Mt. Assiniboine and Magog Lake: A. O. Wheeler, 1913 & Mary Sanseverino, 2017

Arthur Wheeler and assistant (1915)

Jeanine Rhemtulla on an early repeat photo

The field team preparing for their day

Zac Robinson on the Mount Logan Ice Expedition 2020/2021

Eric Higgs lining up a repeat photo

Summary

From a distance, mountain landscapes may appear timeless and immutable. Take a closer look, however, and montane ecologies reveal themselves to be laboratories of radical transformation: rocks weather and fall; ecosystems burst into life for brief intervals; tree-lines shift; and wildfires rage. Even the very peaks themselves inch inexorably upwards or downwards with the flow of time.

Amidst all the constant, unyielding change that animates the Earth's high places, people have long sought a vantage from which to survey this shifting terrain. Who can resist the romance of a breathtaking, mountaintop view? Or then to imagine what generations past might have seen from the same spot?

In the mid 1990s, a small group of scientists in western Canada grew dissatisfied with mere imagining — they wanted to see that change for themselves. And in a forgotten corner of a national archive, they found some very heavy boxes that held a rare promise: an opportunity to look back in time at a landscape scale.

Learn more about the Mountain Legacy Project: mountainlegacy.ca

Explore all the photos and data: explore.mountainlegacy.ca

One of Arthur Wheeler’s large cairns

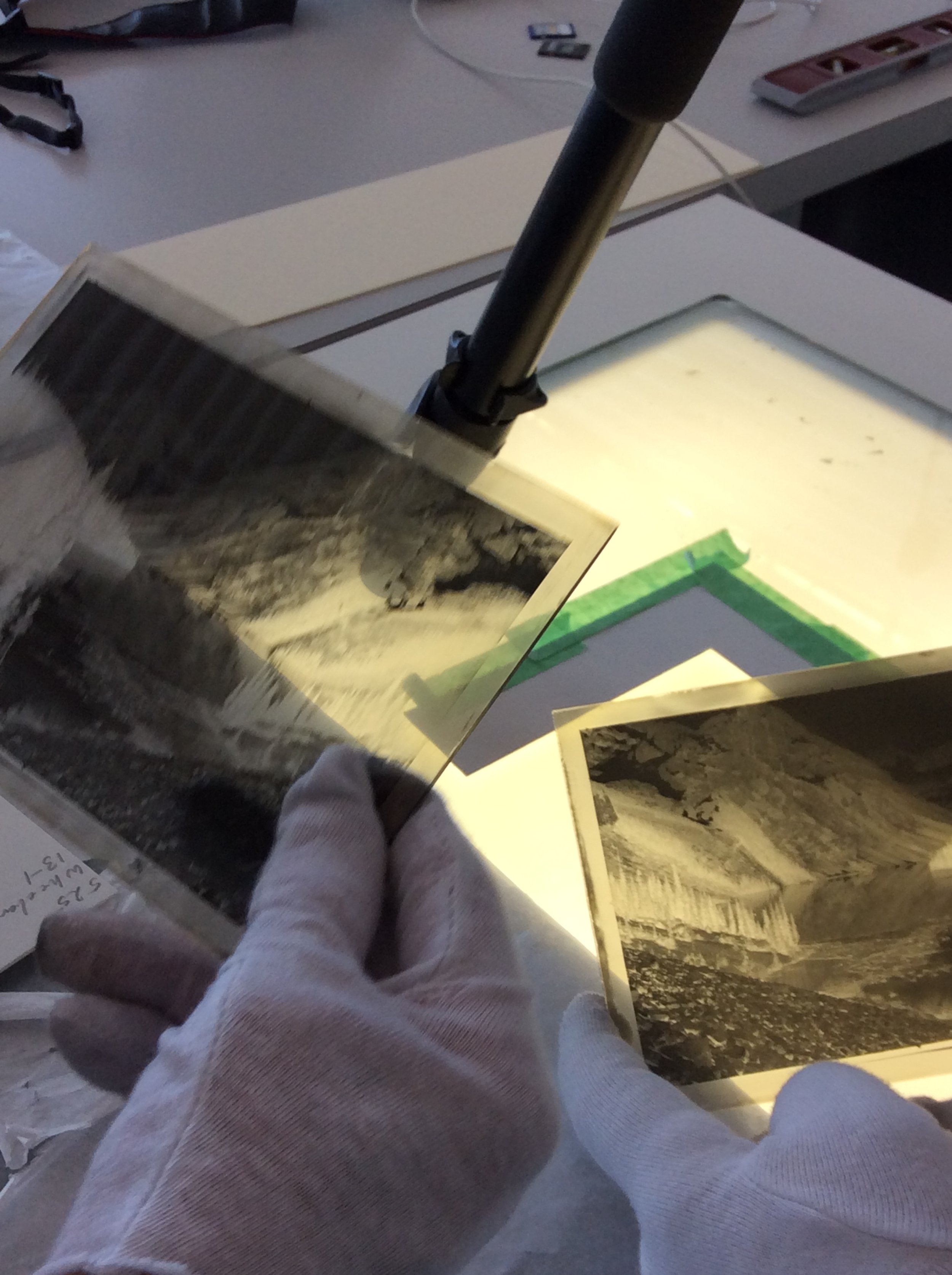

Digitizing glass plate negatives at the National Archives of Canada

Julie, Sandra, and Kristen line up a shot

Show Notes

This episode was produced by Mendel Skulski and Adam Huggins, with help from Eric Higgs, and features the voices of Jeanine Rhemtulla, Eric Higgs, Mary Sanseverino, Brian Starzomski, Bill Snow, Sandra Frey, Julie Fortin, Jenna Falk, Alina Fisher, Andrew Trant, Kristen Walsh, Jill Delaney, and Rob Watt.

Music by Thumbug, Shadow Acid, Erik Tuttle, Sage Palm, and Sunfish Moon Light

From Eric:

There are many voices associated with the Mountain Legacy Project, and only a few are represented in this episode. First, to the gifted field team members, who since 1998 greeted so many mountains and learned to love delicate camera equipment. Dedicated volunteers such as Ian MacLaren, Rob Watt, Rick Arthur and Sandy Campbell turned a research notion into a sprawling project. Heroes within institutions such as the University of Victoria, Parks Canada, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry—Jonathan Bengston, Shahira Khair, Jeff Albert, Rick Kubian, Mike Eder, Kim Pearson, Bruce Mayer and many others—ensured the flow of in-kind support and funding. Funding agencies, such as SSHRC and fRI Research, supported innovation. Colleagues and students near and far have continuously stirred new ideas. All of this work is made possible by two professionally introverted groups: archivists and software specialists. Thank you to Pascal LeBlond, Jill Delaney and the digitization team at Library and Archives Canada, and software whizzes Chris Gat, Spencer Rose and Mike Whitney. Might the most enduring legacy of our work be the transfiguration of colonial materials for support of Indigenous resurgence and reconciliation? I hope so, and am grateful for colleagues and advisors including Sarah Hunt, Darcy Mathews, Ry Moran, Craig Richards, Bill Snow and others for showing the way, such as the Canadian Mountain Network, SSHRC and fRI Research.

