Collage of images by Sonder Quest, Frankie Lopez, and Ganapathy Kumar

Portrait of Jim Corbett by Sterling Vinson

Courtesy of Pat Corbett & Cindy Salo

As of August 2021, Jim Corbett’s Goatwalking has been re-issued in a new 2nd edition, with all proceeds supporting Pat Corbett. Purchase a hard copy or an e-book here

Summary

Jim Corbett was not your typical rancher. Over the course of decades roaming the borderlands of the desert southwest, he developed a practice that he referred to as 'goatwalking' - a form of prophetic wandering and desert survival based on goat-human symbiosis. For Jim, 'goatwalking' provided both physical and spiritual sustenance, and allowed him to become at home, for a time, in wildlands.

To many, this modern-day Don Quixote would seem an unlikely figure to have sparked one of the most important social movements of the 20th century, but to those who knew him well, it was hardly a surprise. Even today, his influence is felt throughout the borderlands of the Southwestern United States, and beyond.

This is the story of a man behind a movement – the biographical first part of a 4-part series.

From Future Ecologies, this is Goatwalker, Part One: On Errantry.

Ready for Part 2? Click here

Three small corrections for this episode:

Jim received his BA from Colgate, not Columbia

Jim was raised with only 2 siblings, not 3, after one of his brothers died during childbirth

Bahasa Indonesia is better described as the national language of Indonesia, rather than as a “standardized” version of Malay or Indonesian

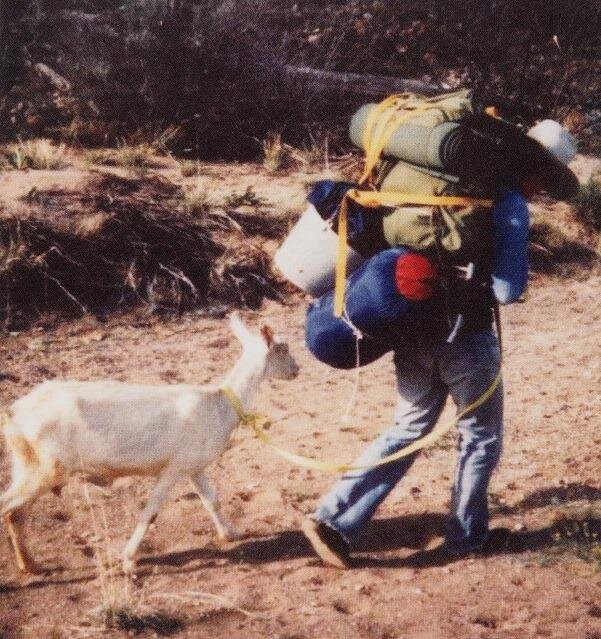

Jim on a Goatwalk

Courtesy of Susan Newman

Show Notes

This episode features Ann Russell, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Jim Corbett, and Miriam Davidson. Narration by Phillip Buller.

As of August 2021, Jim Corbett’s books, both “Goatwalking” and “Sanctuary for All Life” have been re-issued as new 2nd editions, with paperback and e-books available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Find photos of Jim on his memorial page with Saguaro Juniper

Music by Hidden Sky, People with Bodies, Ben Hamilton, and Sunfish Moon Light. Goatwalking Theme by Ryder Thomas White and Sunfish Moon Light.

Archival music (Que Partes El Alma & The St. Louis Blues) from Project Gutenberg

This episode was produced by Adam Huggins and Mendel Skulski.

Special thanks to Ilana Fonariov, Teresa Maddison, Susan Tollefson, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Nancy Ferguson, Tom Orum, Gary Paul Nabhan, Gita Bodner, Amanda Howard and the University of Arizona, Charles Menzies, Sadie Couture, Phil Buller and Jan Adler, Michael Smith and Cathy Suematsu, and Danny Elmes.

This series was recorded on the territory of the Tohono O’odham, and produced on the unceded, shared, and asserted territory of the Penelakut, Hwlitsum, Lelum Sar Augh Ta Naogh, and other Hul’qumi’num speaking peoples. It’s important to acknowledge that the public lands that Jim would walk his goats on are also stolen Indigenous lands, as are the lands we live on.

This episode includes audio recorded by seenms, soundbytez, rambler52, lonemonk, visualasylum, kgunessee, and RHumphries, protected by Creative Commons attribution licenses, and accessed through the Freesound Project.

Citations

Corbett, J. (1992). Goatwalking. Penguin Books

Davidson, M. (1979). Miriam Davidson papers. University of Arizona Libraries, Special Collections (MS 433)

Davidson, M. (1988). Convictions of the Heart. Univ. of Arizona Press

West, M., et al (2017, June). The Valley View #6 (Cascabel Newsletter)

You can subscribe to and download Future Ecologies wherever you find podcasts - please share, rate, and review us. We’re also on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and iNaturalist.

If you like what we do, and you want to help keep it ad-free, please consider supporting us on Patreon. Pay-what-you-can (as little as $1/month) to get access to bonus monthly mini-episodes, stickers, patches, a community Discord chat server, and more. This season, we’re taking a tour of some of our Seaweed Sojourners, with the help of Josie Iselin.

Future Ecologies is recorded and produced on the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the WSÁNEĆ, Penelakut, Hwlitsum, and Lelum Sar Augh Ta Naogh, and other Hul'qumi'num speaking peoples, otherwise known as Galiano Island, British columbia, as well as the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the Musqueam (xwməθkwəy̓əm) Squamish (Skwxwú7mesh), and Tsleil- Waututh (Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh) Nations - otherwise known as Vancouver, British Columbia.

Transcription

Introduction Voiceover 00:03

You're listening to season three of Future Ecologies.

