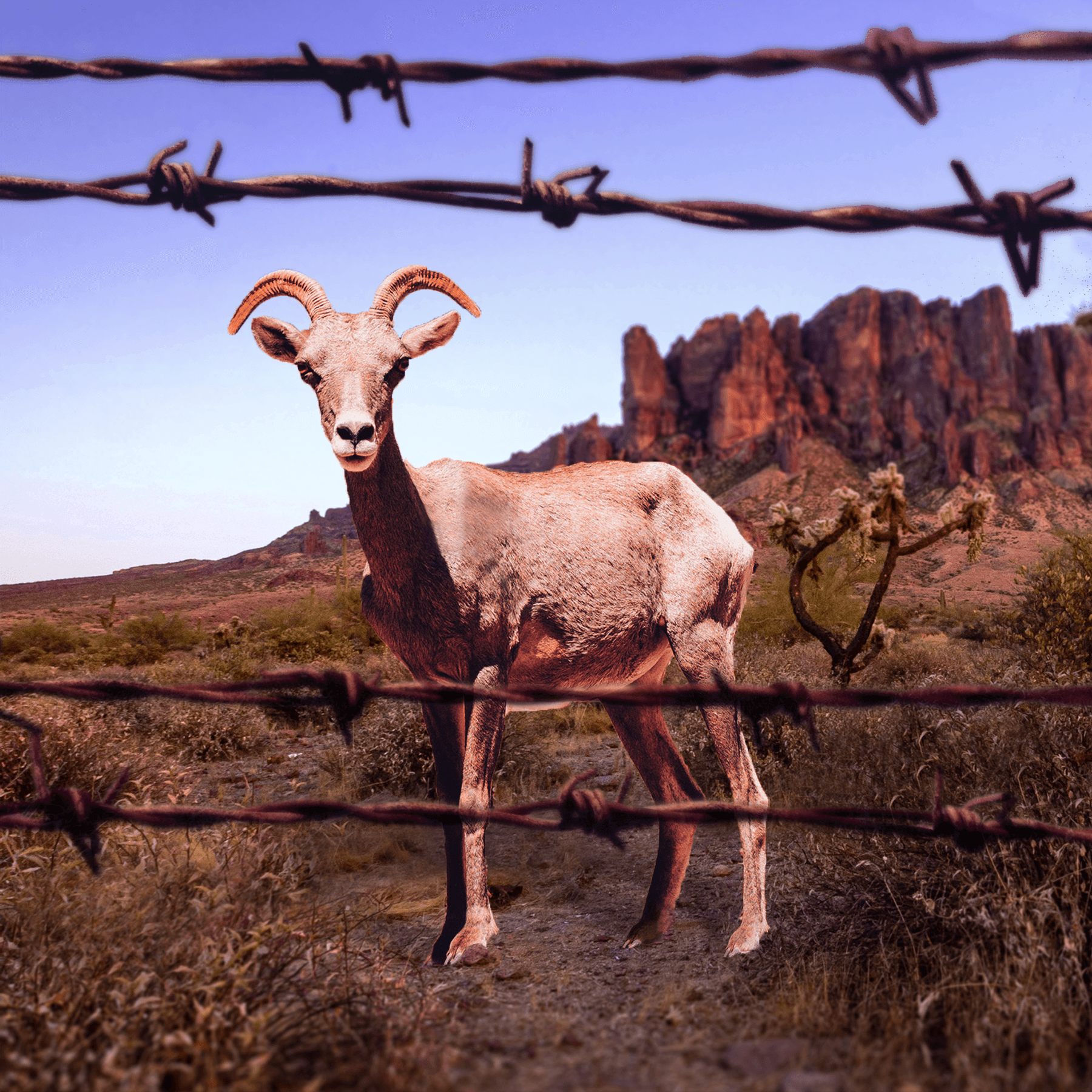

Collage of images by Call Me Fred, Brad Fickeisen, and Logan Mayer.

We suggest you start with Part 1 of this series.

Summary

In the early 1980s, the outbreak of civil war across Central America forced unprecedented numbers of refugees to seek asylum in the United States, putting the recently passed 'Refugee Act' of 1980 to the test. There was just one catch: the Reagan Administration was providing funding to right-wing governments that most of these refugees were fleeing. As a result, Central American refugees making the dangerous journey to the U.S.-Mexico borderlands were being intercepted, denied asylum, and summarily deported.

As this crisis unfolded, a ragtag group of self-proclaimed 'goatherds errant', led by philosopher-turned-rancher Jim Corbett, took it upon themselves to enact U.S. immigration law at the grassroots level. In so doing, they sparked a national movement that continues to the present day, turning the concept of 'civil disobedience' upside-down.

From Future Ecologies, this is Goatwalker, Part Two: Sanctuary.

Ready for Part 3? Click here.

