Brotherhood, for the B.

Fern Yip 17:24

[incredulously] Aldo Leopold?

Adam Huggins 17:26

Aldo [bleep] Leopold, and so many other really important scientists of their era, which are names that I didn't even recognize and most people probably wouldn't. People like George Bird Grinnell and Gilbert Peterson. But, could you imagine hearing an essay from A Sand County Almanac read aloud for the first time, in confidence?

Fern Yip 17:45

So, why secret society? What do these men have to hide?

Adam Huggins 17:49

It's not so much what they had to hide, but what they had to lose.

[Classical music fades out, intense, foreboding music with a strong beat begins]

Adam Huggins 17:54

As scientists with positions of influence in governments or institutes--on both sides of the border--they felt they wouldn't be able to do their work and have any influence if they didn't appear to be completely..."objective". Major air quotes around that one.

Briony Penn 18:09

You know, scientists were bending over backwards to meet some kind of objectivity in the face of a political force, a populist, political force, that doesn't value objectivity, in fact.

Fern Yip 18:22

That sounds eerily familiar.

Adam Huggins 18:24

Yeah, this crazy double standard, where scientists are supposed to be objective, disinterested, and meanwhile, they're basically sitting ducks for political forces around them that are anything but.

Briony Penn 18:35

And always the power structure is that whoever wants to get resources to the market and objects to anybody standing in the way is going to try and discredit the scientists who are trying to provide sober thought about what that means-- whether it's extracting timber, extracting minerals or playing around with Mother Nature just one bit too much.

[Static, cuts to video clip]

Media Clip 19:00

[Donald Trump] You'd have to show me the scientists because they have a very big political agenda.

Media Clip 19:05

[Reporter] Canadian campaigners call it a quote, "War on Science", a slow and systematic unraveling of environmental and climate research budgets under the Conservative government, Stephen Harper.

[Static]

Adam Huggins 19:16

So basically, these men had to meet in secret to express their deep love of nature, and their spiritual connection in their writing, and their grief. Because they just couldn't do that out in the open. They couldn't provide their political enemies with any ammunition to somehow discredit them or push them aside. So, while Cowan was in many ways, the classical definition of a naturalist--in the tradition of Darwin and Aldo Leopold and John Muir-- he couldn't show it. And that's why the B was a complete secret until Briony happened upon that file just a few years ago.

Fern Yip 19:53

Wow. That's amazing how that story is reminiscent of what's happening today. 100 years later with the March for Science, and the muzzling of scientists.

Adam Huggins 20:04

Harper administration, the Trump administration.

Fern Yip 20:06

I'm not so sure, though, that this adherence to some sort of notion of objectivity is actually good strategy anymore.

Adam Huggins 20:13

Yeah. Which brings us to Cecil Paul.

[Music fades out. Bird sound begins in background]

Briony Penn 20:20

So that was one world that I was immersed in for three years. And then I went straight from that to working on the biography of a man called Cecil Paul, who is still alive. He's nearly 90, just a few years behind Ian. They all grew up through this turbulent 20th century.

Adam Huggins 20:39

While Ian was working within the academy and within government, and with his students and his TV series to effect change from inside the system, his contemporary, Cecil Paul, was very much on the outside. Cecil is the subject of Briony's latest biography, which is entitled, Stories From the Magic Canoe of Wa'xaid.

Fern Yip 20:58

Which I actually did read. Can I take this one?

Adam Huggins 21:01

Go right ahead.

Adam Huggins 21:01

All right, so, the first thing you notice about this book, when it's sitting next to the book about Cowan, is that...

[Pages flipping]

Adam Huggins 21:08

Uh, it's about a 10th of the size.

[Heavy thud, like a book dropping to the floor]

Fern Yip 21:11

An..it's full of stories that Briony has recorded, as Wa'xaid delivered them orally.

Adam Huggins 21:16

Right. Whereas The Real Thing is super detail-oriented, and has all of this documentation from Cowan's journals of people, and places, and organisms, and Cowan's life.

Fern Yip 21:26

Stories From the Magic Canoe... it's all oral history, kand it boils, the complication of a lifetime down to the elegant complexity of stories. Cecil Paul's story begins in the Kitlope.