Mendel Skulski 00:08

Hey folks. What you're about to hear is a project that's been years in the making. It's new territory for us, both figuratively and literally. My co host, Adam will be taking the reins on this series. And to be honest, he hasn't told me exactly where it leads. All I know is that it starts here – with the story of a rancher in the borderlands of the American Southwest: An iconoclast whose relationship with the land would come to shape one of the most important social movements of the 20th century.

Mendel Skulski 00:39

Just so you know, the second half of this episode mentions suicide. It's heavy, but brief.

Mendel Skulski 00:46

Okay, let's get to it.

Adam Huggins 00:54

In the spring of 1970, an unexpected visitor showed up in 16 year old Ann Russell's classroom in the Sierra Nevada foothills of California.

Ann Russell 01:03

He arrived one day at John Woolman School, which is in Nevada city on a ranch – it's a Quaker school. He was friends with the principal, but I didn't know that. He just arrived with his goats and his dog.

Adam Huggins 01:17

The dog's name was Puck. The man's name was Jim. And the two goats that he brought with him that day were part of an invitation that he had come to deliver to Ann and her fellow students at the Quaker school.

Ann Russell 01:29

We had a lottery. He announced that he wanted to lead this group of eight students to practice living in harmony with the land.

Adam Huggins 01:39

The plan was to spend six months on a ranch in southern Arizona with Jim, his wife, Pat, Puck, and the goats. He didn't sugarcoat it: The academic program would be demanding, and the accommodations humble. The goal was to practice radical simplicity.

Ann Russell 01:57

I didn't really know what it meant – what Jim was really talking about us doing but he had this schpeel that he gave, and he said "dedicated hedonists need not apply". And so of course, I put my name in the hat.

Adam Huggins 02:13

At the time Ann told me she was open to anything from dedicated hedonism to radical simplicity. And it just so happened that Jim Corbett, a man who hewed much closer to asceticism than hedonism was the one who showed up at our school that day, with his goats.

Ann Russell 02:30

I remember he pulled out a name and he said "Ann", and Ann Sotelo started to scream with joy. And then he said "Russell" [laughs].

Adam Huggins 02:45

And so in September of 1970, Ann and seven of her classmates arrived, sight unseen, at a small ranch in the Sonoran Desert, outside of Tucson, Arizona.

Ann Russell 02:56

And we had a little house on the ranch, Pat and Jim had a big house.

Adam Huggins 03:02

The students learned to milk goats, dig pit houses, and ride horses. Classes would take place outside under an old mesquite tree, and would feature lectures by Jim on the topic of the day, followed by discussion. The students were captivated.

Ann Russell 03:18

He was a very compelling person. And part of it was, he had a vision for how society and maybe just starting with a few people could live with the earth. And he was relentless about thinking it through – about how it could work, about the philosophical underpinnings. And it was really attractive to a lot of people.

Adam Huggins 03:48

To some, this might sound like the makings of a cult, but that was kind of the milieu you have the 1970s. These were Quakers students interested in alternative lifestyles and getting back to the land. And if Jim was a cult leader, he was far from typical.

Ann Russell 04:03

You know, he was a kind of a wizened, skinny person. In fact, he made he was started... when we were down there, he was making smoothies for us out of goat yogurt, and we were gonna market it as Jim Corbett's health drink with a picture of Jim on the label. Nobody would buy it [laughs].

Adam Huggins 04:24

The discussions and smoothies were memorable, if not marketable. But the culmination of the students semester in the desert was a two week expedition into the Galiuro mountains with Jim and herd of goats with names like White Queen, Sansha, Nero, Dearly Beloved, and Magpie Socialite Piddleteat.

Ann Russell 04:49

Pretty much everybody had been backpacking, I think, but we were urban kids from you know, I don't think our family as being wealthy but we were able to go to a private boarding school. So we're privileged kids. And this was not something we had ever done.

Adam Huggins 05:11

The students along with Jim would be part of the herd. This meant that each student had to spend time with a goat until they imprinted on each other, so that the goats would stay with the students and allow them to milk them without restraints.

Ann Russell 05:25

Before they knew that we were theirs, that they were ours, that we were together – they would, you know, they would fight. When you first milk a goat, she doesn't know you, she'll kick and try to get you out of her way. But then, Nero, my goat, she just looked at me suddenly, just these melting eyes – like I was her baby. And then she wouldn't let me out of her sight.

Adam Huggins 05:50

Now that they were bonded, they were ready for goatwalking.

Ann Russell 05:53

We loaded up our backpacks. We had only oatmeal – oatmeal and Cream of Wheat for a little variety [laughs],and raisins, and brown sugar, salt, and then we had the goat milk. That was what Jim said. He says it in his book, that for your nutrition, that's really all you need. That's what you need. And whatever we could collect.

Adam Huggins 06:15

Collect, that is, from the desert. For two weeks, this group of aspiring back-to-the-landers would literally be living off the land. And when the day finally arrived...

Ann Russell 06:26

We took the truck and horse trailer full of goats into Tucson, got maps in town, and then Pat dropped us off on the Cascabel road.

Adam Huggins 06:35

If the side of the road seems like a strange place to drop off a group of students and goats, it's because they ran out of gas.

Ann Russell 06:43

And when I think of this now, I think, you know, being an adult and a parent, the things that they did with us, took so much courage. And they ran out of gas, and we ran out of gas, and we unloaded the goats, and climbed through the fence and onto public land. And Jim told us, you know, this is public land, we own it. And we headed toward the mountains. And we didn't – we weren't starting where we thought we were going to start. So Jim, you know, there was no water source initially. And we didn't know where the water was going to be.