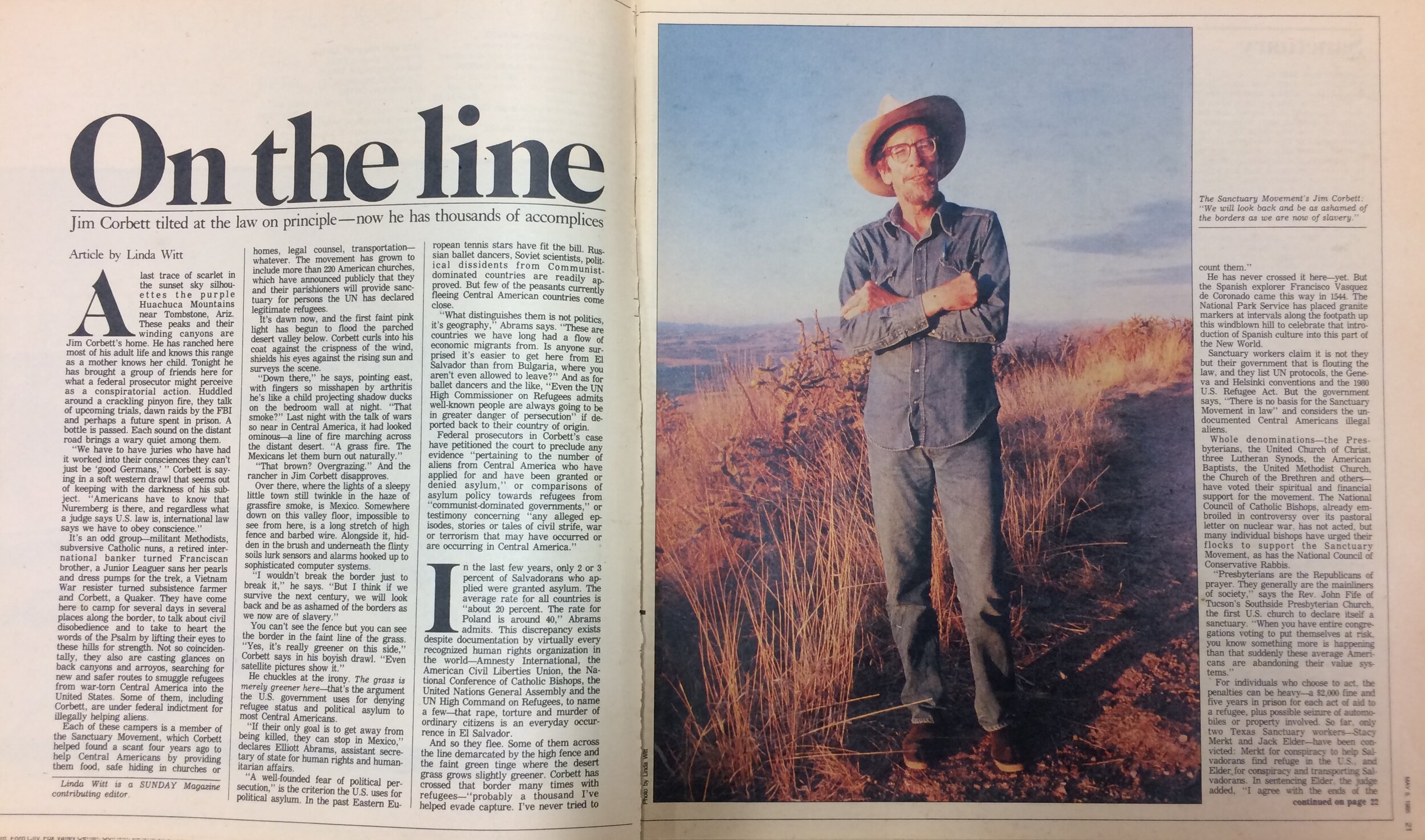

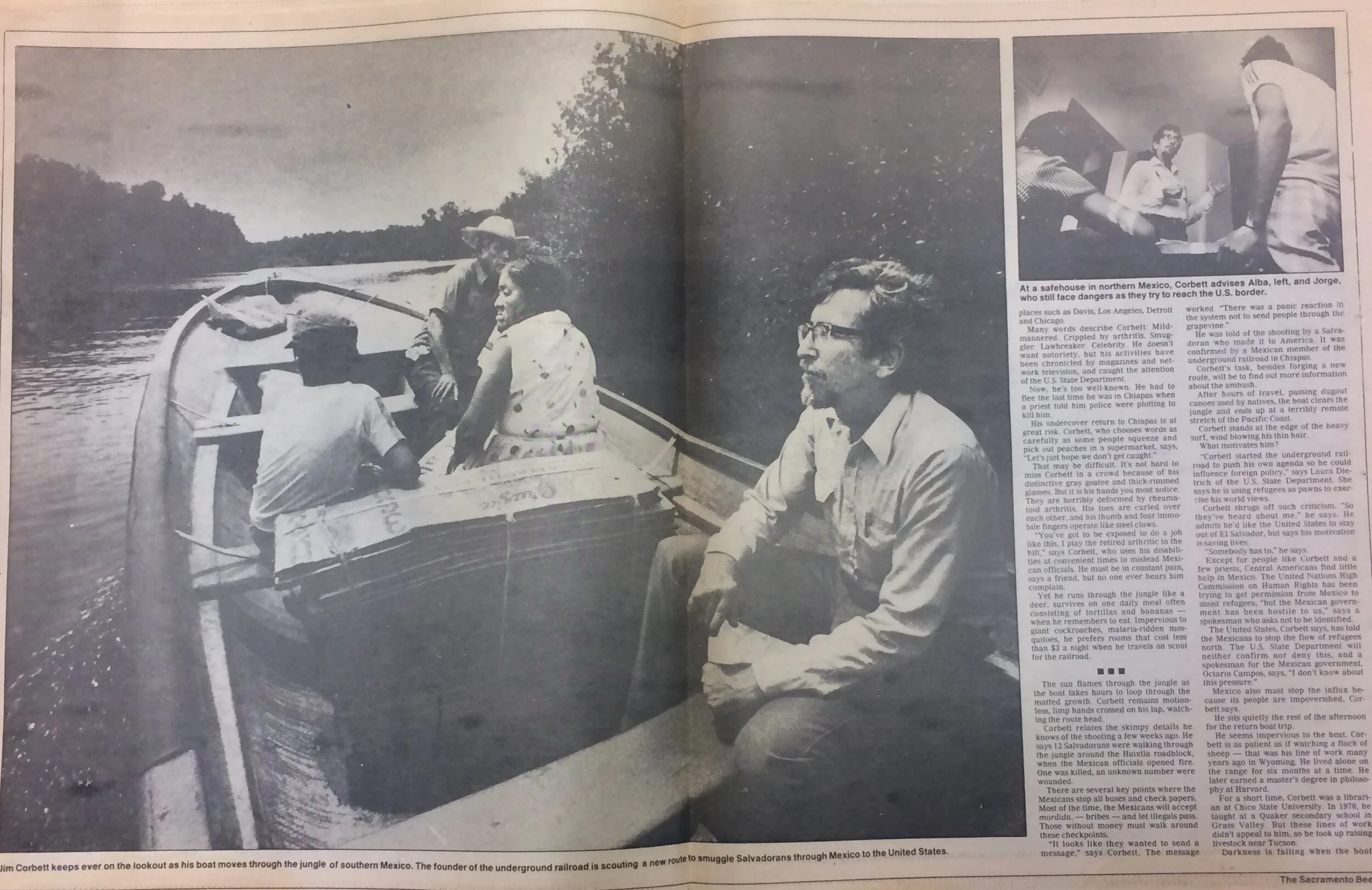

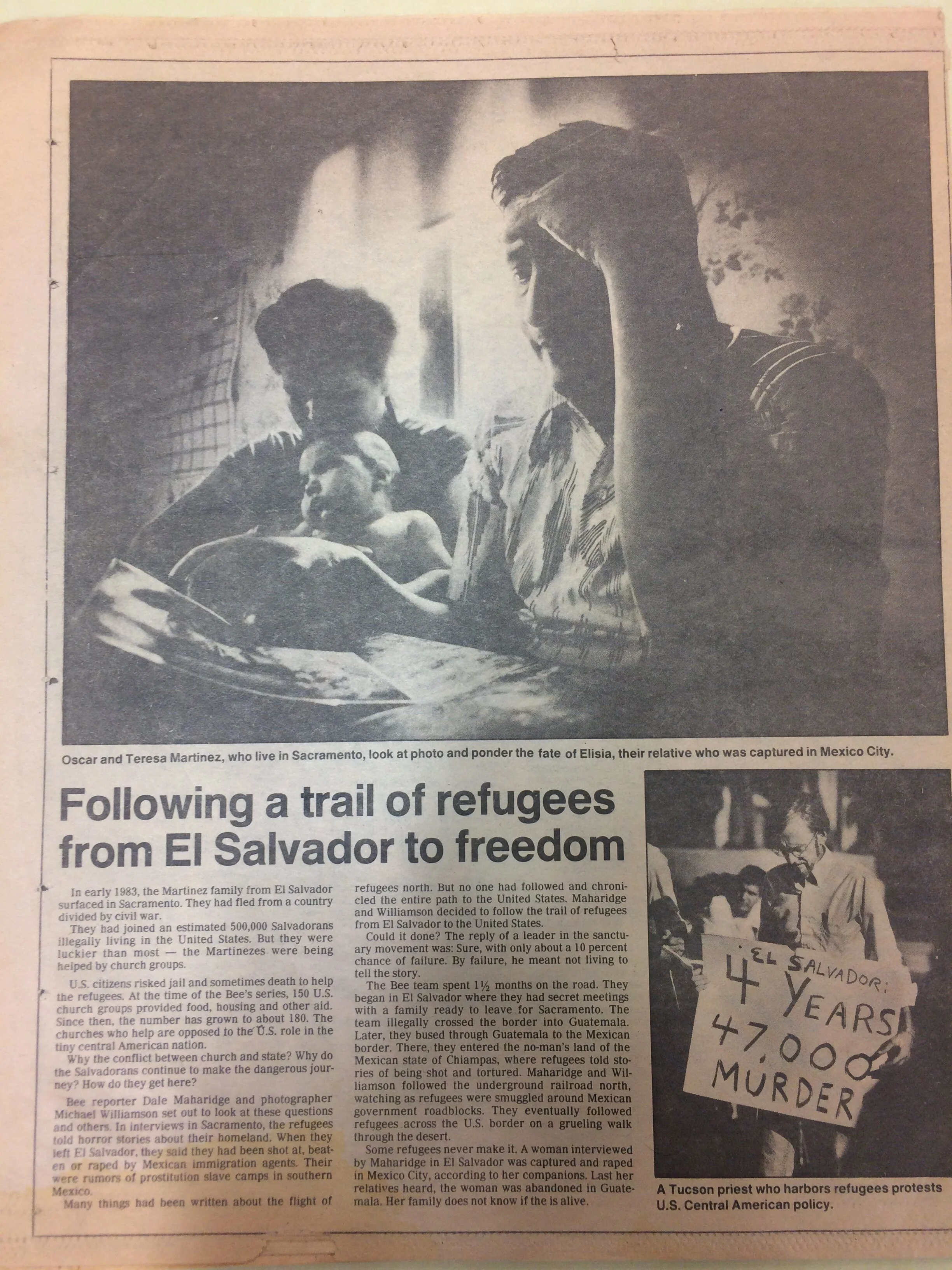

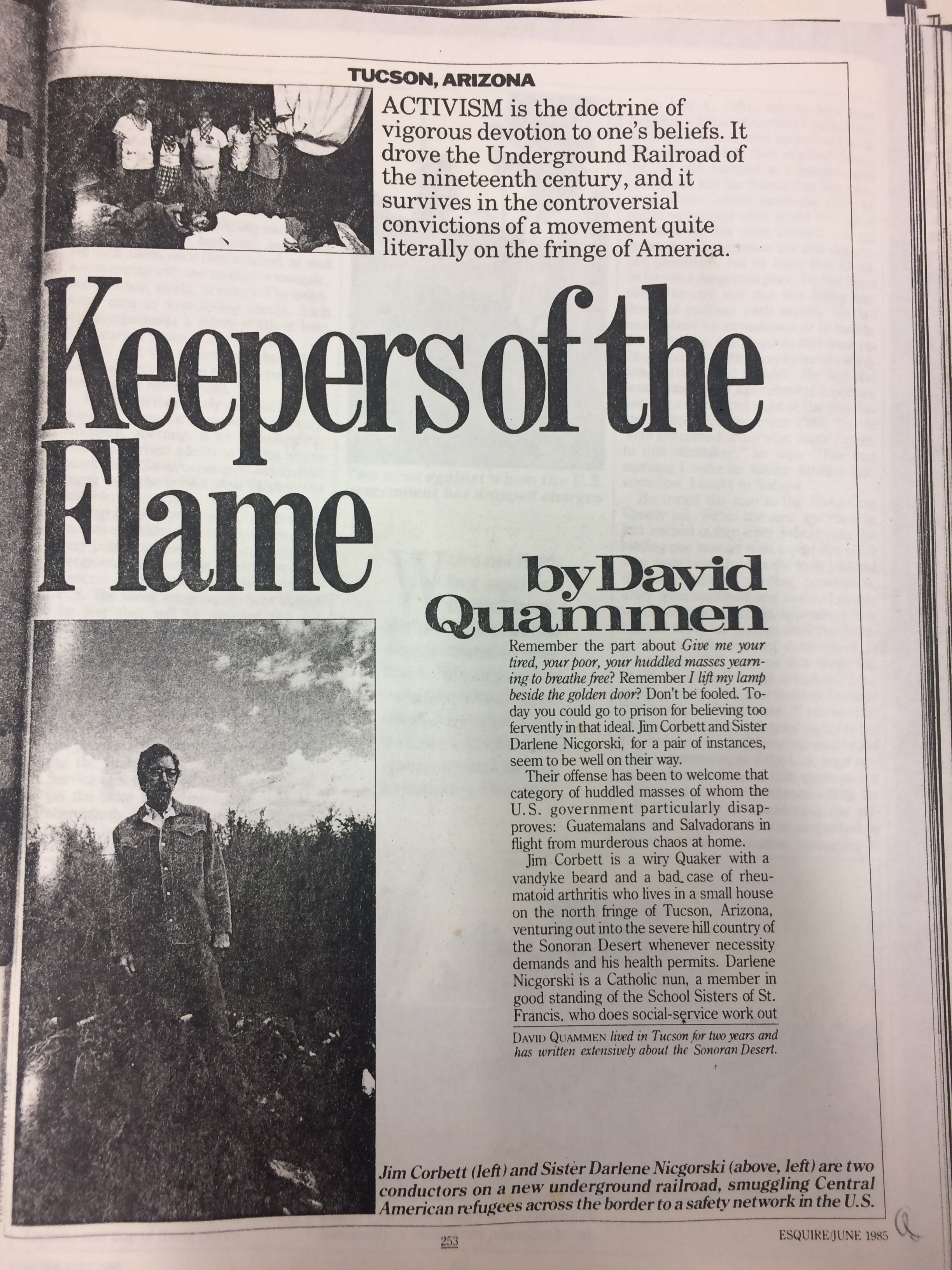

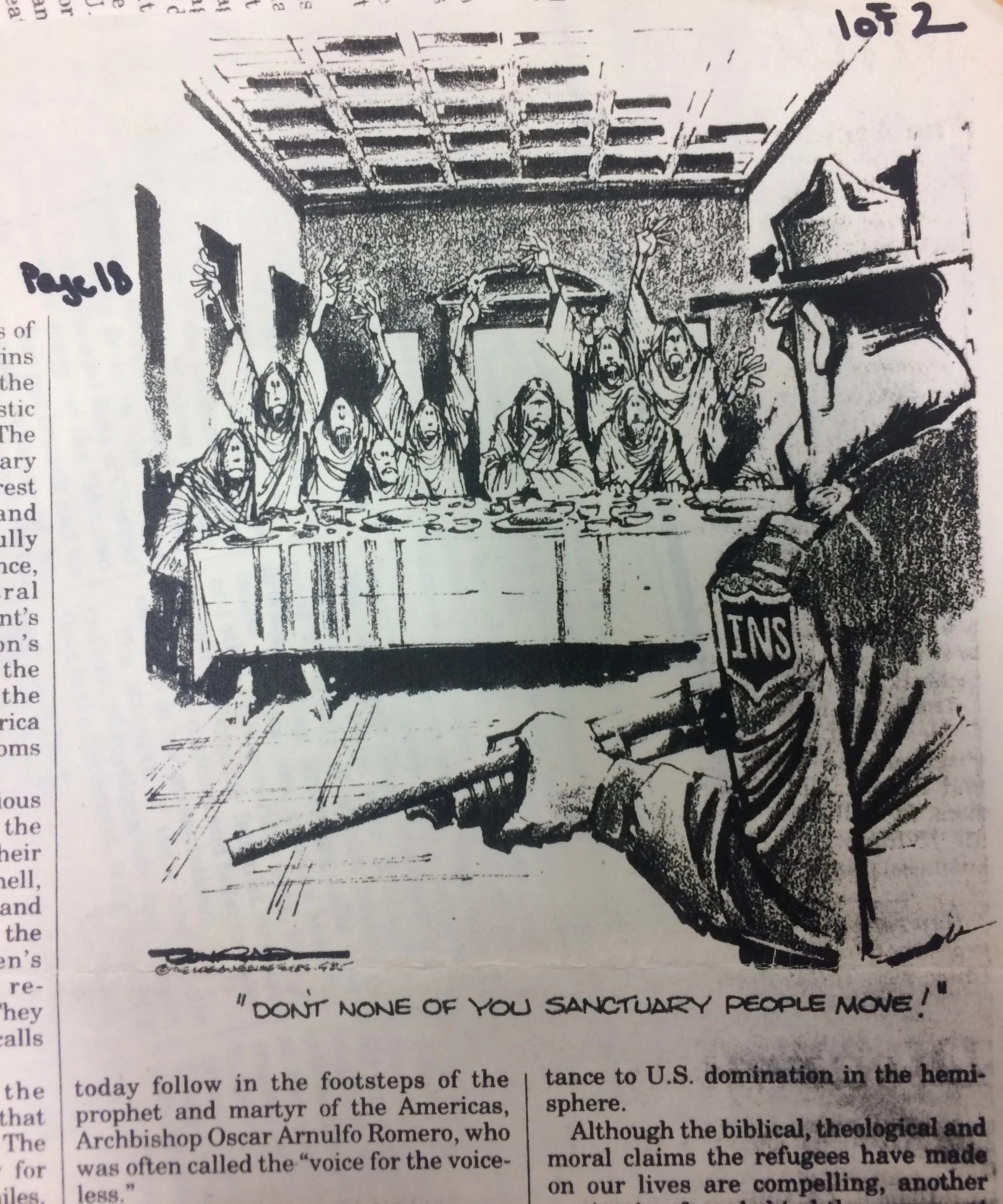

A selection of news clippings on Jim Corbett and the Sanctuary movement

from the University of Arizona archive

Show Notes

This episode features Ann Russell, Tom Orum, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Gary Paul Nabhan, Jim Corbett, and Miriam Davidson. Narration by Phillip Buller.

As of August 2021, Jim Corbett’s books, both “Goatwalking” and “Sanctuary for All Life” have been re-issued as new 2nd editions, with paperback and e-books available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Find photos of Jim on his memorial page with Saguaro Juniper

Music by Hidden Sky, People with Bodies, Meteoric, and Sunfish Moon Light. Goatwalking Theme by Ryder Thomas White and Sunfish Moon Light.

This episode was produced by Adam Huggins and Mendel Skulski.

Hear also:

Special thanks to Ilana Fonariov, Teresa Maddison, Susan Tollefson, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Nancy Ferguson, Tom Orum, Gary Paul Nabhan, Gita Bodner, Amanda Howard and the University of Arizona, Charles Menzies, Sadie Couture, Phil Buller and Jan Adler, Michael Smith and Cathy Suematsu, and Danny Elmes.

This series was recorded on the territory of the Tohono O’odham, and produced on the unceded, shared, and asserted territory of the Penelakut, Hwlitsum, Lelum Sar Augh Ta Naogh, and other Hul’qumi’num speaking peoples. It’s important to acknowledge that the public lands that Jim would walk his goats on are also stolen Indigenous lands, as are the lands we live on.

This episode includes audio recorded by Nosebleed Cinema and deleted_user_7146007, protected by Creative Commons attribution licenses, and accessed through the Freesound Project.