[Waves crashing gently and birdsong]

Briony Penn 21:40

Cecil Paul was raised in the Kitlope, which is south and east of Kitimat, in British Columbia, in a very, very, very remote area. And he was Xenaksiala, a member of the Xenaksiala First Nation. And this is an area that is incredibly beautiful, high, mountainous, big raging rivers. It's the largest temperate rainforest that's unlogged on the planet. And this is the environment in which he was born, and he then was subjected to virtually every kind of form of colonization and cultural genocide, right? That entire nation went from, you know, thousands to 30 members. So, out of that tradition, he then went on to become a major leader in the environmental movement that was coming from an indigenous kind of worldview.

Fern Yip 22:43

There are so many incredible stories in the book from Cecil Paul's life, but one of the most remarkable is how his family managed to keep him out of residential schools for over a decade.

Briony Penn 22:54

He was lucky to have been hidden for 10 years, and he was raised by his grandfather, because his father had died of tuberculosis. He, his grandfather really was from a tradition that we can hardly even imagine now.

[Gentle, melancholy piano music]

Fern Yip 23:11

And this relationship is really critical, because eventually he is found and extracted from his community and taken to residential school, which really defines the next few decades of his life, where he works in extractive industry and struggles with alcohol and racism.

Adam Huggins 23:28

Which, which in his stories, he refers to as, as arrows, right?

Fern Yip 23:32

Yes. But he maintains this deep connection to the Kitlope, the place where he was born and where he was hidden from the state. And he tells this really poignant story about these survey markers he finds on ancient cedar trees near his birthplace, which, because he's worked in forestry, he knows means they're slated to be logged. And this starts him on this incredible journey back to his roots, and also towards leadership of a movement to protect the Kitlope, which he ultimately succeeds in doing, by getting enough people to board his magic canoe and paddle together.

Briony Penn 24:11

And Cecil Paul, everything in his life is metaphor. He used metaphor and uses metaphor in order to cope with all the, you know, as he calls him the arrows that have been thrown at him. But his most powerful metaphor, I think, is, is the magic canoe. So, his concept is that we're in trouble. And, and if you're a Xenaksiala person, you can get into trouble very quickly because you're in big country with big floods, big river systems, big avalanches, big landslides, big snowfall, big everything. Big trees, big ruts. You have to know, you have to be prepared for, for change, chaos, and big events. And so, their metaphor was that when when you're in trouble, you just get everybody in the canoe, everybody has a role, and then you paddle, and you paddle in the same direction.

[Sounds of water lapping on gunnels]

Briony Penn 25:05

And so, his book is called Stories From the Magic Canoe of Wa'xaid, because he feels that climate change is the biggest challenge now, and that we have all got to get into the canoe and we got to paddle in the same direction. And, and in that canoe, you can have very many roles. And it has roles like the [Xenaksiala word], which is this person that sits right up at the front and spots what's going on ahead, because sometimes there might be a hidden rock, sometimes there could be a little treacherous whirlpool, that [Xenaksiala word] is not the person that's paddling in the back. It's not the, you know, sort of more Western notion of a captain; it's the person that's sitting up front and calling treacherous things that are coming up ahead. And I'd say that that's the naturalist, now. That would have been the shaman then. It's that role of sitting up at the front and identifying problems coming up. And that's, that's the role that Cecil Paul has been doing, and that is the role that Ian McTaggart Cowan did. Ian McTaggart Cowan was calling climate change in 1951.

[Piano music intensifies]

Adam Huggins 26:18

Holy smokes.

Fern Yip 26:20

Yeah. And Cowan and Cecil Paul are in that canoe together, for a brief moment in time, when they try to prevent the construction of the first Kemano hydroelectric dam.

Briony Penn 26:31

Well, the two men joined over this issue, not, not physically, but they were both working on trying to stop this huge hydroelectric dam that went in in the early 1950s.

Media Clip 26:43

[Narrator] In 1952, the Kenney Dam was the largest sloping clay core rockfill dam in the world. A huge 230 kilometer long horseshoe-shaped reservoir was created, and a tunnel blasted through Mount Dubose to deliver water to a power generating station in Kemano, 80 kilometres from Canada. But the Kenney Dam meant flooding thousands of hectares of prime forest and agricultural land. The Cheslatta First Nation was given one week to move out and lost homes, livelihood, and their dead.