Funding for this episode of Future Ecologies was granted through the University of Victoria’s Pathways to Impact fund.

✨ Future Ecologies is an independent production, and is supported by our community of listeners on Patreon. You can join them for as little as a dollar each month — at patreon.com/futureecologies 🌱

Additional Credits

This episode includes audio recorded by oniwe, gadzooks, Benboncan, TheSoundcatcher, davidbain, felix.blume, eliasheuninck, Hitrison, filmmt, unfa, Redder01, richardemoore, 13GPanska_Gorbusinova_Anna, KenRT, petebuchwald, weaveofkev, beerbelly38, tim.kahn, kantoesploras, shatterstars, JBP, Ruben_Uitenweerde, JavierSerrat, andersmmg, Nivatius, shaunhillyard, BM007, Nox_Sound, EminYILDIRIM, yfjesse, Jorgesbcomposer, f-idam, TCduP66, accessed through the Freesound Project, and protected by Creative Commons attribution licenses.

CITATIONS

Beller, E., McClenachan, L., Trant, A., Sanderson, E.W., Rhemtulla, J., Guerrini, A., Grossinger, R. and Higgs, E. (2017) Toward principles of historical ecology. American Journal of Botany, 104: 645-648. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1700070

Delaney, J. (2008) “An Inconvenient Truth? Scientific Photography and Archival Ambivalence”. Archivaria, 65(1), 75-95. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13169.

Fortin, J, Fisher, J., Rhemtulla, J., and Higgs, E. (2019) Estimates of landscape composition from terrestrial oblique photographs suggest homogenization of Rocky Mountain landscapes over the last century. Remote Sens Ecol Conserv, 5, 224-236. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.100

Higgs, E. (2003) Chapter 4, “Historicity and Reference in Ecological Restoration” in Nature By Design: People, Natural Process and Ecological Restoration. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

MacLaren, I., Zezulka-Mailloux, G., and Higgs, E. (2005) Mapper of Mountains: M.P. Bridgland in the Canadian Rockies, 1902-1930. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

McCaffrey, D., and Hopkinson, C. (2017) Assessing Fractional Cover in the Alpine Treeline Ecotone Using the WSL Monoplotting Tool and Airborne Lidar, Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 43(5), 504-512, DOI: 10.1080/07038992.2017.1384309

McCaffrey, D., and Hopkinson, C. (2020) Repeat Oblique Photography Shows Terrain and Fire Exposure Controls on Century-Scale Canopy Cover Change in the Alpine Treeline Ecotone. Remote Sensing, 12,1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12101569

Rhemtulla, J., Hall, R., Higgs, E., and Macdonald, S. (2002) Eighty years of change: vegetation in the montane ecoregion of Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 32(11): 2010-2021. https://doi.org/10.1139/x02-112

Sanseverino, M., Whitney, M., and Higgs, E. (2016) Exploring Landscape Change in Mountain Environments With the Mountain Legacy Online Image Analysis Toolkit, Mountain Research and Development, 36(4), 407-416. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-16-00038.1

Stockdale, C., Bozzini, C., Macdonald, S., and Higgs, E. (2015) Extracting ecological information from oblique angle terrestrial landscape photographs: Performance evaluation of the WSL Monoplotting Tool, Applied Geography, 63, 315-325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.07.012

Trant, A., Higgs, E., and Starzomski, B. (2020) A century of high elevation ecosystem change in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Sci Rep 10, 9698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66277-2

You can subscribe to and download Future Ecologies wherever you find podcasts - please share, rate, and review us. We’re also on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and iNaturalist.

If you like what we do, and you want to help keep it ad-free, please consider supporting us on Patreon. Pay-what-you-can (as little as $1/month) to get access to bonus monthly mini-episodes, stickers, patches, a community Discord chat server, and more.

Future Ecologies is recorded and produced on the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the WSÁNEĆ, Penelakut, Hwlitsum, and Lelum Sar Augh Ta Naogh, and other Hul'qumi'num speaking peoples, otherwise known as Galiano Island, British columbia, as well as the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the Musqueam (xwməθkwəy̓əm) Squamish (Skwxwú7mesh), and Tsleil-Waututh (Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh) Nations - otherwise known as Vancouver, British Columbia.

Transcription

Introduction Voiceover 00:00

You are listening to Season Four of Future Ecologies.

Brian Starzomski 00:06

Mountains are very special places, no matter how you look at them. Whether it's recreation, or its biodiversity, or its human geography and human diversity, they're... they're absolutely beautiful, wonderful places.

Andrew Trant 00:20

There's a world that's compressed along a gradient that is tangible. So you can you can see it, feel it — you can walk from a forest and be in the alpine tundra in two hours.

Brian Starzomski 00:32

You know, you get isolation plus time. You have places that are hard to get to, and they're hard to get to for a long period of time. And it leads to diversity rising in those situations. And so mountains are always really exciting.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 00:44

Everyone who's ever moved through a mountainous landscape, like you know that it's like, it matters which direction you go, and you pick carefully the way that you move based on the topography of that landscape. And that's the same for every other creature that's moving — or every other biological or abiological process: wind, water, pathogens. And so those processes shape the change that we see: the gradients across those landscapes.

Brian Starzomski 01:07

So even just over small little bits of space (like meters, we're not talking kilometers), you can have radically different climate conditions and totally different species in those places.

Andrew Trant 01:18

At every level, at every elevation, it's a completely different system. So it's a connected system, but you find a different assemblage of plants and animals and all kinds of other things. And it's all... it's all very immediate.

Brian Starzomski 01:32

Because mountains are so difficult to move around in, they're often very under surveyed. Actually it turns out that we think we know lots about biodiversity, but if you go there at different times than when other people have visited a site, or you go to a place that people don't get to very often, you'll almost always find something new.

Sandra Fray 01:49

Something about being in the mountains, and just the vastness of those landscapes, and the hazards you sometimes see and experience, the friendships that are forged in those environments feel like they can weather a lot.

Mary Sanseverino 02:02

Yes, I always like to say: if you're lucky enough to be in the mountains, you're lucky enough.

Mendel Skulski 02:10

Hey, I'm Mendel.

Adam Huggins 02:11

I'm Adam. And it's no secret that we here at Future Ecologies have an abiding love for the high country. Every year. I wait with mounting anticipation for that brief window, just a few months really, when the snow recedes and all of the alpine ecosystems just burst into life. In some ways, it's what I live for. It's a call that I find completely irresistible.

Mendel Skulski 02:38

For many of us, mountains are little more than a backdrop for the rest of our lives, lived here on the flatland. For some though, they can be an intoxicating invitation to explore, discover, and self realize. And for a select few, mountains can be a many-layered text, that if deciphered carefully, opens a window into the history of life, ecosystems and the planet itself.

Adam Huggins 03:07

I mean, I mostly just go up there to see the wildflowers. What do you find most fascinating about mountains?

Mendel Skulski 03:14

I, you know, I love being able to look at the strata of rock, and be able to peel back time. You know, it looks unchanging, it looks immutable and timeless. But when you get up close, you can see all these transformations in Earth's history. All the tectonic, climatic, and evolutionary shifts that have literally determined the shape of our world.

Adam Huggins 03:41

Yeah, there's, there's also mushrooms up there too, right?