Citations

Corbett, J. (1992). Goatwalking. Penguin Books

Davidson, M. (1979). Miriam Davidson papers. University of Arizona Libraries, Special Collections (MS 433)

Davidson, M. (1988). Convictions of the Heart. Univ. of Arizona Press

West, M., et al (2017, June). The Valley View #6 (Cascabel Newsletter)

Witt, L. (1985, May 5). On The Line, Chicago Tribune Sunday Edition

You can subscribe to and download Future Ecologies wherever you find podcasts - please share, rate, and review us. We’re also on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and iNaturalist.

If you like what we do, and you want to help keep it ad-free, please consider supporting us on Patreon. Pay-what-you-can (as little as $1/month) to get access to bonus monthly mini-episodes, stickers, patches, a community Discord chat server, and more. This season, we’re taking a tour of some of our Seaweed Sojourners, with the help of Josie Iselin.

Future Ecologies is recorded and produced on the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the WSÁNEĆ, Penelakut, Hwlitsum, and Lelum Sar Augh Ta Naogh, and other Hul'qumi'num speaking peoples, otherwise known as Galiano Island, British columbia, as well as the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the Musqueam (xwməθkwəy̓əm) Squamish (Skwxwú7mesh), and Tsleil- Waututh (Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh) Nations - otherwise known as Vancouver, British Columbia.

Transcription

Introduction Voiceover 00:01

You're listening to season three of Future Ecologies.

Mendel Skulski 00:07

Hello, and welcome to part two of Goatwalker. In the last episode, we met Jim Corbett, a rancher, philosopher, and desert survivalist. If you haven't already heard it, I strongly suggest you give it a listen. Because understanding a bit about Jim will go a long way towards understanding the radical social movement he helped to spark.

Mendel Skulski 00:30

The story of that movement is the subject of today's episode. My co host, Adam will take it from here.

Adam Huggins 00:46

So what comes to mind when you hear the word sanctuary?

Adam Huggins 00:59

For me, up until just the past few years, the word would have conjured images of this scene of Quasimodo rescuing Esmerelda in the Hunchback of Notre Dame, Disney version, of course. Sanctuary has almost a medieval feeling as if it's a historical artifact of a bygone time. But by around 2016, the word sanctuary had assumed an entirely new meaning, at least in the United States. At the time, the status of so called sanctuary cities was getting a lot of press. driven by a former reality TV show star turned politician.

Donald Trump 01:40

We will end the sanctuary cities that have resulted in so many needless deaths.

Adam Huggins 01:51

If this somehow flew under your radar, sanctuary cities are basically jurisdictions that pledged to offer municipal services and conducts law enforcement without cooperating with immigration enforcement. Meaning, theoretically, that if you were living in a sanctuary jurisdiction in the United States without legal status, you could still access housing or legal services and interact with law enforcement without fear of deportation. By 2018, over 500 US jurisdictions had adopted some kind of sanctuary policy. The Trump administration made several attempts to fulfill a campaign promise to withhold federal funding from these self identified sanctuary cities. But like most things the Trump administration tried to do. Their attempts to cut this federal funding got bogged down in the courts and eventually blocked, in whole or in part, depending on the provision. Underneath all of this noise, you might be wondering how this idea of sanctuary made the jump from the Abbey's of medieval Europe to the supercharged rhetoric of US immigration policy sanctuary

Donald Trump 02:56

For these criminal illegal aliens.

Adam Huggins 03:01

Thankfully, for nearly every question like this nowadays, someone has produced a podcast to answer it. And in 2017, producer Delaney Hall of the podcast 99%, Invisible, released a two part series profiling something called the Sanctuary Movement, and organizing network of churches and civil society groups that formed in the 1980s to help refugees from Central America evade US immigration authorities. The series focused specifically on the church state issues this movement raised, and on the eventual trial of its leadership, chief among whom were John Fife, and Jim Corbett.

Adam Huggins 03:42

The 99% Invisible series puts the spotlight on John, which makes sense, he remains a powerful voice in defense of migrant rights. And of the two men, he's the one who's still able to sit for an interview. But for me, this has the unintentional effect of downplaying Jim's foundational role in the movement. In fact, when Jim suddenly started relating his experiences as part of the Sanctuary Movement, about halfway through Goatwalking, his first book, I actually had to go back and listen to the 99% Invisible story to see if he was in there at all – because if he was, it hadn't really left an impression. It turns out they had included him, but I could be forgiven for forgetting, other than some details surrounding the decision to declare sanctuary and the trial. This is how producer Delaney Hall summed Jim up at the time.

Delaney Hall 04:34

Jim Corbett died in 2001. But back in the 80s, he lived on the edge of Tucson, he raised goats, and he knew a lot about philosophy. He was also a Quaker.

Adam Huggins 04:46

Now, don't get me wrong. She definitely had Jim pegged. He did raise goats and was a Quaker and he knew a lot about philosophy. The series is excellent. I highly recommend listening to it and I think she made the right call and not getting too deep into the weeds with Jim.

Adam Huggins 05:05

But on this podcast, getting into the weeds is what we're all about. And in my estimation, Jim's philosophy and his goat walking aren't incidental to the story of the Sanctuary Movement. They're essential, and they prefigure everything that follows. All of his life, Jim had been tilting at windmills, seeking opportunities to live out his philosophy of errantry and nonviolence in practice. And in the early 1980s, Jim finally picked a windmill that turned out to be a lightning rod. All it took was a chance encounter. From Future Ecologies, this is Goatwalker, part two: Sanctuary.

Adam Huggins 06:00

The origin story of the Sanctuary Movement in the United States might begin with a small goat milking cooperative that Jim Corbett had brought together in the early 1980s. Jim and his wife, Pat, we're living in Tucson, Arizona, and Ann Russell, the Quaker student who went on a goatwalk with Jim in the 1970s happened to be attending the University of Arizona at the time.

Ann Russell 06:24

I started my master's degree, and they were living close by. And so I started to go over because I missed the goats and I missed Jim, and I would go over and milk in the morning, and he would make oatmeal. And the three of us would have breakfast,

Adam Huggins 06:39

Ann was working in the department of plant pathology when she met Tom Orum. And it didn't take long for her to introduce Tom to Jim and the goats.

Ann Russell 06:48

And so he started coming over and the group started getting bigger and then it was a goat co-op.

Adam Huggins 06:54

The members of the goat co-op jokingly referred to themselves as Los Cabreros Andantes.