Briony Penn 27:16

This was, you know, billions of dollars at a time when you didn't have these kind of mega projects at that scale. It's probably one the largest projects in North America. And Ian McTaggart Cowan had tried to stop it through Western science. He was saying this is a huge project, it's going to have huge impacts on the salmon fisheries of not only the Fraser because of the Nechako, and then also on the other side with the Kemano River. Meanwhile, Cecil Paul was the one saying you can't bring in all these hydroelectric dams without having profound impacts on fish populations, because he would watch things like the little Eulachon fish, which are these little--sometimes they're called candle fish because they're full of omega three oils-- and they were the staple of his, his diet, and the in the Xenaksialan diet. And today we're always talking about omega three oils, you know, as if we've invented this notion Well, no. You know, these, these little fish have been the source of wealth and health for thousands of years. So, here are these two men both fighting this issue unbeknownst to one another. And coming from very, very, very different perspectives. Ian had access to every...every door would open for him because he was a very esteemed scientist. He brought the data, he could walk into politicians offices and, and they would listen to him somewhat, and they tried to moderate, you know, what they were doing. Meanwhile, you have a person that has been sent to residential school and not even learned how to read and write, but he's got the benefit of having lived this environment and survived on the oils of the Eulachon, arguing against it from a very heartfelt way. And that's how I first met him--this is, Cecil Paul--was he had come down to Victoria to give a talk about the impact of the Kemano project on his territory. It was a hereditary chief of that particular watershed, the Kemano. So, both stories, I realized, that I got--I sort of went into the lives of these men and there were so many similarities.

[Piano music fades out]

[Sound of water on gunnels of boat]

Briony Penn 29:31

I mean, there's nothing similar in terms of their upbringing, their privilege, their, their access to power bases, their education. Nothing. One is, you know, one of the most celebrated scientists in Canada and the other is doesn't even have a grade two education. Yet they were both amazing naturalists.

[Calm, buzzing background music]

Briony Penn 29:57

I think there was a whole lot of things that really, it raised for me about the role of naturalists. That being a naturalist is not, not confined to one culture. It's a human condition--these people that observe and, and inform, and educate, and have very high coordination of heart and mind.

Adam Huggins 30:24

That's a, that's a beautiful observation that she makes, that the tradition of the naturalist in some ways, eclipses, culture and time, and history.

Fern Yip 30:34

It is. And while Cowan and Cecil Paul weren't able to prevent the construction of the first Kemano Dam, Cecil Paul was successful in preventing the second.

Adam Huggins 30:43

I actually recently visited the Nechako Reservoir, which is created by the Kemano Dam that was built in the 50s. And it just so happens to be flooding 910 square kilometers of the critical winter habitat of the Tweedsmuir heard of Mountain Caribou. In addition to all the downstream effects that it has on fish and other species, of course.

Fern Yip 31:06

Another dam tragedy.

Adam Huggins 31:09

[Laughs] Oh my god, and you were telling me that we had a lot of bad puns on the podcast.

Fern Yip 31:15

[Laughs] Don't put that one in.

Adam Huggins 31:16

[Laughs] That one is all on you, Fern.

Adam Huggins 31:21

So, um, is that it? Are we done here?

Fern Yip 31:24

No, we're not actually done here.

Adam Huggins 31:26

No?

Fern Yip 31:27

We're not done with this topic. I do really appreciate the beautiful and elegant illustration that Briony provides in all of her research of those two men and what a naturalist is. But there's more to it than that. There's more to being a naturalist than just being the spotter at the front of the canoe.

[Upbeat music intensifies and ends]

[Xylophone descends]

Adam Huggins 32:19

All right, so um, Fern, who, who are you?

Fern Yip 32:23

Oh, I'm...a bipedal from the planet Earth [laughs].

Adam Huggins 32:28

[Laughs] Why, why uhh...why are you here in this room talking to me?

Fern Yip 32:35

Well, I live next door, so I, you know, live a paddle away.

Adam Huggins 32:38

You're on the next island over [laughs].

Fern Yip 32:38

[Laughs] That's right. The next island over.

Adam Huggins 32:42

Which is where Briony lives as well, Salt Spring Island.

Fern Yip 32:44

It is. We're all connected through the Salish Seas. I'm...what I've been doing for the last couple years is really trying to get to the bottom of a super simple question, which is how do we reconnect with people with nature? We come from inheriting a human story of disconnection, that of being disconnected from ourselves, other people like community, and the greater world of the earth. Reconnection work is to change that story to one where we are re-woven into the web of life.

Adam Huggins 33:26

It's interesting that you say...story. What did you feel was missing from the stories that Briony was telling? What do you want to add to that definition of the naturalist?

Fern Yip 33:38

Briony uses two examples of what I would consider outstanding humans. People, you know, Ian and Cecil Paul lived larger than life lives, and they left impacts that were equal to that too. But the story of a naturalist, or being a naturalist doesn't just belong to the exceptional. It's a story that belongs to everyone. And I wanted to dive deeper into that idea and see if it had any substance. So, I have been interviewing some people who are deeply involved with nature connection work, and who, in a way, are training the next generation of naturalists.