Adam Huggins 07:24

The only water around was what they had brought with them. But Jim was adamant: those canteens were off limits.

Ann Russell 07:31

You know, we're privileged kids. Our lives were threatened because there wasn't enough water. And Jim said "No, you can drink milk, warm goat milk". Not terribly appetizing when you're really thirsty.

Adam Huggins 07:46

Still, despite their collective thirst, the students saved the water for the goats. Like Jim said.

Ann Russell 07:52

You know, goats, they become bonded with you when you know. And there's a social structure within a goat herd. And we became part of that social structure.

Ann Russell 08:04

And that was part of his philosophy is we're not separate. We're part of the herd, we're part of the desert. We can be part of the desert in a low impact way. We had a tremendous amount of respect for him. We thought he knew everything.

Adam Huggins 08:23

For those two weeks out in the desert, the herd of students survived on goat's milk.

Ann Russell 08:29

And oatmeal. We loved we loved our oatmeal. We looked forward to every meal with oatmeal. A lot. We had food dreams, though. And in the morning around the fire when we were cooking our oatmeal, we are talking about food dreams. And one of them – one of the guys had lived in Switzerland and he talked about raclette: melted cheese over bread. Oh, yeah, we lost we all lost a lot of weight. We lost our spoons. And when we lost our spoons, we made chopsticks.

Adam Huggins 09:01

They covered a lot of ground and the terrain was rough: exposed hillsides and dry washes. One day, they came to a particularly steep hill covered in the aptly named shrub, cat claw

Ann Russell 09:13

It was very steep and to keep from sliding back you'd grab a bush so you get scratched and we were wearing shorts because we were clueless. So then we get all scratched on our knees – hands and knees. It was awful, really awful.

Adam Huggins 09:28

Just when it seemed like they'd never make it. One of Ann's classmates saved the day.

Ann Russell 09:33

He said "well, it's not much like sailing". And that just made me crack up. It made everybody crack up and we were able to somehow struggle to the top of this ridge because he made us laugh.

Adam Huggins 09:51

Under the harsh blue sky, they found a sense of peace.

Ann Russell 09:55

And then on the top of the ridge we locked up the ridge a little ways and we hit this grove of maple trees that had lost their leaves. So the branches were all gray and naked. It was gorgeous.

Adam Huggins 10:18

There were lots of quiet moments during those two weeks. And on one of those quiet goatwalks, Jim turned to Ann.

Ann Russell 10:26

So Jim asked me what my calling was. I didn't know. I said "I don't know". And he said, "Well, you should think about it. Because you're smart enough, somebody will find you useful if you don't figure out what your life is about". And it was like, oh – that has stuck with me... forever.

Adam Huggins 10:57

After two weeks in the desert, Pat drove out with the horse trailer and collected the herd from their final days camp. A little leaner, perhaps, but filled with a sense of accomplishment. And for Ann, like so many other people who would come into contact with Jim over the years, the experience changed the course of her life. Underneath the humble exterior of this philosopher turned goat herd was a true visionary, activist, and conservationist who would inspire generations of people in the Borderlands and beyond, to care for the earth and for one another; to seek what he would call a sanctuary for all life.

Adam Huggins 11:50

And so much like Jim, I'd like to extend an invitation for you to join me on a sojourn into the desert, sight unseen. Jim Corbett and his goats are, of course, the central characters. But the story is so much bigger than you could imagine. And it's still playing out to this day in the Borderlands of the Sonoran Desert, and across North America, from Future Ecologies, this is Goatwalker, part one: "On Errantry".

Adam Huggins 12:46

My name is Adam, by the way, and I'll be your host for this series. for regular Future Ecologies listeners, you may miss Mendel's voice, but they're still in the mix, just in a more editorial capacity, so that I can tell this story that I've been working on for nearly four years now.

Adam Huggins 13:05

I first discovered Jim's work and ideas in a tiny one-room goat hunting cabin in the subalpine rock fields of Pitt Island in British Columbia. The unseeded traditional territory of the Gitxaala First Nation. The goats in question were not actually goats at all, it turns out the mountain goats of Western North America are actually considered antelope goats, and are more closely related to musk oxen than true goats. Also, I wasn't really there to hunt them. I was part of a field crew led by Gitxaala UBC professor named Charles Menzies, who you might remember from our Kelp Worlds series. We were attempting to trace the roots that his ancestors would have used to hunt mountain goats. And walking in their footsteps, we did catch tantalizing glimpses of those iconic, snowy white ungulates up there that summer. But that's another story.

Adam Huggins 14:00

Now, as it happened, summer up in the coastal rain forest of Gitxaala territory is like no summer that I've ever experienced. This is a part of the world where bogs can form on steep hillsides, just due to the sheer quantity of precipitation. Camped out for weeks on end in the subalpine, we'd often retreat to this cramped, one room cabin, and wait out the periodic rainstorms, which could last for days. As a result, I spent a lot of time in a small room with the field crew, keeping the stove hot and reading books. I can't really remember what I brought to read that first expedition. But I quickly realized that everybody else in the cabin was reading books about mountain goats, with titles like "A Beast the Color of Winter", and "Mountain Goats: Ecology, Behavior and Conservation". I realized belatedly that I should get with the program, and so on a trip back home, I grabbed the only goat-related book in my house which bore the unusual title:

Goatwalking 15:01

"Goatwalking: a Guide to Wildland Living – a quest for the peaceable kingdom."

Adam Huggins 15:07

I was dimly aware that the book was a gift to my partner from a farmer friend of ours, but that was about the extent of it. I settled up in my bunk with my sleeping bag, and cracked Goatwalking open for the first time.