Ann Russell 07:01

Jim read Don Quixote, he saw himself as Don Quixote, and in Spanish, a knight errant, which was what Don Quixote was – in Spanish, that's Caballeros Andante. So we were Cabreros Andantes – Cabrero being goat herd, and Caballero being gentlemen,

Adam Huggins 07:21

These self-proclaimed "goat herders errant" would meet regularly to schedule milking slots, and the chance encounter I've alluded to occurred on the evening of May 4, 1981. At one of those meetings, Tom Orum was there and he remembers the night well,

Tom Orum 07:37

We were having a goat group meeting – Los Cabreros Andantes. We were passing the signup sheet around, and this guy who was connected with our Baja project,

Adam Huggins 07:50

a Quaker named James Dudley.

Tom Orum 07:52

He was driving a van up from Sonora, and picked up a Salvadoran guy and came into goat group meeting and described what had happened.

Adam Huggins 08:02

Dudley had been driving from the border town of Nogales north to Tucson, and had picked up a hitchhiker from the small Central American country of El Salvador. Almost immediately, they reached a border checkpoint, and border patrol agents seized the Salvadoran, who had no papers

Border Patrol Agent 08:20

[unitelligible] a high area for us, that's why we're pulling almost everybody over.

Adam Huggins 08:24

And that was that. Dudley kept driving, stopped by the meeting, and told the story to the group. At the time, it seemed like it could have been an isolated incident. But Jim took it seriously.

Tom Orum 08:35

Well, it was like serious, but it didn't get real serious until Jim woke up the next morning and decided to go down and find the guy down in Nogales.

Adam Huggins 08:48

Jim was determined to speak with the Salvadoran, who was being held in custody by the I N S, or the Immigration and Naturalization Service. This was before it was subsumed within the Department of Homeland Security, post 9/11. To figure out where the man was, Jim started making cold calls. And he quickly realized that nobody in the INS or Border Patrol was going to give him any information. He was able to reach a local aid organization, and he was given a form called a G 28 that the Salvadoran could fill out in order to seek legal assistance. But first, he'd actually have to find the man.

Adam Huggins 09:27

Then, an idea came to him. By coincidence, Jim shared both first and last names with a former mayor of the city of Tucson. And so he called the IRS back and with his best, most commanding voice, he declared himself to be "Jim Corbett", and demanded information on the location of the Salvadoran. And he got it. They'd taken the man to the Santa Cruz County Jail in Nogales on the border to await deportation. Jim went down there that very afternoon. When he arrived at the jail and requested to see the Salvadoran, they set him up with another prisoner who wasn't the man in question. And once he realized this, they sat him in the waiting room, and they made him wait. Finally, when Jim became frustrated and demanded at last to see the man he'd come to see, the guard said that he was gone. While they'd kept him waiting, they'd taken the Salvadoran and shipped him off to El Centro prison in California.

10:34

And that just really hooked Jim. If they hadn't tricked him and just let him talk to the guy, who knows? But being tricked was – really set the tone for oh my gosh, this is not right.

Ann Russell 10:48

That's how it started with him was he met a guy who was taken away, and he had to find out what happened to him. So it was like one person, he met a person and then had to look for him. And then that's the thing about Jim, everything has a logical next step. And you follow it even though it may not be comfortable, and it may take you places that people tell you you can't go.

Adam Huggins 11:17

At this point, I think it's important to note that in the 1970s, the border just wasn't as militarized as it is today. Movement was much more fluid between Mexico and the United States, and a certain amount of permeability was seen as socially and economically advantageous for border communities. But in 1980, 2 things happened that set the stage for Jim's chance encounter. The first was the outbreak of civil war across Central America. In 1979, the Sandinistas, a revolutionary leftist Socialist Party, overthrew the government of Nicaragua.

News Announcer 11:54

Despite everything the government forces have thrown at them, their morale is high. And when the guns stopped firing for a moment, their chant is a victory.

Sandinistas 12:03

[Chanting]

Adam Huggins 12:08

military leaders in El Salvador, fearing similar movements in their own country, instigated a coup d'etat a couple of months later,

News Announcer 2 12:16

This kind of butchery, which is generally the activity of those on the right wing in this country, is the sort of thing which can be found on any roadside throughout El Salvador at this time.

Adam Huggins 12:27

Meanwhile, a civil war that had been ongoing since the 1960s in Guatemala was flaring up. And the military government in Honduras was waging its own dirty war against leftist groups. The Reagan administration in the United States openly supported these right wing military governments – viewing them as friendly to US foreign policy interests, and as a bulwark against so-called communism in the region.

News Announcer 2 12:53

Below in the yard of the police station, heavily armed police returned from making their rounds. There are countless instances of deaths and disappearances, in which they have been found to have played a role. Yet, they are armed with NATO weaponry, which the United States is continuing to supply.

Adam Huggins 13:11

We now know that the CIA was covertly funding and arming death squads, and other right wing paramilitary groups throughout Central America, the most infamous of which were Battalion 316 in Honduras and the Contras in Nicaragua, the namesake of the eventual Iran-Contra scandal. This history is complex and multifaceted. But the end result was the violent displacement of millions of Central Americans in the 1980s. Due to civil war, US backed death squads, and government campaigns of terror aimed at political dissidents and indigenous peoples. And so, in 1981, refugees from Central America started arriving in the US-Mexico Borderlands: seeking asylum and foreshadowing the 10s and 100s of thousands to come.

Adam Huggins 14:04

The second thing that happened was the passage in 1980 of the Refugee Act in the United States. This law, shepherded by outgoing President Jimmy Carter, brought US immigration law into alignment with international human rights standards: more than doubling the number of refugees that the United States would admit each year, and establishing a well-founded fear of persecution as the standard by which to judge asylum applicants. This legislation expanded eligibility for many refugees and asylum seekers, but unfortunately, was not immune from the politics of the day.

Adam Huggins 14:39

Under the newly-elected Reagan Administration, refugees from countries that the US considered adversaries, such as Cuba and Iran, were accepted and naturalized in large numbers thanks to the Refugee Act. On the other hand, the Reagan Administration's overt support for the right wing governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, meant that It refused to acknowledge the atrocities committed by those governments against their own citizens.

Adam Huggins 15:06

By extension, throughout the 1980s, nearly all asylum seekers from Central America were considered by the Reagan era ins to be, quote unquote, economic migrants, regardless of their well-founded fear of persecution. In 1981, a refugee from Cuba would find the door wide open under Reagan's INS. But the Salvadoran that Jim was trying to locate, didn't have a chance in hell.

Adam Huggins 15:39

Jim would drive all the way to El Centro present in California to try to help the Salvadoran refugee to no avail. That's a story in and of itself. But while Jim is out there, I'm going to take a moment to give John Fife, the pastor I spoke to in the last episode, a proper introduction. Because if Jim was the spark that ignited the Sanctuary Movement, John would provide the hearth that sustained it.