Adam Huggins 34:29

Yeah, and it's not just happening in the academy or even necessarily on the trap line. It's, it's happening in this whole new context.

Fern Yip 34:37

Definitely. I mean, it's happening up in the trees.

Wolf Kid #1 34:41

Are you interviewing people in a tree?

Fern Yip 34:43

I am interviewing people in a tree.

Wolf Kid #2 34:45

Rather high, too.

Fern Yip 34:46

Yeah, it's a high interview.

Wolf Kid #1 34:49

It is a high interview.

Wolf Kid #2 34:50

You know, the expression you have friends in high places? Well, you have interviews, in high places.

Fern Yip 34:55

[Laughs] I like interviews in high places.

Wolf Kid #2 34:57

[Laughs]

Adam Huggins 34:59

Fern, you've been spending some time with some little...proto people. With some, with some, um, young human, pre-humans.

Fern Yip 35:07

[Laughs] Adam, I don't--

Adam Huggins 35:07

Larval humans?

Fern Yip 35:09

[Laughs] They are still fully human. They're just a different size, and maybe a little bit different stage of development. But yes, I, I myself work with kids outside, and I was also able to interview quite a few kids who are engaging with the natural world in a really significant way.

Fern Yip 35:36

Yeah, introduce yourself, go ahead.

Sahara 35:38

I'm Sahara. I've been at WOLF [mumbles], I think this is my...third year. And I uhhh...I'm 13, almost, in two weeks.

Matilda 35:54

I'm Matilda, um, and then I've been at WOLF forlike, eight months. Nine months-ish? [laughs] And um, I'm 12.

Fern Yip 36:04

They're all part of this program called WOLF that's run by Wisdom of the Earth, a school on Salt Spring Island.

Fern Yip 36:11

What are we in right now?

Matilda 36:12

A tree.

Sahara 36:13

A giant cedar tree.

Fern Yip 36:15

That's pretty incredible. We're like...

Matilda 36:17

Yeah, I love just like, climbing trees

Fern Yip 36:18

...15 meters off the ground right now

Matilda 36:19

and just like looking up at like bridges.

Fern Yip 36:22

You both seem pretty comfortable in this tree.

Matilda 36:25

Yeah.

Fern Yip 36:26

And just being outside. Was that always the case? For either of you?

Matilda 36:31

I didn't climb a tree until like, I know maybe like nine months ago [laughs].

Sahara 36:38

That's so crazy.

Adam Huggins 36:39

And, you talked about, you talk about a "sit spot", a "sit spot" too, as being this important practice, and a lot of the kids mentioned the sit spot.

Fern Yip 36:47

Right? Yeah.

Adam Huggins 36:48

What is what is a sit spot?

[Uplifting music]

Fern Yip 36:50

The sit spot is a routine that allows people to connect with place on a, in a deep way.

Fern Yip 36:59

What does this sit spot mean to either of you?

Matilda 37:02

It's sort of, I wouldn't call it like meditation, but it's like, it's sort of, it's like just sitting and like stepping back, I guess from your life and just like observing everything else's life.

[Bird calls in background]

Matilda 37:14

Which is pretty cool, and we usually do it for like maybe 15 minutes at WOLF, but like I've heard of people who do it for like seven hours [laughs].

Fern Yip 37:21

Is it the same place all the time? Is this place outside?

Matilda 37:25

Um, yeah, it's outside. Um, I don't know. A lot of people's sit spots are in a tree, so that's pretty cool. Mine is on the ground but near a tree, so that's pretty cool. And um, we really get to like, know that place, and um, like as the year progresses, you'll see that like, the animals they're like get used to you, and so they you know, like I saw a woodpecker. I was sitting at my sit spot. And a woodpecker just sort of like came up like super close to my face and just started like moving up a tree. I was like, whoa, that's so cool. So yeah.

Sahara 38:00

One time, I think this was two years ago, my first year at WOLF, a Brown Creeper landed on my arm for just a second, but it was still really cool.

Adam Huggins 38:12

So in your conversations with these with these kids, like, what does it mean, what does it mean to them to be a naturalist? Why are they there? Why are they doing what they're doing? How do they value what they're learning?

Fern Yip 38:23

Well, it's best to ask the kids those questions.

Fern Yip 38:26

Do you feel like you notice more things out, now when you're outside now?