Mendel Skulski 03:45

I'm more than just the mushroom person. But yes.

Adam Huggins 03:49

I didn't... I don't mean to paint you into a corner, Mendel.

Mendel Skulski 03:52

That's okay.

Mendel Skulski 03:54

Today, we're gonna get elevated with some true mountaineers, who are building on a legacy that spans over a century of incredible environmental change.

Adam Huggins 04:05

That's right. And they're going to tell the story in their own words

Mendel Skulski 04:09

From Future Ecologies, this is Mountain Legacies.

Introduction Voiceover 04:16

Broadcasting from the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the Musqueam. Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh, this is Future Ecologies: exploring the shape of our world, through ecology, design and sound.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 04:35

Okay, so I'm Jeanine Rhemtulla, and I'm an associate professor in the Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences at the University of British Columbia. And I am... what am I? I'm a landscape ecologist by training, and I'm really interested in in large landscapes — and how they change across space and through time; and who the people are in those landscapes that are shaping that change, making decisions about how we want to live on those landscapes into the future.

Eric Higgs 05:04

And I've always wanted to be Jeanine.

Eric Higgs 05:06

I'm Eric Higgs, I'm a professor in the School of Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria.

Adam Huggins 05:12

Longtime listeners will remember Eric from the "Nature By Design" series that kicked off our third season. He's a friend, mentor, and now my colleague at the University of Victoria. And he also helped us produce this story.

Mendel Skulski 05:25

A story which begins way back in 1996 — in Jasper National Park, high up in the Canadian Rockies.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 05:33

I was a graduate student at the time: I was a master's student at the University of Alberta, in the department of renewable resources — of all awful names — doing a graduate degree. And I wasn't very happy in that graduate degree: I hadn't yet found the project that really made my heart sing. And I was actually ready to quit, to be honest. And then I was kind of casting about at the university, you know, just trying to find somebody that was doing interesting work that felt like it was the right fit.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 05:55

And somewhere along the lines of knocking on doors, I knocked on the door of Professor Eric Higgs. And he just started talking about this project that he was putting together: the Culture, Ecology, and Restoration project in Jasper. I don't remember what we talked about, I just remember being blown away by the interdisciplinarity of it: the way that he was bringing together people from all different disciplines, different perspectives on a question: what does it mean to do restoration in a national park?

Jeanine Rhemtulla 06:22

He said "your job on this project, what I want you to answer is, what did this national park look like 100 years ago?" And so the idea was that we were going to recreate the ecological history and the cultural history of the park, and bring those together to ask about how the landscape and the people in that landscape had changed.

Eric Higgs 06:40

It was way more challenging to answer that question than we ever expect it to be. So we thought that was the easy part: we walk in, we go to the archives, there'd be some books, you know, book chapters written about this, and that we'd be able to piece together on what the landscape looked like. We got quite desperate after the first few weeks, right? And we were having a dinner I recall around the table with a group and I just said "we have really got to go out, and everybody tomorrow has to figure out, like, can we find anything that tells us what this is like?"

Jeanine Rhemtulla 07:09

We thought about using dendrochronology, so you can core trees. But that's very painstaking, and you can only do it in small areas. So we'd looked, for example, for old historical air photos, right? That's always a standard place to go. But the earliest are photos from the 1940s. And so that got us back partway, but not the whole way.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 07:27

And so then yeah, I remember the day that I was talking to some of the wardens, just saying like "I'm looking for old photographs, or old something, anything that we can use to reconstruct what this place used to look like." And he said, "Oh, I got these old photographs in this desk drawer," and so walks me over the desk drawer, and he opens up the bottom. And then there's these just beautiful albums of pictures. And you would go like, page after page — black and white, and they were kind of like I don't know, by maybe five by seven, or six by four. Beautiful pictures, these kind of cryptic numbers in the upper corner where you could tell there was some kind of like, there was some kind of series or something... Front ends of the books had this little index in them that had station numbers. So they were something, but it wasn't quite clear who had taken them, or what they were. And they had a date in the corner: 1915.

Eric Higgs 08:11

That's about all we knew about them.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 08:13

That, and I remember... I remember that map — it was like an 11 by 17 map. And the map had numbers on it. And at some point, we put together that the numbers on that map matched the numbers that were in these albums. And we were like, "Oh, those are the photo stations where we would need to go to take those pictures." And I think you were the one that said we should go repeat them.

Eric Higgs 08:33

So we climbed... we sort of scrambled up to powerhouse cliff. We found an old animal trail and we followed it up. It wasn't very difficult to get up there. But we walked along the ridge of this cliff and you know, holding these historic photos out. We took photocopies, right?

Jeanine Rhemtulla 08:47

Mhm.

Eric Higgs 08:47

Yeah. And we got up along the ridge, and we kept looking, and it was like we weren't finding the right spot. And then eventually it was like, "oh my gosh, this has to be the right place." And then we looked at across the Athabasca Valley, and nothing made sense. And you described it as kind of vertigo. Like you have this interpretive vertigo, where you know you're in the right place looking at a photograph of that place. And then what you're seeing isn't anything like what it looked like.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 09:12

There were trees, everywhere we looked there were trees: there was this huge carpet of green trees, tall trees, thick homogeneous trees, right? And that's what we expect in a national park. That's what we come to know Jasper National Park to be, is trees, right? Because it's a protected area.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 09:29

But when you look at the pictures, the pictures are this patchy mosaic of all of these different little shrubby things, and there are some grass areas, and then there's trees of different types and textures: some coniferous trees, some deciduous trees, different heights of different trees. Like, just a mosaic — a mosaic of diversity.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 09:48

So here you are standing in the middle of a national park, which has been preserved intact to be the way that it's supposed to be. And yet we're looking standing in the same spot that these surveyors were 100 years before, and the park is fundamentally different.

Eric Higgs 10:03

So then we just walked away and left it all alone.

Eric Higgs 10:06

No, we started walking and we did a couple more stations, and then having a mathematical mind that you do you started to think "maybe I can actually reconstruct the vegetation patterns from these oblique photos. Wouldn't it be cool if we could like repeat all of the images in Jasper National Park." And so we started getting all enthusiastic about this idea. Because we now knew there were 92 separate locations, and from each location, there were multiple images. So there were a total of 735 images. And most of these were mountain tops.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 10:39

Never imagining that this would become bigger, right? Like we just thought this was this one survey, we focused our work on just this one space. So those were the pictures we were repeating

Eric Higgs 10:48

The story that's etched in my mind so strongly is the very last day of the second summer of this work, where we were wrapping the last station: we saved Pyramid mountain for the last, and that was the very first real mountain that Jeanine and I climbed. But by this point, after three years, we were like, pretty fit, and used to mountains. We shot the last photograph, and I had a bottle of bubbly stashed away and some smoked salmon. And we watched the ravens circling, and we had a just a wonderful time.