Goatwalking 15:24

Two milk goats can provide all the nutrients a human being needs, with the exception of vitamin C and a few common trace elements. Learn the relevant details about range goat husbandry, and something about edible plants and with a couple of milk goats, you can feed yourself in most of the wildlands – even in deserts.

Adam Huggins 15:46

From the very first words of the preface, I was hooked.

Goatwalking 15:50

Civilized human beings don't fit into untamed communities of plants and animals as members of the community. Instead of adapting to wildlands, we tame them. The goat-human partnership can fit in, which opens the way for errantry. Goatwalking is errantry that takes the goat-human partnership's adaptation to wild lands as its point of departure.

Adam Huggins 16:18

I had to pause here. Goatwalking seems straightforward enough, but what is "errantry"? I'd only ever heard the word used in the famous novel Don Quixote, so I looked it up. Merriam Webster defines errantry as follows: Errantry is the quality, condition, or fact of wandering, especially a roving in search of chivalrous adventure. If ever there was a man wandering in search of chivalrous adventure, it was Jim. The rest of the preface gets even stranger, but I want you to hear it in full to offer you the same experience that I had reading it for the first time.

Goatwalking 16:57

Errantry is primarily concerned with communion, which in our age focuses on the harmonious adaptation of human civilization to life on Earth.

Goatwalking 17:08

The first decisive step into errantry is to become untamed – at home in wildlands. To be at home in wildlands, one must accept and share life as a gift that is unearned and unowned. When we cease to work at taming the creation, and learn to accept life as a gift, a way opens for us to become active participants in an ancient Exodus out of idolatry and bondage, a pilgrimage that continues to be conceived and born in wilderness.

Goatwalking 17:48

Leisure, solitude, dependence on uncontrolled natural rhythms, alert concentration on present events, long nights devoted to quiet watching. Little wonder that so many religions originated among herders. And so many religious metaphors are pastoral. This dimension of the pastoral experience is as accessible to the Goatwalker, as it was to a pre-industrial shepherd watching the night pass over. Wildlands can wake us to forgotten harmonies, if we return as participants who belong there, rather than as appreciative aliens or subjugating conquerors. As a survival technique, independent of the market economy and land ownership, goatwalking works very well, but is as self-defeating as any other self-centered activity. No one survives for long. As a way to cultivate a dimension of life that's lost to industrial man, goatwalking may put us in touch with a mystery more real than we are.

Goatwalking 19:03

Goatwalking is a book for saddlebag or backpack to live with for a while, casually. It is compact and multifaceted, but for unhurried reflection rather than study. It is woven from stargazing and campfire talk to open conversations rather than to lead the reader on a one way track of entailment to necessary conclusions. I prove no points. This is no teaching.

Adam Huggins 19:36

Okay, so perhaps you're thinking that Jim spent a little bit too much time by himself in the desert. Or perhaps you're put off by the religious phrasing and undertones in this passage. Maybe you're intrigued and want to dive in a little bit deeper. I had all of these reactions, all at once. And since this was the only book that I'd lugged up to the cabin with me in my pack, I just decided to accept Jim's invitation and follow him into the desert. When I emerged several days later, I realized that I'd encountered a truly original thinker, captured within a book that was like no other that I'd ever read. I knew that there must be more to this story. And when I got home, I couldn't really find anything else out there. So I decided to try and tell it myself.

Adam Huggins 20:28

It took me a couple of years and starting a podcast to finally start searching for the right person to help me tell it. First, I got in touch with a local Tucson radio station. And they told me that I had to speak with a man named John Fife. So, I gave him a call. And I was surprised when he picked up after the first ring. I was actually caught a little bit off guard, and so I somehow managed to only record his side of the conversation. Anyway, one of the first things that I asked him was whether all of that stuff about goatwalking was actually true.

John Fife 21:01

Oh, yeah. I mean, that was Jim's iconic way of teaching philosophy. He would teach them desert survival with a goat, go out on these month-long treks, and teach philosophy as he was spending evenings around a campfire and hiking during the day. And he used the desert survival as a kind of metaphor for how one philosophically survives in in an alien and hostile culture.

Adam Huggins 21:36

So it was legit.

John Fife 21:37

Of course.

Adam Huggins 21:38

We ended up talking about their friendship, their disagreements, and where I could find a copy of Jim's second book published after his death.

John Fife 21:47

Everybody who has one has it locked up in a safe somewhere.

Adam Huggins 21:51

No luck there, I guess. And then I mentioned that I was considering a visit to Tucson to spend some time in the desert, and that I'd be honored to meet him and record an interview, if he was willing.

John Fife 22:02

Well, don't get carried away. Before you come down, you need to understand that Jim was the brightest, most intelligent person I have ever met. I was only smart enough to know to pay attention to Jim, right? And not – not get in his way. But if you come down, I mean, the closest people to Jim are Pat and his colleagues at at Saguaro Juniper who lived and worked with him out there after sanctuary.

Adam Huggins 22:34

Pat, you'll remember from the intro was Jim's wife. I asked him if he could put us in touch.

John Fife 22:39

Yeah, sure. I'll just give you her phone number. Her number is --- --- mule, M-U-L-E. I don't know. It's just the way Jim explained it to me and I haven't forgotten. "Oh yeah just call me: --- mule!"

Adam Huggins 22:58

I booked tickets and told John that we'd be in touch.

John Fife 23:01

Okay. Good night.

Adam Huggins 23:07

That October, I was on my way to Tucson. I didn't go down alone though. I was joined by my partner, Ilana, and our friend Teresa. Teresa is originally from Tucson. So she acted as our guide. And Ilana is the kind of person who other people just open up to it helps that she always knows the right questions to ask. But I also think that she has some kind of invisible gravity that just draws people in, and causes them to unburden themselves with her. A dubious gift practically speaking, but for an interviewer, an undeniable asset.