Sahara 38:34

Oh, yeah, definitely. Yeah. 100%. Totally. Yeah.

Fern Yip 38:39

What's the difference? What's changed?

Sahara 38:42

I mean, I guess I can I know, I have so much more knowledge. Like, when I hear a bird, I'm like, "Oh, it's this bird". Or either I say that, or I'm like, "I want to know what this bird is". But before I'd just be like, Oh, it's a bird. Okay, that's cool. And like the trees and everything is like that. And plants, and...

Fern Yip 39:05

Do your friends outside of WOLF have that understanding? Or do you notice a difference? If you have, hanging out with friends outside of WOLF?

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 39:15

Yeah, I think I can tell that they're just like not as connected, and have not as much knowledge about that kind of thing. And just like hanging out with them I outside can really bring that out, and I can see that for sure.

Fern Yip 39:32

Do you think this kind of knowledge is important, even?

Sahara 39:35

Yeah, I think so, yeah.

Fern Yip 39:39

Why is that?

Sahara 39:42

Um, I don't know. I guess because it's to be able to like help yourself and if something happens, like...

Matilda 39:52

I don't know just like, to be able to connect with the natural world is really cool and like, you know, to be able to, like Sahara said, be like, "Oh, this tree is Red Cedar and that trees a Doug fir". And like, you know, "Oh that bird's, I don't know, a Golden-crowned Kinglet or whatever" is pretty cool. Like, I don't know, a year ago I'd be walking through a forest and I would just be like, oh, trees and birds.

[Sounds of kids playing in background]

Matilda 40:22

And now, I like, there's so much diversity of like, you know, different trees and different birds and like all the life in a forest is just mind blowing.

[Uplifting music continues]

Adam Huggins 40:47

These kids had such interesting answers to these questions. On the other hand, though, it's really hard to articulate sometimes. I think that's one of the things about naturalism. It's hard to articulate to people who don't understand it, or who haven't been raised like that, the importance of it. And then it's also sometimes hard to articulate even amongst ourselves like, like I call myself a naturalist before I call myself anything else. I don't necessarily know how to explain why it just doesn't feel right to say biologist or artist or. Naturalist fits. But when you ask these kids, a lot of the times they're like, well, it's really nice to know the names of the birds right? And that's maybe that's like phase one naturalist is like birds are like the gateway drug for naturalism.

Fern Yip 41:32

I think that would actually be very true. Birds are [laughs] the gateway drug to naturalism.

Wolf Kid #3 (Maya) 41:37

Um, I like how unique their songs are, and how, just like the different colors and their feathers and whatever.

Fern Yip 41:46

The term naturalist doesn't--is unfamiliar to them.

Adam Huggins 41:51

It doesn't necessarily resonate with them.

Fern Yip 41:52

Well, yeah. The kids--they don't really know what that term means.

Fern Yip 41:56

What does it mean to be a naturalist?

Wolf Kid #3 (Maya) 41:59

I don't know like...[laughs sheepishly].

Fern Yip 42:02

Do you see yourself as someone who might be a naturalist?

Wolf Kid #3 (Maya) 42:06

No.

Fern Yip 42:06

Does that term even mean anything to you? Naturalist?

Wolf Kid #3 (Maya) 42:09

Not really.

Fern Yip 42:09

Not really? Hm.

Fern Yip 42:10

But if you ask them, the things that they're learning and what they're excited about learning, suddenly they're telling you about all the different things that you can use with seaweed.

[Kids talking excitedly]

Fern Yip 42:21

Okay, what do you have? Can you...

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 42:23

I believe we have bleached [mumbles].. or some Turkish towel.

Wolf Kid #4 42:27

[Kid in background] Why is this like, so weird?

Fern Yip 42:28

What are those?

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 42:29

Seaweeds.

Fern Yip 42:31

Oh okay.

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 42:31

The Turkish towel, it like actually looks like a cow skin because some of it's bleached and some of it isn't.

Fern Yip 42:36

What do you know about these seaweeds?

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 42:38

Not much.

Fern Yip 42:39

Oh, yeah?

Wolf Kid #4 42:40

[Interjecting] All I know is that...

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 42:41

I, I'm no..seaweed-ologist but.

Wolf Kid #4 42:43

All I know is that the Turkish towel...

Fern Yip 42:45

Can you eat them?

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 42:46

Yeah.

Fern Yip 42:46

Oh you just ate some, all of you are eating some right now.

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 42:48

Yep. Yeah it's, it's all seaweeds in BC, I believe are edible.