John Fife 16:10

My name is John Fife. I grew up in the mountains of southwestern Pennsylvania, near West Virginia, and small town, rural farm life was my heritage.

Adam Huggins 16:26

John wanted to be a pastor. So he enrolled in seminary, and when he started looking for internships, he got a call from a man from Tucson, Arizona.

John Fife 16:36

And he says "we have an internship out here and got your name and wondered if you'd be interested in". I said "well, tell me a little bit about that." And he did the job description and a little bit about the desert in the border. And, and he said "Do you have any questions?" And I said, "Yeah, I got to what's an Indian? And what's a reservation?" And he went, "Oh," and I said "well you need to know, I'm from Western Pennsylvania. I don't know anything about the Southwest. I've never been in the southwest. I don't know anything about Native Americans." And there's a kind of long silence. And he says "well, church has done a lot of damage to Native Americans over the years, you probably can't do too much more in three months once you come out." And so I said "I'd love to, if that's if we understand each other."

Adam Huggins 17:29

John left the mountains of southwestern Pennsylvania for the Borderlands of southwestern Arizona, and never looked back.

John Fife 17:37

The Sonoran Desert was a wonder and the border and the multicultural context of Native Americans and Latinos and African Americans and gringos all in here in the border region. All of the advantages of that kind of multicultural context and multi ecological context from the tops of the mountains to the Sonoran Desert. And so I just couldn't believe there was a place like this and my wife and I moved out here after I finished graduate school and stayed since 1969. Yeah, I love it.

Adam Huggins 18:21

Before long, john would become the pastor for Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson.

John Fife 18:27

This church is located in the oldest and poorest barrio in Tucson, and it had a history of beginning as a Native American congregation in the Native American village outside the south of the city of Tucson because Native Americans weren't allowed to live in the city of Tucson, and then is the city grew around here and it became a Mexican American and Native American barrio, the congregation became multicultural and bilingual or trilingual.

Adam Huggins 19:07

By the time that John arrived, a once thriving congregation was now struggling to sustain itself and was at threat of being closed by the Presbyteriat. Under John's leadership, though, the church grew strong again, supported by this multi ethnic, multi lingual community. And then came 1988.

Archbishop Oscar Romero 19:25

[Archival speech in Spanish]

Adam Huggins 19:31

In March of 1980, the Archbishop Oscar Romero was assassinated in El Salvador by a US-backed death squad for speaking out against military violence.

Archbishop Oscar Romero 19:41

[Spanish continues, followed by applause]

Adam Huggins 19:46

His death was the most high profile in a series of attacks against Christian priests and nuns across Central America. And the event galvanized John Fife and his congregation at Southside

John Fife 19:56

And so we started weekly prayer vigils in front of the Federal Building, and guess who showed up – Jim Corbett – at some point at those weekly prayer vigils saying "I just had an experience with a refugee young man from El Salvador that I tried to help and was unable to because the Border Patrol moved him to a detention center in California, and I wasn't able to prevent his deportation like I'd hoped to." So Jim was essential right from that point on. He actually talked to the head of the Immigration Service here in Tucson, and reached an agreement with him that if we would take in voluntarily Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees who wanted to apply for political asylum, he would not detain them, he released them to our custody.

Adam Huggins 20:58

At first, Jim worked with a small women led organization called Manzo Area Council in Tucson, to try to render aid to refugees through legal channels. But because of his experiences with how law enforcement treated migrants, Jim was cautious.

Jim Corbett 21:14

So I was apprehensive because I didn't trust him. I, you know, I'd been to El Centro and I knew how they operated. But it seemed to us the best option for most of the refugees to file for asylum, as long as they were reasonably sure of getting two or three years, in terms of appeals.

Miriam Davidson 21:36

It was more of the time – buying time than the idea that they would get it?

Jim Corbett 21:41

Yeah we knew they wouldn't get and that had already been established that the Reagan administration was not going to give Salvadorans asylum. But the thing was that this would allow people to be out in the open, move around at will and not risk being simply grabbed and deported anymore. At least not risk it in the same way others would.

Adam Huggins 22:04

Jim negotiated an arrangement with an officer at the local Immigration Service, he would bring in refugees and the proper paperwork. And they would begin processing the asylum claim and let the refugees go on conditional status.

Jim Corbett 22:17

Sit down and wait your turn. And then eventually they call you up and you present the person and the I 589. And they look through it and give you a little receipt.

Adam Huggins 22:28

And then one day, when Jim brought in several men seeking refugee status, this arrangement seemed to fall apart. After making Jim wait longer than usual, that same immigration officer came out and said

Jim Corbett 22:40

"We're gonna go downstairs to investigations and –

Miriam Davidson 22:44

Did he tell you right there that he was going to arrest them or...

Jim Corbett 22:47

He said we're gonna make an inquiry. At any rate, it was clear that things were going sour.

Adam Huggins 22:53

They took the men that Jim had brought with him into custody. All parties agree upon that point. The reasons for this are disputed, though, according to the INS, it was because the men had criminal records. However, Jim recalls the decision being wholly unjustified.

Jim Corbett 23:08

At no point did he give that as a reason for having done this.

Adam Huggins 23:13

In Jim's mind, the US government had already declared war on Central American refugees. But this, this was the moment when it also cut off any legal pathway for US citizens to try to help them

Jim Corbett 23:26

And made it fairly clear that this was a position that we could expect in the future as well for the people we brought in.

John Fife 23:36

And Jim came to me at that point, and said, "John, I don't think we have any choice under the circumstances except to start smuggling refugees safely across the border. So they're not caught by Border Patrol or immigration authorities." And I basically said, "really, how do you figure that Jim?" And his rationale was compelling. He said, "look at two moments in history." He said, "The first is the abolition movement, when some people of faith helped runaway slaves cross state lines safely, without being captured, and then formed an underground railroad to move them to safer and safer places, so they wouldn't be captured under The Fugitive Slave Act and return to slavery." And he said, "as we read history, those folks got it right. They were faithful."

John Fife 24:43

And then he pointed to almost the complete failure of the church in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. To protect Jewish refugees who were fleeing the Holocaust, crossing national borders, without documents – being captured as illegal aliens, and returned to the tender mercies of the Holocaust. And he said to me, "that's one of the most tragic failures of faith of the church in history." And I said, "Well, yeah, that's how I read history." And his response. He looked me right in the eye and said, "I don't think we can allow that to happen on our border in our time". And after some sleepless nights, I went back to him and said, "Yeah, you're right. I, I cannot claim to be a person of faith, or even a pastor of a faith community. If I tell you no, I, of course, you're right. We have to do this."