Adam Huggins 23:47

Coming as we were from the Pacific Northwest, the dry heat that greeted us as we stepped out of the terminal in Tucson was a welcome shock to the senses. Outside, the silhouette of a towering saguaro cactus against the star-filled night sky was enough to give this amateur botanist an elevated heart rate.

Adam Huggins 24:10

But Tucson would have to wait. The next morning, we struck out for the small remote town of Cascabel, several hours to the east of Tucson on the beautiful San Pedro River. We have to go speak to a woman about a mule.

Pat Corbett 24:33

Come on Lumpy, come on Nimby, come on Clue!

Soundscape 24:33

[Gate opening]

Adam Huggins 24:37

Lumpy? How do you get a name like lumpy?

Pat Corbett 24:43

[Unintelligible]

Adam Huggins 24:43

I'm sorry [laughs]. Can you say that again? It's short for what?

Pat Corbett 24:49

Lumpen proletariat.

Adam Huggins 24:50

Lumpen proletariat?

Pat Corbett 24:51

Well, when I first got this horse he seemed like such a big lump and he's not actually. He's one of the cleverer horses you'll ever meet.

Pat Corbett 25:01

Come on, Lumpy!

Ilana Fonariov 25:03

I hear the galloping!

Pat Corbett 25:06

Here they come!

Soundscape 25:06

[Sound of galloping in distance as horses approach. Then horse breaths, and the gate closing]

Adam Huggins 25:37

This is Pat Corbett: the woman who taught Ann Russell and the other John Woolman students how to ride horses, and who still keeps and rides horses to this day. But that's not how she started out. For decades, had worked as a librarian.

Pat Corbett 25:52

Well, I'm old enough to have careers for women were not as open as they are now. And so there was kind of a choice between being a nurse, being a teacher, or being a librarian. And I knew I didn't want to be a nurse, and I didn't really want to be a teacher, so that left being a librarian, which I did like – I enjoyed that.

Adam Huggins 26:10

Pat and Jim met when she was 23, and they were both enrolled in library school at the University of Southern California.

Pat Corbett 26:18

Well, I thought he was kind of odd, but the better I got to know him, the more I enjoyed it, obviously, because we ended up getting married.

Adam Huggins 26:26

They ended up being a good match. And they were together until his death in 2001, at the age of 67. Everything that Jim did, Pat would play a major if somewhat unsung role in. Well, almost everything. The goats were definitely more Jim's thing.

Pat Corbett 26:43

I just figured I have a full time job and I wasn't gonna milk goats and that was okay. He didn't mind. I just didn't have Jim's enthusiasm for spending vast amounts of time out sleeping on the ground. When people would ask me if I went goatwalking with him, I'd always just explain that I'd go with him until my supply of ham and cheese sandwiches ran out, then I'd go home.

Adam Huggins 27:07

In many ways, it was Pat's support and practical nature that allowed Jim the freedom to roam the desert for weeks on end.

Pat Corbett 27:15

People would say "Oh, what does your husband do?"

Pat Corbett 27:18

"Well, let's see. I guess you could say he's a goatherd, philosopher cattleman", and I'd get this very strange look.

Adam Huggins 27:28

So what exactly is a goatherd philosopher? Well, on its face, it's quite simple. Jim was a philosopher and he spent a lot of time with goats. To go deeper, you have to be willing to spend some time with his first book Goatwalking, which takes some decoding. It's dense with references to Don Quixote, the Torah, Chung Tzu, and Henry David Thoreau – equal parts survival handbook, memoir, religious text, and philosophical treatise. Jim draws liberally from Buddhism, Taoism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Quakerism, which means you have to be willing to adapt to the idiosyncratic use of religious language in his writing. But at Goatwalking's core is a simple message, captured beautifully in the subtitles that mark its first chapter:

Goatwalking 28:21

Going out; Doing nothing; Getting nowhere; Losing hold.

Adam Huggins 28:28

It asks us to put aside our bottomless need for productivity and entertainment, and to try – even for just a short time – to be at home in wildlands. You could do this any number of ways. And for Jim, goatwalking was his portal. It was a way to become feral for a time in a society that all but makes this impossible.

Goatwalking 28:50

Goatwalking happens to be the easiest way I know to feed myself by fitting into an ecological niche, rather than a social hierarchy. It also happens to be the only way I've discovered to share and bequeath the outlook and practice of symbiotic covenanting with a technocratic society.

Adam Huggins 29:13

For Jim, covenanting is a social activity whereby a community fulfills its sacred obligation to wildland communities to protect, care for, and hallow them. Hallow – as in to honor as being holy. You know: "Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name" – words which are imprinted in my head from years of Bible school. But for some reason, despite my deep, reflexive mistrust of this religious language, which I associate with personal feelings of betrayal, Jim's writing casts these words in a different light.

Goatwalking 29:50

Goatwalking is errantry that is primarily concerned with opening a way through adversities faced by any people that covenants to treat no one as an inferior, enemy, or alien. To choose freedom is to cease collaborating with organized violence, but ceasing to collaborate means errantry of one kind or another. In the eyes of Pharaohs and slaves, it means straying out into the desert.

Adam Huggins 30:22

Right there, next to that biblical reference to the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, there's that word again: Errantry. It's not remotely biblical. As I've said before, it's a reference to Don Quixote, who fashioned himself a knight errant: a man who wanders in search of adventures and opportunities to prove his chivalry. For Jim, who wandered errant in the desert with his goats, ruminating on ways to live non-violently in a technocratic society, the irony that Don Quixote was tilting at windmills was not lost.