Wolf Kid #4 42:52

And the Turkish towel, um, yeah, you can use it as like a towel. You can use it as like...

Wolf Kid #5 42:56

[In background] It kinda feels weird [laughs]

Wolf Kid #4 42:57

It's really spiky, and it feels nice. If you....

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 43:01

Yeah, yeah, it's, it's, it's basically a towel. Yeah. You could literally use it as a towel.

Wolf Kid #4 43:05

It's a spiky towel.

Wolf Kid #5 43:06

Except it's wet.

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 43:07

If you dried it.

Fern Yip 43:09

Why did you, why did you collect these ones?

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 43:11

Cause we're gonna like dry them and eat them.

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 43:12

And because we're doing a survival trip in the [?] for our year-end,

Wolf Kid #4 43:12

Cause they're yummy.

Wolf Kid #4 43:13

See this?

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 43:16

For our year-end trips, we're gonna use it.

Fern Yip 43:18

Can you just say your name and how old you are?

Wolf Kid #2 (Isaac) 43:21

Isaac and I'm age 10. As of yesterday.

Fern Yip 43:24

They have some intimate knowledge of land that they've been observing, which based on I think, what we explored with Briony, that would qualify them as some kind of naturalist.

[Kids laughing and mumbling]

Music Circle 43:44

[lyrics] Who's got something to say? Tell me about it. About our day. Ah no, please no. [laughs]

[Groovy beat begins]

Fern Yip 44:38

I thought that was a pretty groovy rhythm.

Fern Yip 44:41

So, yeah whenever, whenever you want to introduce yourself.

Arnaud Gagne 44:46

Hi, I'm Arnaud Gagne, and I'm the core instructor for the Wisdom of the Earth immersion program, for adults: a nine month, nine month journey into deep nature connection, mentoring, and culture repair.

Matt McKinney 45:02

Hi, my name is Matt McKinney. I'm one of the mentors at Wisdom of the Earth School. I've been doing [eight shields?] deep nature connection mentoring for about a decade.

Jean-Claude Catry 45:12

[With a French accent] My name is Jean-Claude Catry, and I come from France, and basically, I'm a village builder. I'm the director of Wisdom of Earth Wildernees School that exists for the last 15 years, I suppose? 16 years? And what motivated me is uh...the loss my village when I was seven years old to move to a city and that trauma is informing what I'm doing now, because basically what I'm doing is to regenerate village [chuckles]. And so we started that school, and we started to work with kids first, and and soon enough, we understood that if we wanted to bring kids for a journey of deep nature connection, we had to work with the parents with them. And from there, yeah now this program's in our school for uhh..her old age [laughs].

Fern Yip 46:08

And in your experience, what does it mean to be a naturalist?

Jean-Claude Catry 46:13

I felt for me there's uhh...a problem inherent to the word is that the word naturalist implies a specialization in a bigger context of a society where other people are not naturalists. So, my, my question is what other people are relating to if they are not naturalists. Like in indigenous culture, everybody has to be a naturalist. You have to know everything about the world, to know themself and to be able just to survive. And so the naturalist concept is born out of a society that lost contact with nature. And we created a specialty to, to remind us of that connection.

Arnaud Gagne 46:55

I like to take it to some of my, my main teachers on this journey, the most, more recent part of this journey have been of the Lakota people. And there's a word which is [speaking in Lakota], and it translates as "the common man". To understand what it really means, you think about the common person 1000 years ago, rather than the common person today on, on a city street. So that common person is connected to all things. They're connected to their family, to their ancestors, to all the different plants, and animals, and birds, and they're connected to hundreds of species that they interact with and not just on a knowing their name and even their habitats, but they have a really close relationship of everyday interaction with these, these more-than-human beings. And so, the other translation is "the real people", or which I would interpret as "the natural people".

[Bird calls in background]

Arnaud Gagne 48:09

So the people that are who they are because they've built all these relationships with the natural world.

Matt McKinney 48:17

Yeah, in the context of the work that I do, there's an idea that everyone is a naturalist and should be a naturalist. And nature is a pattern language. So, that's kind of the primary way that our, our brains are formed, or used to be formed. Now, there's lots of other systems in place that, you know, our brains form on, on different systems. So, a lot of what we're doing is facilitating structures through which that language of nature can be more primary in the development of young people, and then for adults, how to repattern our brains, on natural systems. So being a naturalist is kind of just about being human.

[Music]

Adam Huggins 49:18

I could totally see why these kids love being out there and doing what they do. I wish I had that as a kid.