Eric Higgs 11:17

I don't think I would recommend champagne on a mountain top when you have to climb down as a life choice. But that was what we did. And we got off these big quartz boulders and down to where we were staying. And there was a package for us. It was from our colleague, Ian McLaren, who was an historian, literary historian at the University of Alberta — an amazing archival researcher as well. And it was the season and survey report from Morris Bridgeland, who was the surveyor. We knew the original name really well. And it was his report to the federal government on his 1915 survey in Jasper National Park. So at the very last day, the last moment of our survey, we finally knew where they had gone, and in what sequence. And it was fantastic. We read the whole thing as we're eating dinner and reading and it was like, "Oh, my gosh, they did this!" And they turns out, they had two camera crews, which is how they managed to get through all the photography in one season. And then we both kind of moved on from the project. And we thought, "this is our moment."

Eric Higgs 12:25

And then enter Rob Watt.

Rob Watt 12:29

I go by Rob, there's too many Bobs in the world

Eric Higgs 12:31

At that time, he was a park warden at Waterton Lakes National Park, and he was an inveterate historian, amateur historian.

Rob Watt 12:40

And for some reason, there were something like three dozen volumes of Morris Parson Bridgeland's photographs, on a shelf in the common area of the office. And I didn't understand the background at the time. I didn't even know who Morris Bridgeland was. I gathered from the book that he was a land surveyor, and he took a bunch of photographs. But we didn't have any of his maps, for instance, and of courses this was way before there's anything like an internet. They had a big map collection down in what was the admin office in Washington. So I poked around in their map collection. And lo and behold, there's a map of Waterton: three mapsheets with Morris Parsons Bridgeland's name on them, and camera stations!

Eric Higgs 13:28

And he said, You know, "I have maps that show, you know, where there was evidence — photographic survey locations, because it shows that on the map," and it turned out to be by the same surveyor that we were working with in Jasper: Bridgeland. He said, "and I have the index to views," which was all important because that tells you where they were. I mean, the names aren't always modern names, but at least you knew where they were. But he said "but I don't know where the photographs are."

Jill Delaney 13:52

And so Eric contacted us in about 2002, very interested in where those photos came from, and was there a bigger collection,

Mendel Skulski 14:04

Jill Delaney, lead archivist in photography in the private archives branch, at Library and Archives Canada.

Jill Delaney 14:12

I've actually been working with Eric for 20 years on this project. And I've only been at the archives for 25 years. So it's been a big part of my career.

Eric Higgs 14:22

And that's too long a story to spin. But we found out that these glass plate negatives were held in boxes at NRCAN — Natural Resources Canada, not at the National Archives. And they were actually, in a sense, lost.

Eric Higgs 14:39

I have this story. It's probably not accurate, but I like it anyway. It's a bit of a conspiracy tale: that some benevolent civil servant realize the value of these images and misfiled them. We did come across records and that's basically a destruction protocol. They were held on too long. They take up a lot of space. They're heavy. Nobody uses them. They're gone.

Rob Watt 15:01

Three grad students from the U of A went to Ottawa, to the one of the national repositories, where records go to die.

Eric Higgs 15:13

And they were walking along and just by accident, I think, out of the corner of their eye. And poking out from the bottom of one of these barcode tags was a number that matched the kind of sequence of numbers that was on the box. And they said, "Woah! Wait a second, can we take a look at that box?" and pulls it off shelf — super heavy. And it was filled with glass plate negatives. So were the rest of the boxes on that shelf.

Rob Watt 15:37

Lo and behold, they found them.

Jill Delaney 15:47

So these are what's called a half plate: about four inches by six inches. That's a relatively thin glass plate, a bit thinner than window glass, let's say — but not much. It's kind of the same as with a film negative, it's basically the same concept. It's just that instead of the emulsion being on the film, it's on glass.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 16:11

Alright, so our cameras — in the age before digital — our cameras used to use film. And when a camera took a picture on that film, it would make... the image that it recorded on the film was like backwards of what you actually see. So in places where, if you're using black and white film, where something was dark in real life, it would be light on the negative and where it's light in real life, it is dark on the negative. And you only get to see back what that real picture looks like when you put that negative onto a piece of photographic paper and shine light through it, where it reverses that image again, and it ends up looking like what it really looks like in real life. So if you're looking at the negative, your eyes have to kind of imagine the whole thing... backwards.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 16:56

There's maybe 100,000 glass plate negatives in the National Archives covering most of British Columbia. And they are spectacular images. These were the photographs that surveyors were taking at the turn of the century to make maps of this area.

Jill Delaney 17:10

The government was worried about American expansionism in the 19th century. So they started doing a boundary survey between the US and Canada in the 1860s.

Julie Fortin 17:24

The original surveyors, in the most case mountaineers or geologists, who were hired by the Government of Canada or by the provinces to to create these maps.

Jill Delaney 17:35

This kind of topographical survey. The problem was that when they hit the mountains, they realized that doing a kind of standard rod and chain survey was going to be really difficult, really slow, and really costly, and probably impossible, in some places.

Eric Higgs 17:53

The traditional means for surveying land was to establish reference points in the landscape. And then from those reference points, using fixed distances and elevational measurements, using transits and so on, you would get a sense of the topography, the elevational change and the distance. So you could create pretty accurate maps. So if you're moving across Saskatchewan, or what's now Saskatchewan, not so hard. Tedious, but not hard.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 18:19

Yeah, it's like having a tape measure,

Rob Watt 18:21

The Gunters chain

Eric Higgs 18:22

So the chains were part of a legally determined length

Rob Watt 18:26

66 feet long, divided into 100 links of approximately 9 inches per link

Jeanine Rhemtulla 18:32

And so that was why, when they came to the mountains, like you can imagine dragging your chains across the mountains...

Eric Higgs 18:37

Like "Woah! Now we have this really steep elevation, and we've got all this complexity around topography..." And to do that using traditional techniques is hugely laborious.

Julie Fortin 18:48

So what they would do is they would go to a mountain peak, they would level the camera, and then they would take a whole panorama around to look at all of the peaks that you could see from that one peak.

Mary Sanseverino 19:00

So let's imagine that you have three peaks: A, B, and C. So you'd get to peak A, you'd build yourself a nice big cairn. And then you'd take a set of panorama images, so that you could see peaks B and C. Then you'd go to B, build yourself a nice big cairn. And then you would shoot back so that A and C are in your panorama set. Then you'd go to C, build yourself a nice big cairn. You'd say, "Well, why the heck did you put a cairn on C? Isn't that extra work?" Yeah, you're going to D, and D is going to tie back to C.

Jenna Falk 19:32

And all the way through the mountains.

Julie Fortin 19:35

It was a very, like, calculated process. I don't think that it was done with artistry in mind. But the result is that some of the photos are absolutely beautiful, but that's also just the nature of the landscape and the subjects that they're taking pictures of.

Jill Delaney 19:50

It's not a tourist camera, right, it's a technical camera that had to survive the rigors of hiking and climbing through the mountain.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 20:00

And then that's what they were carrying around: they had these big boxes on their backs that would hold 12 glass plate negatives and this old camera. And so imagine climbing mountains with like a backpack filled with pieces of glass.

Jill Delaney 20:12

It wasn't nearly as cumbersome as some earlier processes, where you had to take all the chemistry and a dark room with you. But probably the equipment weighed about 40 pounds that they had to take up to the peak where they would actually do the photography.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 20:30

And so yeah, climbing a mountain is hard. But if you can climb a mountain and take pictures, and take your pictures, again, in this 360 degree circuit going all across — you're taking a picture of all the land that you don't have to drag the chains across.