Goatwalking 30:58

Errantry mean sallying out beyond the society's established ways, to live according to one's inner leadings. This looks like, and in a sense is madness – Quixote's madness. Both the lunatic and the visionary create a life outside the ready-made roles prescribed by their society.

Adam Huggins 31:24

Prophets, mystics, and fools all seem to merge from the margins of history – from the desert. And it can be hard sometimes to tell them apart. Impossible, perhaps, if their resolve is never tested.

Adam Huggins 31:41

As it happens, though, Jim would find himself tested in a way that few of us will ever be. But in order to fully appreciate the story I'm going to tell in this series, I think it's important to understand just how Jim came to be a goatherd philosopher cattleman. Because this man that I have become fascinated by, who would go on to do such extraordinary things – I don't really want to put him on a pedestal. He was just a man. And many people stood beside him during his trials, both literal and figurative, some of whom I speak to in the series, and some of whom will go unnamed. He was in some senses extraordinary, and in others, just ordinary. But there is a quality that I think makes him stand out from most of the rest of us. If we're being honest with ourselves.

Pat Corbett 32:33

It was, I guess, so apparent right from the start that he marched to his own drummer, and if he thought something was wrong, he just did it.

Jim Corbett 32:45

I grew up - let's see, I was born in 1933 and grew up in and around Casper, Wyoming.

Adam Huggins 32:53

This is Jim's voice captured in a series of tapes by journalist Miriam Davidson in the mid 1980s. Aside from a few videos that I was able to dig up, these tapes, which Ms. Davidson and the University of Arizona have generously shared with me, are the only recordings that I have of Jim, and as a result, you'll occasionally hear Ms. Davidson interjecting in the conversation. Jim grew up in the conservative culture of depression-era Wyoming, but his parents were educated and worldly. His father had been a lawyer in the Ozarks, but had lost some of his eyesight in a car accident and had to support his family, with three children, on a teacher's salary, which wasn't very much in those days. To supplement, they'd live off the land at times.

Jim Corbett 33:39

You know, we lived out a lot. We'd go out just – virtually all the meat we ate, and we ate a lot of meat because it was the cheapest, easiest thing was, you know, deer, moose, elk, and so forth. And then, during the summer vacation, we would simply take a tent, and move up into the Tetons and live up there.

Miriam Davidson 34:00

Wow must have been fun!

Jim Corbett 34:02

Yeah, it was good. But it was a very independent kind of life.

Adam Huggins 34:07

Jim came by his love of wildlands honestly. He must also have inherited some of his deep personal convictions from his father.

Jim Corbett 34:15

My father had a very strong sense of justice, a strong social conscience.

Adam Huggins 34:23

His lifelong fascination with religions, however, doesn't appear to have come from either parent.

Jim Corbett 34:28

I can remember, when I was nine years old, I learned about the Baptist and they said, they can fix it up so I'd live forever, and that sounded like a good idea. And so I started attending church. I can still remember at one point all full of myself, coming back home and telling my mother that when I grew up I was going to be a preacher. She looked at me, and she said "Well, you'll get over it" [laughs].

Adam Huggins 34:56

In some ways, he did, and in some ways, he didn't. His mother's cynicism about religions apparently did rub off on him though, because he quickly dispensed with Christianity and its extravagant promises of life after death. He never did become a preacher. But he did form a deep, lifelong friendship with a man who did. A man that I've already introduced you to.

Adam Huggins 35:20

Good morning,

John Fife 35:22

I'm John.

Adam Huggins 35:22

Adam.

John Fife 35:23

Adam?

Adam Huggins 35:24

Nice to meet you at long last!

John Fife 35:25

Well, welcome.

Adam Huggins 35:26

After meeting Pat in Cascabell, we returned to Tucson and met up with John Fife at Southside Presbyterian Church. Whereas Pat shared Jim's economy with words, John was gregarious and welcoming. And Southside itself was beautiful, with an inclusive circular worship area that was far removed from the pew and pulpit chapels of my childhood. We took a seat in his office and picked up right where my phone conversation with him had left off.

John Fife 35:55

Jim grew up on a sheep ranch in Wyoming. And everybody recognized – folks I've talked to from his childhood – everybody recognized he was smarter than everybody else in Wyoming.

Adam Huggins 36:11

When it came time for Jim to graduate high school, it was clear that he needed to look beyond Wyoming. For his undergraduate, he went to Columbia University on a full scholarship, graduating in just three years with a perfect 4.0 GPA. Up next was an invitation from Harvard to get his master's in philosophy.

John Fife 36:30

And I've talked to guys who were in Harvard with him and they said "Oh, yeah, Corbett was a smartest guy. We knew. And there was a big gap between Corbett and the second and third smartest guys in the class". So it was obvious.

Adam Huggins 36:45

Jim Corbett: a goatherd with a master's in philosophy. But the goats would come later. Right after graduating from Harvard, Jim volunteered to be drafted into the army. His justification?

Jim Corbett 36:58

Well, I was drafted – in fact, I volunteered for the draft. And I just grew up thinking once you get to that point, you're going to be drafted, might as well get it over with.

Adam Huggins 37:08

This was the mid 1950s, before Jim discovered Quakerism, and not long after the Second World War and the Korean War. Coming from Wyoming, Jim was raised at a time and place where serving was viewed as an inevitability for young men. But as you might have guessed, the army was not a great place for someone who marches to the beat of their own drum,

Jim Corbett 37:30

I was drafted into the army. And because my commanding officer considered me a demoralizing influence –

Miriam Davidson 37:37

And why did he say that?

Jim Corbett 37:38

Oh, I just – I was.

Miriam Davidson 37:40

How so?