Jean-Claude Catry 49:25

And so, when a child that is five years old, already have lot of things missing. So I think it's true for all the kids that I've been mentoring, at one point they come to what we call the wall of grief. It's like now we have a choice. Either we keep going in reconnection, and we have to transform that and being willing to feel it, or we are going to avoid it, and in some way, the whole modern society, the whole idea of progress, is the strategy to avoid the grief. And so we create a solution to problem we imagine we created. And we don't need to fix it. We just need to fully grieve it and to be able to transform it. Because beyond that wound, there's a tremendous gift that can be offered to the world.

Adam Huggins 50:15

I wish that I was put in those kinds of environments and given those kinds of teachings and had that less mediated relationship with nature, and I certainly want that if I ever have children.

[Beat picks up]

[Crickets begin]

Adam Huggins 50:27

But at the same time, I think, you know, playing devil's advocate it's like, when we think about developing young naturalists now, is it just something that those of us who have the privilege to do so can engage in because it's good for, it's good for us, it makes us feel good, it brings us closer to the natural world? But what, like what larger societal good does it do?

Fern Yip 50:56

These nature studies aren't just about being able to name every single bird or to know the various medicinal uses of plants. The utilitarian aspects of this knowledge are important. But what is perhaps even more important is how our study of the natural world informs our human development, how it creates a different kind of human. And that's why when children...

[Owl hooting]

Fern Yip 51:34

..are guided by the natural world at an early age, through different stages of development in their lifetime, it's going to help them become fully alive people.

Adam Huggins 51:48

I think, I think you cut right to the, to the heart of it--that there may be utilitarian aspects to this. Maybe in a pinch if you don't, [chuckles] you know, if you need to light a fire you know how, and maybe in a pinch, you know where to find food where other people won't. Or you know how to conduct yourself, right, in the more than human world, right? And those are benefits, tangible benefits, both to yourself and potentially to society. But that's not necessarily the point. The point is, what kind of people we're making. What kind of people were making out of the proto, larval humans that I was talking about earlier. I think my biggest concern and, you know, from the outside--and even myself sometimes--I think is this just a lifestyle? Is this just one of many modern lifestyles that you can have that is more about your personal identity, and who you are, how you are different from other people, than it is about actually getting us as a species to where we need to be to, to survive and thrive, right? There's always that risk, or that fear, for me, that oh, this is just another one of so many lifestyles that you can choose to kind of, you know, accessorize yourself as a human being, right?

Fern Yip 52:59

And yet, I think that, at the core of all these like, little lifestyles that you can try on, when you explore them, there's an inner transformation that's very deep that can happen. That it is no longer a lifestyle, but becomes a life way. And a life way that can impact the way we humans are in the future. That's when it, that's when it begins to actually have real substance and meaning.

Adam Huggins 53:31

Can you give me an example?

[Music]

Matt McKinney 53:33

Okay, well, like last year, I worked this program in Anacortes. And I remember the first, the first week, all of these kids were like, afraid to sit on the ground, you know? Like, like, they had to, like get their coats off and like wrap them up and like I had to kind of just like, play games with them and, and, and kind of joke and like, continually invite them to sit on the ground, let them know it was fine to sit on the ground, and they don't have to worry about getting dirty. I think by the fifth or sixth session, which was like one day a month, just one Friday, a month. By the sixth Friday, we were, you know, like all covered in mud, like racing down the trail to get back to the parking lot where the parents are going to pick them up. And there was this rabbit that had it's like limbs--it was like quartered by some, like a coyote or a fox or something. But it's fur was just strewn across the trail and like the body parts were like, strewn on each side of the trail in the bushes, and the kids were like ravenously looking for all the body parts and I'm like, like trying to usher them down the trail like, come on, you know, like, we got to get back because like, we have five minutes to get, you know, whatever, couple kilometers down this trail and the kids are just like, beside themselves preoccupied looking for dead animal parts to try to put this story together of who killed this rabbit, you know? And so that's a very, those are very different...

Adam Huggins 55:18

Protohumans? Larval, very different larval humans?

Fern Yip 55:23

[Laughs] Don't put that in there. That's a terrible metaphor. [Laughs]

Adam Huggins 55:27

[Laughs] I actually don't think it's a terrible metaphor at all, like, going from the, you know the caterpillar to the...it's a lepidopteran metaphor that I ike. It's very much in keeping with the naturalist.

Fern Yip 55:42

Oh yeah...

[Cheerful music]

Adam Huggins 55:47

So...what now?