Jill Delaney 20:43

And it dramatically shortens the amount of time the surveyors have to spend in the field. And then you could pack all of these negatives together —

Jeanine Rhemtulla 20:54

then they would send them back to the office in Ottawa, where they must have had a whole office full of people doing geometry, essentially right, to turn those oblique angles back into a proper topographic map.

Rob Watt 21:05

The maths is fairly complex. Of course, they had some pretty smart people working on it.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 21:10

Our earliest topographic maps of certainly of the mountains, but of much of other places in British Columbia were done with this kind of technique. But 100 years later, like we look at the pictures, and to have to turn those into top down maps is... it's just become an art that we've that we've lost. Like, we just don't do it anymore.

Mendel Skulski 21:29

And so began the Mountain Legacy Project, leveraging this massive collection of historical photographs, over 100,000 pictures covering almost all of BC, part of Alberta and the Yukon, to reveal over a century of change.

Adam Huggins 21:46

And to do that means repeating each and every photograph, on each and every mountain peak, one by one,

Alina Fisher 21:53

Okay, you have a photo, you go to the place where that photo was taken, you point your camera in the same direction, you try to take the exact same photo.

Eric Higgs 22:01

People who have done this a lot... so we have field crew members who've worked with us over the years. There's always one every summer who's kind of like the station whisperer, you know, who does the research with the photographs ahead of time before you go out into the field, and gets a sense of, you know, whether there's one location or two that this historical surveyor shot from. And then they just have a sixth sense, a pattern recognition that allows them to say, "I think it's over there."

Rob Watt 22:26

Because basically, you're going out and you're triangulating the reverse of what the surveyors did. They knew where they were. We're trying to trying to figure out where they were, so we're backtracking from their photographs.

Mary Sanseverino 22:39

Yeah, I know I have not been the only one that has been on the wrong mountain. We don't do it very often. But once in a while.

Jenna Falk 22:45

Well, it speaks to that it's an art and a science to find your right location.

Mary Sanseverino 22:50

Yeah with a little bit of mountaineering thrown in as well.

Mendel Skulski 22:53

You've heard from some of them already, but now it's time to meet a few members of the MLP field team.

Mary Sanseverino 23:00

Well age before beauty, I guess. So I'm Mary Sanseverino, and I am a retired member of faculty in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Victoria, Faculty of Engineering. And I've been a member of the Mountain Legacy Project since 2010. And still do a little bit of work with them from time to time.

Jenna Falk 23:24

I'm Jenna Falk. I was involved with the Mountain Legacy Project from 2011 to 2014, roughly, while I was doing my master's in the School of Environmental Studies at UVic.

Mary Sanseverino 23:37

And when I went in the field for the first time, I went as Jenna's assistant.

Jenna Falk 23:42

Which still does not make sense to this day.

Mary Sanseverino 23:44

Makes great sense, great sense to me.

Jenna Falk 23:47

Mary kept us alive.

Julie Fortin 23:48

So fieldwork was incredible. My name is Julie Fortin. I did my masters with the Mountain Legacy Project at UVic 2016 to 2018. I joke with my fellow MLP'ers that I peaked too soon, and I will never have another experience like that.

Kristin Walsh 24:05

So I've almost been... 10 summers in the Rockies now because of this project. My name is Kristen.

Adam Huggins 24:13

Kristen Walsh

Kristin Walsh 24:14

First became involved with Mountain Legacy in 2014. Went out for stellar field season with four amazing, strong headed women. What we do in terms of our work is very different from mountaineering. Because often people get to the summit, and then beeline it down to get to the sauna or a beer with friends. But our work really begins when we arrive on the summit.

Mary Sanseverino 24:41

You know, we work with the surveyors. We work with their with their work. And you're so close to this work, that really you feel like, like you know that person.

Jenna Falk 24:54

Because they all have a signature in their photographs

Sandra Fray 24:57

Bridgeland! That man was fearless. Every time we were doing one of his sites, I had this sort of like low-key dread. Because I just knew that wherever he said that that tripod, you know it was going to be not always the most low exposure zone: it was going to be right on that outcrop, right over that precipice, just to get that perfect angle and perfect shot. And we knew we're in for that day.

Sandra Fray 25:24

My name is Sandra Fray. So I worked as a field technician in the summer of 2016 and 2017.

Adam Huggins 25:31

And finally, Alina Fisher.

Alina Fisher 25:33

I am a PhD student in environmental studies. I'm also the research manager for environmental studies. So kind of wear two hats.

Mary Sanseverino 25:42

It's... it's so cool to be like kind of walking in their their footsteps. And even some of our techniques are very similar to the techniques that they used back at the turn of the 20th century. And their maps are, for the time, pretty accurate.

Jenna Falk 25:59

Very accurate.

Kristin Walsh 26:00

There is a somewhat of a science to it. But there's a good dose of intuition as well, that's hard to explain unless you've been there doing it. And sometimes you'll just arrive at the top and you can imagine where someone stood 100 years earlier, or sometimes there's a physical cairnnn that they built.

Mary Sanseverino 26:21

Oh yeah

Jenna Falk 26:21

Huge carins.

Mary Sanseverino 26:21

Huge cairns!

Jenna Falk 26:22

Like, you know, some were what, 8, 10 feet tall.

Mary Sanseverino 26:24

Mhm mhm.

Jenna Falk 26:24

Massive things.

Kristin Walsh 26:26

Then you need to snuggle into that cairn to take the picture. And sometimes the obvious spot is not the spot. And you'll spend hours... So definitely a lot of patience needed in lining up those photographs.

Jenna Falk 26:43

That was always like our our kind of type A personal challenge: in the foreground. Like how close can you get the foreground to match exactly. And some of the rocks were in the exact same place.

Mary Sanseverino 26:55

Same place, yep.

Sandra Fray 26:56

Yeah, I know. I'm always wondering, "Can I sacrifice a little bit of scientific accuracy right now, not to get attacked by wasps? Is this okay?"

Alina Fisher 27:04

Isn't the verdict "shhh?"

Sandra Fray 27:05

Yeah. The verdict is safety first.

Alina Fisher 27:10

Yes, safety is always the first.

Mary Sanseverino 27:12

So I was, well not recently, but a few years ago, I was on Eiffel peak in Banff National Park. And Arthur Wheeler was there 1903. And he built an eight foot cairn. That cairn is still there. The pin that he put in place is still there. I know because we were there in an electric storm, and the cairn started to sing at you. When that happens, you must leave.

Sandra Fray 27:40

One of these hazards that you're on the lookout for in the mountains is weather, primarily. It can be a beautiful day. Mountain weather will do what it does best, and it changes on a dime. There was one day where we were on a peak, and we were very focused on the photographs we were taking.

Julie Fortin 27:59

We're going about taking our pictures, la de la de da.

Sandra Fray 28:02

And there was a storm cell that caught us by surprise.

Julie Fortin 28:05

Uhh... I don't really like the look of those clouds.

Sandra Fray 28:07

And of course, with the storm cell came all of a sudden... hail that's pelting down on us, and everything got slippery. And because it was a heli drop-off, full hover exit, you know, just right on this sort of conical peak, we had a really hard time climbing down a little bit, not to be the highest point on that mountain.