Jim Corbett 37:41

I just did everything that kind of showed I didn't have the proper respect and discipline, but not in ways where they could actually –

Miriam Davidson 37:50

You mean your shoes weren't shined and your hair wasn't combed?

Jim Corbett 37:52

Yeah all that sort of thing.

Miriam Davidson 37:53

That's funny.

Jim Corbett 37:54

So anyway –

Miriam Davidson 37:56

I wonder and you weren't afraid of what they would do to you or...?

Jim Corbett 37:59

Oh, yeah, I tried to avoid...You know, I'm fairly good at being out of the way when they swat [laughs].

Adam Huggins 38:07

During his stint in the army, Jim married a girl named Mary Lou from his hometown of Casper, Wyoming. And they had three unplanned children just before and after he was discharged. The marriage only lasted five years. And in the end, Mary Lou left without warning and took the children with her. Jim, just entering his late 20s, was suddenly adrift.

Jim Corbett 38:31

Yeah, I went through a kind of controlled nervous breakdown: wandered around, went off to Berkeley for a while – holed up there, reading nothing, virtually nothing, for a while, but Bahasa Indonesia.

Miriam Davidson 38:47

What?

Adam Huggins 38:48

I had to look this up Bahasa Indonesia is a standardized version of Malay that is spoken in Indonesia. During his time in Berkeley, Jim would just go back and forth to the library, checking out books in Bahasa Indonesia. He settled into a pretty deep depression.

Jim Corbett 39:05

I was turned around, you know. Self absorption kind of reached a point of committing suicide, I guess.

Adam Huggins 39:15

In Goatwalking, Jim writes about this moment,

Goatwalking 39:19

Sitting in the cheapest room I could find in Berkeley, I often concentrated on my heartbeat. When I concentrated on it, the stillness expanded and each beat became a sudden clutching – to keep from slipping away into final stillness. Each beat let me know that my heart still cared enough to clutch for life. As caring withered, the stillness grew, and the clutching weakend.

Goatwalking 39:51

Late one night, as I sat waiting with indifference for each next beat of my heart, I realized that it was slowing much more than ever before – to a stop. The last strands of caring gave way. I let go.

Goatwalking 40:17

Out of the stillness that I thought was death, love enlivened me. Or something like love that doesn't split, the way love does – into loving and being loved.

Jim Corbett 40:30

And it was at that time that when I kind of put my personality back together again, I had the reorientation that made me decide that must be a Quaker, from what little I knew about them, and I looked up the meetings.

Adam Huggins 40:52

For those unfamiliar with Quakerism, it's a non violent religious movement that branched out from Protestant Christianity. Only a small percentage of Quakers participate in the kind of meeting that Jim is describing, though. In these meetings of friends, Quakers will worship by sitting in silence with one another. If any person is moved to provide testimony, then they simply do. Otherwise the affair is silent. For Jim, the stillness of love that doesn't split, the stillness of the Quaker meeting, and the stillness of the desert would become his spiritual Foundation – one that he could return to, over and over.

Adam Huggins 41:40

A lot happened in Jim's life between his time in Berkeley in the early 60s, and his goatwalks with the John Woolman school in the late 1970s. He studied to be a librarian met and married Pat. And unsurprisingly, he spent a good deal of time during the Vietnam War in the 1960s as an anti war activist, specifically targeting young draft aged men, like he had been a decade before and encouraging them to become conscientious objectors. But two other things happen during this time that are worth noting. The first is that he was suddenly struck by a mysterious autoimmune disease,

Jim Corbett 42:19

It attacked bodily organs caused swelling of muscles. There were quite a few different symptoms. And it was diagnosed as being one of dermatomyositis periarteritis nodosa, or systemic lupus erythematosus. The diagnosis actually, that had come when I was at the University of Oregon, was one where it seemed unlikely that I live more than a year or so. So you know, it was a fairly severe kind of situation.

Adam Huggins 42:51

This unknown, debilitating shape shifting sickness preyed on Jim for several years, as he worked as a librarian at post-secondary institutions in Oregon, Arizona and California. Pat wasn't at all sure that he was going to survive.

Pat Corbett 43:06

But then eventually, and this was some years later, we moved over to California, so he could go to the UCLA Medical Center, and the doctors out there said "Well, I don't know what you had before. But I tell you what you have now: you have rheumatoid arthritis", which, you know, it sounds kind of awful. But we kind of celebrated that diagnosis, because it was better than the alternatives.

Adam Huggins 43:27

Jim would live. But for the rest of his life, his hands and feet would be visibly contorted, and he would experience near constant pain. Ann noticed this during her time with Jim on the goatwalk.

Ann Russell 43:40

He was in pain a lot. But he just – he said you just sort of notice it, and then kind of put it away. You're never unaware of it, but you don't let it dominate.

Adam Huggins 43:54

Although he might not admit it. The pain gave him a resolve that allowed him to continue on ahead when others would have been discouraged.

Jim Corbett 44:02

I guess it made it so that I always feel a lot more grateful about still being alive, if that's about it.

Adam Huggins 44:10

Even as he managed to continue working despite his illness,he second thing that happened during this period was that he just kept getting fired for taking stands on things. First, he lost his job at Cochise College in Arizona, because he insisted on defending a decidedly unpatriotic piece of artwork on exhibit there. It was an issue of freedom of speech. And then, after taking a position at Chico State in California, he took a stand on academic freedom. It was 1969, and there were widespread protests and a strike all across the California State system. But Jim wasn't interested in any of that.