Briony Penn 55:48

Well, I, I asked this question of both men that I was interviewing. The question of what to do. I remember asking Ian this and he said "Well, I've always been an intentional optimist, in that I've set my intentions as being optimistic because what else can we do?" So, he always felt that there was three things that you needed to do. One was to mentor the young. The other was to share information. But that was for him, it was so important, was the sharing of knowledge. And, and the other one was to spend time, was to spend time out there. Spend time, enjoy it, share your knowledge, and mentor young people.

Adam Huggins 56:38

Yeah, but how?

Briony Penn 56:40

He knew. He would say "When I was teaching, if I started with, I don't know, Copepods, none of my class would be with me. I'd see all these boree eyes and you know, kind of shifting kids", because he taught in a first-year zoology. So he said, "I always started with humans, and I always started with sex. And I had them then, they were just like gripped". [Laughs] "And then, then I'd finish with the protozoa".

[Buzzy, meditative music]

Briony Penn 57:17

And I think both of them would say that, that the secret to both of them, because they were both great communicators, is start where people are, and then take them on the journey with you.

Adam Huggins 57:32

Well, what do you say, Fern? Shall we step into the Magic Canoe and be a part of a better story?

Fern Yip 57:39

I'd like to be part of a better story [laughs].

Adam Huggins 57:40

[Groans] Me too. Oh, let's be part of a better story together [laughs].

Adam Huggins 58:02

Thanks for listening. We highly recommend you read one of Briony's books. A Year on the Wild Side, The Real Thing, or Stories From the Magic Canoe of Wa'xaid. You can find them all at brionypenn.com. Also, for more about The B, check out "The Bison and the B" from CBC ideas. And if you'd like to learn more about the Wisdom of the Earth School, check them out at wisdomoftheearth.ca. This episode of Future Ecologies was produced by myself, Adam Huggins, with help from Mendel Skulski and Fern Yip. We'll be back next month, on the second Wednesday. Tell your close friends or anyone who you think might like what we do. Subscribe, rate, and review the show wherever podcasts can be found. It really helps us get the word out.

Fern Yip 58:52

In this episode you heard Briony Penn, Arnaud Gagne, Matt McKinney, Jean-Claude Catry, and WOLF Kids: Matilda, Sahara, Isaac, and Maya.

Adam Huggins 59:03

Special thanks to Briony Penn, Simone Miller, Tori Elliot at Touchwood Editions, the entire team at Wisdom of the Earth School, [Elena ?], The Access to Media Education Society, and the WOLF kids.

Fern Yip 59:18

Music In this episode was produced by kmathz, VALSI, Luke Garrigus, Claude Debussy, Leave, and Sunfish Moon Light.

Adam Huggins 59:26

This has been an independent production of Future Ecologies. Our second season is supported by our generous patrons. If you'd like to help us make the show, you can support us on Patreon. Patrons get cool swag and an exclusive bonus mini episode every month. This season, Mendel is taking us on a tour of kingdom fungi. To support us and get access head to patreon.com/futureecologies.

Fern Yip 59:51

You can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and iNaturalist. The handle is always Future Ecologies. You can find a full list of musical credits, show notes, and links on our website: futureecologies.net.

Adam Huggins 1:00:04

Thanks again for listening.

Introductory Voiceover 1:00:15

[Whispers] You are now listening to Future Ecologies ASMR.

[Music fades out]

[Popping sounds]

Adam Huggins 1:00:32

Ah, gooey.

Mendel Skulski 1:00:36

It's like a leathery grape.

Adam Huggins 1:00:38

It is like a leathery grape. I'm gonna eat one.

[Exaggerated slurping sounds]

Adam Huggins 1:00:48

[With food in his mouth] Mmm, it's got a big pit.

Mendel Skulski 1:00:48

Okay.

Mendel Skulski 1:00:58

Ah these are funny.

Adam Huggins 1:00:59

I could do this all afternoon.

Mendel Skulski 1:01:00

I want another. Ahh it's too squishy.

Adam Huggins 1:01:07

Do you know anything about these?

Mendel Skulski 1:01:09

[Laughs] I thought we weren't being educational. I wonder if the point of fruit is to get animals more fascinated by seeds.

Adam Huggins 1:01:20

If there is a point of fruit, that, that, that could be said to be the core of it. The kernel. The pit.

Mendel Skulski 1:01:29

[Laughs] Mmhmm.

Adam Huggins 1:01:35

That's my favorite thing about fruit. It...[takes a bite] there doesn't have to be a point.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai and edited by Amelia Cole