Julie Fortin 28:27

And then we looked at each other and we saw that our hair was standing on end.

Kristin Walsh 28:30

There's certain times when you just don't want to be on top of a mountain. Not only do you not want to be, but you shouldn't be.

Sandra Fray 28:37

You could just really feel the static in the air. And I remember hearing these boulders next to us where we were sort of crouched, just... could hear them buzzing,

Julie Fortin 28:47

You can... hear the static in the rocks,

Kristin Walsh 28:51

Sort of like in between a cat hissing and something like sizzling in a hot cast iron pan.

Sandra Fray 28:59

Everything that was metal, from the pin on top of your ballcap, you could hear that kind of singing and... it felt very real in that moment.

Julie Fortin 29:07

So that was a learning experience. Always keep your eye on the clouds.

Mary Sanseverino 29:12

You know, I like to say when you go to the mountains "Nobody died. Nobody cried. Well, nobody died."

Jenna Falk 29:20

Some of them were happy tears, to be fair.

Mary Sanseverino 29:22

Very happy tears, especially going "Yes! We made it!"

Jenna Falk 29:27

There are tears of joy. And then there are tears of relief.

Eric Higgs 29:29

There's so many moments, but they were fun at the time. Weren't they?

Alina Fisher 29:33

I feel like it's Type 2 fun, because at the time, you're like... you're struggling. You're slapping yourself non-stop to keep the mosquitoes away, and sweat's dripping in your eyes, and your hair got tangled in a bush as you're walking past something. You're hungry. You're thirsty. "Oh crap. My three liters of water is not enough."

Sandra Fray 29:50

I feel like the most fun I've had on these projects, and then generally, is those times I'm also asking myself "Whose idea was this?"

Sandra Fray 29:57

"What are we doing here?" And then later you're like, "That was so much fun."

Alina Fisher 29:57

Yes!

Jeanine Rhemtulla 30:01

Type 2 fun.

Alina Fisher 30:02

Because it's fun... when you look back on it.

Sandra Fray 30:04

Yeah.

Alina Fisher 30:04

But at the time, there's a bit of swearing involved.

Sandra Fray 30:06

Yeah.

Eric Higgs 30:06

Yeah, I've also embedded Type 3 fun. Which is –

Jeanine Rhemtulla 30:09

Which is never fun?

Eric Higgs 30:10

No, it's mostly what you deal with office of [bleep bleep]. Don't... don't quote that.

Adam Huggins 30:18

All in all, this does not sound that different from my bad mushroom trip at the top of Black Mountain, back in 2010.

Mendel Skulski 30:26

But did you come back with a priceless dataset of 1000s of repeat photographs?

Adam Huggins 30:32

No, I... I did not. I was just happy to make it off the mountain alive.

Mendel Skulski 30:38

Well, now that we too are coming down out of the mountains, let's have a look at those photos, shall we?

Adam Huggins 30:45

We shall, After the break.

Adam Huggins 30:54

Adam.

Mendel Skulski 30:55

Mendel. This is Future Ecologies. And today we're hearing about the Mountain Legacy Project from the folks that made it happen.

Adam Huggins 31:03

In this second half of the episode, we ask "What can we learn from two sets of identical photographs, taken over a century apart?"

Brian Starzomski 31:12

We have this remarkable and very rare collection. It's very unusual to have data that's this old in North America: this remarkable collection of what landscapes looked like over 100 years ago. Aesthetically, it's really neat to see that but from the point of view of a scientist, this is very difficult to get data.

Mendel Skulski 31:34

Brian Starzomski, Director of the School of Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria.

Brian Starzomski 31:40

There are no other ways to get data like this, there are no other ways to look this far back in terms of what landscapes and what the ecology of the West looked like.

Mary Sanseverino 31:49

The... the fidelity of the information that are on the historic glass plates, it's hard to beat that. Now, mind you, it's an oblique view.

Brian Starzomski 32:01

Interpreting oblique photos is more difficult than interpreting photos or data that's collected at a right angle, which is what satellite derived or remote sensing data is.

Mary Sanseverino 32:12

And I can tell you, as a person that does a little bit of software, it's not easy to go from the oblique view to something that goes on to a 2d map — that goes to the orthographic, the... the look down view, like an air photo. You can do it, but it's not easy.

Mary Sanseverino 32:30

So in the photograph, the pixels that are in the far distance, those pixels are huge. And the pixels that are in the foreground, those pixels represent a very small area.

Julie Fortin 32:42

If I were to tell you that like there are 1000 pixels of coniferous forest, it actually kind of matters where they are on the photo if they're in the foreground or the background.

Mary Sanseverino 32:52

So in the distance, one pixel, huge area, foreground, one pixel, tiny area.

Julie Fortin 32:58

This whole process of projecting these photographs is actually computationally pretty difficult, but doable now.

Mary Sanseverino 33:06

It's applied linear math, and a lot of programming. And we wouldn't call it research if we knew what we were doing. So we're really, really at the bleeding edge, if you will. What we do with this is take land cover classifications that are made from the photographs. So imagine you're looking at a photo that was done in 1897. And you look at the photo and you classify it and you say, well, that's grassland and that's –

Sandra Fray 33:35

Mixed wood forest

Mary Sanseverino 33:36

and coniferous forest

Sandra Fray 33:37

Open meadow

Mary Sanseverino 33:38

Shrub

Sandra Fray 33:39

Barren rock

Mary Sanseverino 33:40

That's ice. And then you do that for a modern photo. And then you compare the two.

Sandra Fray 33:45

Yes, that's when you get into the analytic side of things. And it's not just all fun and games in the mountains... I've heard!

Mary Sanseverino 33:54

I've got a couple of takeaways. Number one: loss of ice. The loss of glaciation is absolutely jaw dropping, staggering. Second: industry in the landscape. Several times, we were on the land, trying to line up these images and everything worked except for one. And that's because the mountain wasn't there anymore.

Brian Starzomski 34:18

Probably 5% of British Columbia's GDP comes out of coal mines. Coal mining is done by mountaintop removal.

Mary Sanseverino 34:26

It's really crazy to see the glacier gone. But when your underlying geological structure is just gone, it's... it's disconcerting. And I'll say a third one: Alpine treeline ecotone creep up slope. So that is in so many photos.

Brian Starzomski 34:46

When people think of the treeline, I suppose they probably think of this razor sharp delineation, between forest below it and then alpine tundra or wildflower meadows above it, and it's often not really like that.

Andrew Trant 35:00

As you get closer to that boundary, which we call the treeline ecotone, the trees start to change their growth forms.

Adam Huggins 35:06

Andrew Trant, Associate Professor in the School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo.

Andrew Trant 35:14

And so you start to get trees that are growing less vertically more horizontally. The growth form that we refer to is called Krumholtz,

Brian Starzomski 35:21

Krumholtz, these trees that are very difficult to walk through, you see them in mountainous places all over the world, the conditions are such that they can't grow very tall, certainly less than two meters tall,

Andrew Trant 35:33

You can have the same species growing in the forested area that you see up just around the edge. And one can be 100 feet tall, and one could be three feet tall, same species, but it's just the environment that really drives that growth form.