Jim Corbett 44:49

It was kind of traditional left wing stuff with lots of slogans and raised clenched fists and all that kind of stuff, and without in my opinion, the kind of respect for truth that one needs. That is, all of the these faculty members at that time that were getting involved in protest had to identify themselves as an oppressed class of some kind. And coming from having lived much of my life cowboying, sheepherding, and whatnot, I didn't see a lot of oppressed people on the faculties of the California State system. And I thought it was a lot of nonsense. So I wasn't involved in the traditional left wing stuff, and I couldn't stand their meetings. In any case, so I was actually fired for holding a one person strike [chuckles].

Adam Huggins 45:47

I find this piece of tape so revealing. The actual details of the issue are tedious. Jim objected to the firing of another faculty member and tried to right the issue internally, before eventually writing some incendiary things in a local paper. But the fact that in this time of intense political turmoil and social change, Jim had honed in on a perceived wrong that everybody else was overlooking, and it taken a lonely stand with really nothing to gain and plenty to lose personally. It's a recognizable pattern.

Adam Huggins 46:27

After Chico, Jim and pat moved back to Arizona, and Jim spent a lot of time doing the things that came most naturally to him. ranching, herding and activism. It's during this period in the 1970s, when he would develop this practice of goatwalking

John Fife 46:42

Jim's a rancher – by history, by all he learned growing up about how a herd relates to the land, and all of those interactions and all of the relationships that that you need to understand for the... for both the land and the herd, and the person who's the herder and how that interaction sustains and grows, the whole ecology of all of those relationships. And he put all of that together from from probably his earliest years, but continued it his whole life. It's an incredible gift that he brought to the land and to the desert here. And his unique quest to figure out how one survives in an extreme ecology, like the Sonoran Desert, with what the desert provides, and one goat for nutrition, right? He figured all of that out quickly. And then practiced it – Practiced it and practiced it with groups of students he brought to the desert on desert treks, while he taught them desert survival with that one goat, which is why he called it goatwalking. And then use that experience to help them understand what they have just experienced as a metaphor for how one survives with integrity and faith, in the midst of a toxic culture, which, which tries to destroy everything ecologically and humanly. And so it was... it was pure genius in practice.

Adam Huggins 47:45

This practice of errantry, or sojourning, feral into the wild lands. It's an ancient spiritual practice. But Jim discovered a unique way to practice and teach it in the modern era that has few, if any analogues. I've personally spent many, many hours milking goats, and a good deal of time walking with them as well. I've also spent many days and nights out in wildlands. I've even done a couple of 10-day silent meditation retreats, which were some of the most challenging days of my life. But putting all of this together, I keep trying to imagine the kind of freedom of thought, of movement, experience, and revelation that Jim's practice of goatwalking might offer. It's the reason that I went down to Tucson, and it's also the reason that I return to goatwalking over and over again: to bathe in the wisdom and ideas born of those desert nights.

Adam Huggins 49:54

And Jim's ideas were about to be put to the test.

John Fife 50:00

When we started to be aware of the repression, and the death squads, and the torture, and the persecution of the church – the gunning down of the Archbishop, the killing of 17 priests. A Catholic priest and I, who had been doing a lot of social justice work together in the barrio here, said, you know, we need to make sure people here are aware of the repression in El Salvador for people of faith. And Jim came to me at that point, and said, "John, I don't think we have any choice under the circumstances except to start smuggling refugees safely across the border. So they're not caught by Border Patrol or immigration authorities". And I basically said "really, how do you figure that Jim?"

Pat Corbett 50:55

I mean, that was the kind of thing he did, you know. If he came involved in something that he thought was important, and needed something done about that he might be able to do, then he was very likely to go do it or try and do it.

Ilana Fonariov 51:09

So were you prepared for how quickly all of this would have happened?

Pat Corbett 51:13

No, I didn't have a clue. Somehow it just came upon us. If you're around Jim, things like this would happened. And then somehow you just sort of took it for granted.

Adam Huggins 51:30

You know, we never got you to do we never got you to introduce yourself and tell us your name and where you are.

Pat Corbett 51:37

Well, my name is Pat Corbett, and I was married to Jim Corbett, who was one of the folks responsible for starting the Sanctuary Movement.

Adam Huggins 51:45

That's next time – on part two of Goatwalker.

Adam Huggins 52:14

Goatwalker is produced by myself, Adam Huggins and Mendel Skulski, for Future Ecologies.

Adam Huggins 52:20

For photos, citations and more information about the people and events described in this series, please visit futureecologies.net.

Adam Huggins 52:28

In this episode, you heard Ann Russell, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Jim Corbett, and Miriam Davidson. Narration by Phillip Buller.

Adam Huggins 52:39

Music was by Hidden Sky, People with Bodies, Ben Hamilton, and Sunfish Moon Light. The Goatwalking Theme is by Ryder Thomas White and Sunfish Moon Light.

Adam Huggins 52:52

Special thanks to Ilana Fonariov, Teresa Maddison, Susan Tollefson, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Nancy Ferguson, Tom Orum, Gary Paul Nabhan, Gita Bodner, Amanda Howard and the University of Arizona, Charles Menzies, Sadie Couture, Phil Buller and Jan Adler, Michael Smith and Cathy Suematsu, and Danny Elmes.

Adam Huggins 53:21

Future Ecologies is an independent production, supported by our Patrons. To join them go to patreon.com/futureecologies.

Adam Huggins 53:29

This series was recorded on the territory of the Tohono O’odham, and produced on the unceded, shared, and asserted territory of the Penelakut, Hwlitsum, Lelum Sar Augh Ta Naogh, and other Hul’qumi’num speaking peoples. It's important to acknowledge that the public lands that Jim would walk his goats on are also stolen Indigenous lands, as are the lands that we produce this podcast on.

Adam Huggins 53:54

Thank you for listening and see you next time.