Brian Starzomski 35:48

And it's just this impenetrable thicket that is very difficult to get through, but absolutely filled with bird life. When we measure treelines, we do it in a variety of different ways, we may say that a treeline is the highest elevation that a certain height of tree goes. We might say that this is where the two meter trees run out. Or we might say that the treeline is the limit of where a certain density of forest exists.

Andrew Trant 36:19

One important piece of this puzzle when we're thinking about these boundaries and thinking about treeline is that they are, they are in some ways controlled by temperature. So as things are warming, then we would expect trees and ultimately, this whole complex community to be able to grow higher up the mountain. In most cases, that's what we saw, it was kind of an overwhelmingly clear signal of change in that direction.

Jeanine Rhemtulla 36:45

For all of the quantification that we've done, being able to transform these into kind of like hard numbers that we always like to have, as scientists... I still think that some of the most value comes from these pictures, is their evocative value to audiences: to be able to look at those pictures side by side, and to just be able to see the amount of change in the landscape. And then to be able to dig in and ask these questions like "Okay, so these these landscapes are completely changed. First of all, which one do you think is the present, and which one do you think is the past?" And so often people say, "Oh, well, the one that's got trees everywhere, that has to be what it looked like 100 years ago. And the one that's patchy, and it's got like little shrubby stuff, that must be what it looks like today, because we've obviously cleared the land, right? It used to be treed, and now we've cleared it." because that's again, our image of what people have done the landscapes, and it's bad if there's no trees, and it's good if there's just homogeneous trees everywhere.

Julie Fortin 37:35

Yeah, a lot of people that I have spoken to have said, "Oh, more trees. That's good, isn't it?" And, in fact, no, especially a lot of the places where there are these denser forests now have a lot higher wildfire risk. And so that's risk to the community, a whole bunch of other risks for climate change. Because if you have these large swaths of connected forest, it's a lot harder to fight these fires if they do get into places that we don't want them to be. It's also bad for biodiversity, in the sense that, because the landscape is more homogeneous now, species that relied on these diverse bits of habitat have less of it, and therefore they're suffering, whereas species that were already dominant are doing better.

Andrew Trant 38:21

And in a mountain environment, you are limited with the amount of area that you have, as you go higher up the mountain, the area decreases because you're looking at something that's kind of conical.

Brian Starzomski 38:31

That's right. And actually, those alpine meadows, those mountaintop meadows above the treeline are some of the most remarkable and diverse habitats for a variety of very rare plants, often with very restricted ranges, because they're just found on those mountain tops, or hugely diverse and abundant butterfly populations.

Brian Starzomski 38:52

So one of the really remarkable things about being on a mountaintop in July or August, are the 1000s of butterflies flying around. And as treeline moves up, those habitats get smaller and smaller, and this is going to happen all across southern BC. Treelines will move up, we'll have more trees, sure, in mountains. But we'll have much less Alpine habitat, which means much less habitat for things like White Bark Pine, for really beautiful rare and endangered butterflies, for really rare and range restricted plants. And just that habitat that we really love. A lot of people really love those lush mountain meadows or those rocky craggy peaks. There are going to be fewer and fewer of those as forests move up more and more in the mountains.

Bill Snow 39:43

The pressures that are being put on mountain landscapes — it affects our water, affects our air, our culturally important and sacred places. But probably most of all, it affects our wildlife. And gradually, they are being squeezed out of their their habitats.

Mendel Skulski 40:06

Bill Snow, Acting Director of Consultation for Stoney Tribal Administration,

Bill Snow 40:11

I work with the three first nations that comprise Stoney Nakoda, which are the Bearspaw First Nation, the Chiniki and the Goodstoney First Nation.

Mendel Skulski 40:26

The reserves of these three nations are just west of Calgary, a few hours drive south of Jasper, and near another famous National Park: Banff.

Jenna Falk 40:35

You drive through the Rocky Mountains "Oh, isn't it beautiful?" But then the flip side of that is this is all grown in because fire has been suppressed for decades. And what does that mean for wildlife and ecosystems? Fire would be naturally occurring here if it wasn't put out as soon as possible. So the ecosystems have changed, the wildlife patterns and habitat has changed.

Bill Snow 40:54

When fires excluded, we get what we have right now. We have overgrowth, so that even wildlife can't find access into some areas. That may bottleneck wildlife routes, to go into certain areas where they may come into more human conflict. And then those those overgrowth areas become tinder boxes for natural or manmade events to to become a fire hazards.

Eric Higgs 41:27

Yeah, working in, say, the front ranges of Waterton, where you're aware of mountain pine beetle as an insect pathogen, and then fire suppression, and then the desire now to prescribe fire and put fire back on the landscape. And so many other drivers of change, you know, shifting that ecosystem around.

Eric Higgs 41:44

And then you get these events that just leave you breathless. So in September 2017, a wildfire came in over the Continental Divide into Waterton. Fortunately, the national park staff had done early warning on this fire and managed to evacuate people and so on. But I've heard some describe it as a slow moving explosion. The fire came in, you know, in the early evening. And by midnight it had gone through the park. Took out over 35% of the park area in that period. And a lot at very high severity, meaning the fire really, really burned hot in that area.

Eric Higgs 42:23

People were frightened by that fire. I mean, people were traumatized by that fire. It was so severe and so fast moving. And so it was a kind of a system changing event. And clearly one that had been, in a sense, unprecedented.

Bill Snow 42:37

There is work going on within Banff National Park — firebreaks firesmart programs, that's good. But this whole policy of no burning, period, over the last 100 years has created... is creating a large problem. And that's going to affect everybody, from people who visit the park, to the people who live there. And as Stoney Nakoda, that's part of our traditional lands. So it will impact us as well.

Mary Sanseverino 43:10

This speaks to something that you have to come to terms with if you're going to work with these photos. These photos are colonial artifacts. They are deeply colonial. The reason that they exist is because the country needed to make maps. And what did they need to make maps for? They needed to make maps so that the resources could be divvied up.

Eric Higgs 43:33

The images are arguably a pre-eminent colonial record. They were about surveying for resource extraction, surveying for transportation, and surveying for settlement. So they were really all about exclusion of Indigenous peoples

Jeanine Rhemtulla 43:48

On this idea that people are necessarily bad. We get rid of them, and now we've got the park and we're protecting it.

Eric Higgs 43:54

So yes, very effective from a colonial perspective, but also very effective in producing a lot of images that we might be able to use for decolonial purposes.

Mary Sanseverino 44:05

And so how might we do that? What about using them to inform First Nations studies of land? Maybe, you know, returning to burning practices, for example.

Bill Snow 44:17

In traditional times, I believe that traditional burns were used in select areas, to regrow areas for purposes of harvesting, not only plants and medicines, but for wildlife. And was also used to clear pathways to create access,

Jeanine Rhemtulla 44:41

Right? And here were these photographs that showing well oh gosh look like this park that we've "protected" (here I'm using scare quotes) "protected" for 100 years and look, it's fundamentally changed. And why is this? And it's forcing us to consider what's causing this change, what was maintaining the ecosystems that looked the way they did 100 years ago. And oh look, it was actually people taking care of these lands that made those lands look like what they did.

Bill Snow 45:05

When the Stoney people would travel through different areas, you know, they wouldn't go and cut down a brand new tree, a green tree. They would use the dead wood in that area. So just by living in camping in a certain area, they would take all of that away from that landscape. And they would always be moving around. So they'd go from one area to another, and another clan or family might be behind them doing the same thing. And so you have this maintenance going on, just by Indigenous people moving through those areas. But you don't have that anymore.

Bill Snow 45:47

We have been in talks with Banff National Park on reintroducing Indigenous burning. Not all areas, but select areas. I'm not saying that fires are going to solve everything. But those past practices held those areas in in a certain kind of balance.

Adam Huggins 46:09

And of course, humans and fire are not the only ecosystem forces at play here. The historical dynamics of these mountains also included large grazing mammals: Like bison.

Bill Snow 46:22

We see that by having wildlife like bison out there, they are able to impact that landscape. They are able to feed on not only the grasses, but the willows. They rub up against the trees when they move around. They trampl down on the new growth that comes up. When bison are out there, they hold the forest in check from overgrowth. They make trails... through willows and through the bush, to get to the places that they want to go to. And so they have an impact on the landscape that we don't totally fully understand yet.

Bill Snow 47:12

Stoney Nakoda have been in support of the bison reintroduction project, going back to 2014. They were translocated into what's called the Panther Dormer area — sort of the northeast part of Banff National Park. There's no roads to get in to this particular place. So the bison had to be airlifted by crates in helicopters 30 kilometers into the actual reintroduction zone. They've gone from 16 head in 2017, and today there are over 90 head.

Bill Snow 47:57

There's a lot of overlap related to wildlife studies, related to fire, related to land planning, especially in Banff National Park. Landscapes today are drastically different from how they looked 100 years ago. So that's really important to know.

Mendel Skulski 48:17

But beyond revealing those changes, and offering some tools to intervene, these photos can play a part of an even more fundamental question.

Eric Higgs 48:27

Stony Nakoda nation have used the images to sort of say, "Well, what were these mountains called before? And let's rename them, you know, let's at least get them into cultural currency."

Bill Snow 48:39

Those places have a story and a name that hasn't been told yet. It's important because many of the places, especially in the Canadian Rockies, do not reflect the Indigenous name or the Indigenous meaning.

Bill Snow 49:00

One of the first pictures that we were able to work on with the Mountain Legacy Project is the first picture from the east side of Lake Louise. And yes, it is a beautiful place, but it's also a spiritual place. And that's not what visitors understand when they come there. Lake Louise, you know, "crown jewel of the Canadian Rockies." And the person who's credited with the discovery of Lake Louise is an early mountaineer named Tom Wilson.

Bill Snow 49:36

August 21, 1882. Tom Wilson was working on the railway when they came through that area. And at different times during the day they could hear like a big rumble off in the mountains, like an avalanche or rock slide. There was a group of Stoney people camped nearby in the Banff area. And so he went to go visit them and ask them "What's that sound? That rumbling sound." And they told him that "That's God speaking to us." And so he got all intrigued, "Well where's this place? I want to go see this place." So one of the guides, his name was Edwin Hunter, Stoney guide, and he took him up there to go see the lake. And when they got up there he could see those rock slides, so Tom Wilson was guided up there by a Stoney, but he's credited with the discovery. So if places and names have meaning, we're not communicating that meaning. We were able then to take that photo, and then add in Stoney name for Lake Louise: Horâ Juthin Îmne, which is the Stoney translation for Lake of the Little Fishes. We thought that had more... more meaning and more reflective of what that place is. So when we have a chance to say "Yes, this is Horâ Juthin Îmne," that tells us that there's fish in there — small fish — And that there's also additional names in that area that we haven't got yet. So I'm talking about Mirror Lake, and Lake Agnes, and other peaks in that area.

Bill Snow 51:36

It's really meaningful to be able to get to work on these types of images within the Stoney Nakoda. territory. The images have been used towards a process of colonization. So why can't we use those images towards the process of Indigenisation? It's taken 150 years to get to this point where we can relay some of these images. But now people know

Eric Higgs 52:07

The images are open to anybody who wants to use them. We built this custom database, called the Mountain Legacy Explorer, and it holds all our historic images and all our repeat photographs. We collaborate with the National Archives in doing this. And so that's been a big commitment for us — is to daylight these images to make sure that people can get access to them.

Bill Snow 52:25

And then not only do we have that as a tool, but then it speaks to us now to say "What are we going to do about it? Are we going to take all those images and put them in nice frames and keep them on the shelf? Or are we going to take what they're saying, and apply it?" Is that something that can be impressed upon regulators and government to say "This is how we need to be managing landscapes towards. This is how we need to be providing access for wildlife."

Jenna Falk 52:59

You know, we're fascinated with change, at the same time as being really afraid of it sometimes. We don't like change, but we also love to study it, whether it's one day to the next in our flower garden, or 120 years to the next in a mountain pass. And through these photographs, we have such a unique perspective in the Rockies to see that long term change that we don't necessarily in low lying areas. So I think it's for anybody to recognize that landscapes change for many reasons, and they're going to keep changing. And with climate change, there's a sense of loss when we lose the landscapes that are familiar to us. But there's also, I think, a good reminder in these photographs that we have an opportunity to support species and ecosystems through that inevitable change.

Mendel Skulski 53:48

And if you'd like to dig into that longterm change for yourself, you can explore all the photos and all the data of the Mountain Legacy Project at mountainlegacy.ca.

Adam Huggins 54:00

It's actually really cool, you can slide back and forth between the historical photo and the modern day photo and see the changes on a really, really detailed level.

Mendel Skulski 54:10

Yeah, and they're beautiful.

Adam Huggins 54:12

They are beautiful. This episode was made possible by a Pathways to Impact grant: mobilizing knowledge in support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals,

Mendel Skulski 54:21

Specifically those pertaining to clean water, climate action, and life on land.

Adam Huggins 54:27

And of course, the Mountain Legacy Project itself wouldn't have been possible without all of the people that you heard here, and many, many more.

Mendel Skulski 54:35

So thanks to Eric Higgs, Jeanine Rhemtulla, Rob Watt, Mary Sanseverino, Jill Delaney, Andrew Trant, Alina Fisher, Brian Starzomski, and Bill Snow.

Adam Huggins 54:48

And the amazing field team alumni, including Julie Fortin, Kristin Walsh, Jenna Falk, and Sandra Fray.

Mendel Skulski 54:57

Plus everyone who we didn't get to speak to: Rick Arthur, Ian MacLaren, Navarana Smith, and countless others — grad students, helicopter pilots, archivists, etcetera, etcetera.

Adam Huggins 55:10

Future Ecologies is a completely independent production. So thanks as always, to our patrons who support this show. To join them and get early episode releases, extended interviews and other bonus content, including access to the best Discord server on the web, go to patreon.com/futureecologies.

Mendel Skulski 55:30

This episode was produced by me, Mendel Skulski.

Adam Huggins 55:34

And me Adam Huggins

Mendel Skulski 55:35

With music by Thumbug, Erik Tuttle, Shadow Acid, Sage Palm, and Sunfish Moon Light.

Mendel Skulski 55:47

Okay, see ya!