Adam Huggins 25:59

Beginning in the summer of 1981, Jim Corbett undertook the first of what would become hundreds of risky trips to the border to help Central American refugees safely across and up to Tucson. He didn't do it alone. He had the help of Los Cabreros Andantes. As he writes in Goatwalking.

Goatwalking 26:18

Few groups could have been better prepared, bonded together and predisposed than the Cabreros Andantes to help the refugees get through. Errantry shifted from goat herding to refugee aid.

Adam Huggins 26:34

I really want to stop and emphasize this point for a moment. In my own reading of history, people who cultivate intimate relationships with the more-than-human world often become leaders, and resources in times of disaster, of deprivation, and of demagoguery. In this respect, I would argue that you could draw a straight line from St. Francis of Assisi to Henry David Thoreau, and right on to Jim Corbett. Few people would have made the decision that Jim and John made, and fewer still would have actually been able to pull it off. Jim's years of roaming in the desert with his goats turned out to be a singular contribution.

John Fife 27:15

Oh, it meant everything. I mean, what does some gringo from Western Pennsylvania know about smuggling refugees across the border? It was all Jim's conception and Jim's practice. And then Jim's training of other volunteers in that practice. That was the foundation of everything we did.

Adam Huggins 27:40

By this time, Jim and his inner circle had already formed relationships with a Catholic priest, Father Quinones at the Sanctuary of Guadalupe church on the other side of the border in Nogales, Father Quinones would do weekly visits to the local Mexican prison, where migrants were held awaiting deportation. And Jim would join him, new groups of migrants would arrive and depart every week. And the conditions in the jail were not good.

Jim Corbett 28:03

Yeah, it was just a concrete holding tank with nothing to sleep on. And normally, when we started working on it at a later point, no, no blankets or anything they just slept on the concrete floor. It was open air, so it got very, very cold in the winter.

Adam Huggins 28:22

Once there, he do refugee support work, helping supply blankets and mattresses and sanitary products, as well as assisting the refugees and connecting with family members. He'd also use these visits as an opportunity to learn about how they traveled from their homes to the border, and how they crossed – and how they got caught. This research ended up being really crucial, because in the summer of 1981, the floodgates opened, Central American refugees began arriving in the Borderlands in unprecedented numbers.

John Fife 28:52

And so with a group of about, I don't know, 20 or So folks, in cooperation with a Catholic priest in Nogales, Sonora, who had been running a shelter for Central American refugees to protect them there in Mexico. He would refer families to us, we would cross them bring them to Tucson,

Adam Huggins 29:12

Jim and other volunteers were making daily trips to Nogales to help them across.

Jim Corbett 29:16

It was just almost every day people were just coming through so fast.

Adam Huggins 29:21

They'd do this all sorts of ways. For example, Jim learned of a hole in the border fence on the east side of Nogales – and when it would be watched.

Jim Corbett 29:29

And there were certain times when the hole was really just left unattended. So if you knew the times when they weren't going to bother, you'd just always make it and then in '81, you know just day after day after day people were going through...

Adam Huggins 29:44

And Jim would find those people and transport them safely past the Border Patrol to Tucson. Throughout summer in fall of 1981, Pat Corbett remembers him being in constant motion.

Pat Corbett 29:55

Oh gosh there for a while. He'd be just, you know, three or four trips a day to Mexico. Really, I don't know how he did it,

Adam Huggins 30:04

We'll probably never know entirely. But in those early days, he did it mostly just by picking folks up and driving them north in his truck.

Pat Corbett 30:12

At that time the Border Patrol wasn't so you know, on the lookout for that kind of thing. So it wasn't as hard as later became.

Adam Huggins 30:20

As sanctuary activities became more public and the situation worsened in Central America, the border tightened up. Civilized ports of entry were fortified, forcing migrants to attempt to cross the border in extremely dangerous, sparsely inhabited stretches of desert, where untold numbers would die over the coming decades.

Adam Huggins 30:45

This policy of prevention through deterrence, and its deadly results are well documented today. But in the early 1980s, large groups of migrants dying in shocking numbers in the desert was still a novel phenomenon. In response to this fortification, Jim used his incredible knowledge of the Sonoran Desert ecology and geography to help groups of migrants cross by foot. Those lucky enough to cross with Jim, were in good hands.

John Fife 31:13

I've spent days and up to a week with him in the desert. It wasn't goatwalking, it was smuggling refugees. So I learned a lot from him in those brief periods, about desert survival and about what he was thinking, and about what he was teaching.

Adam Huggins 31:33

Jim's knowledge would carry the group's safely across this harsh terrain. Of course, it wasn't easy.

Pat Corbett 31:40

I think the refugees, you know they were pretty accustomed to a tough life. And even so I think they found Jim's idea of how to pack across the desert in the mountains pretty tough.

Adam Huggins 31:53

Eventually, the iconic quality of these desert crossings would make front page news. Journalists from major publications like the Chicago Tribune, would follow Jim into the desert to get the full story.

Ann Russell 32:05

But that didn't stop them from taking refugees from the border up into the Chiricahua mountains wearing his sandals. On one time there was a TV crew from LA out with him and they couldn't hack it. And there's Jim with his sandals and his arthritic toes, just walking through the mountains.

Adam Huggins 32:39

But that was just getting folks safely across the border. Then there was the question of what to do with them. At first, Jim would bring the refugees to his and Pat's apartment in Tucson, which quickly filled up. Here's a recording of a talk that Pat gave to a group of Quakers reflecting back on that time,

Pat Corbett 32:58

A reporter in Washington DC once asked me what my role was in the Sanctuary Movement, which kind of befuddled me and it still does. But I thought a while and I said, Well, I guess I was the plumber. The reporter looked quite stunned by this. And after a while, I realized that she thought I meant a watergate type of plumber, when I was speaking quite literally of the problems involved in having sometimes 20 or more people using a septic system meant for two.

Adam Huggins 33:31

While Pat was dealing with the immediate problems presented by hosting too many people under one roof, Jim and the other Cabreros Andantes reached out through their networks to find temporary accommodation for these refugees. One of the people who answered that call was Gary Paul Nabhan

Gary Paul Nabhan 33:48

My first year in Tucson – after living on ranches and national parks in southern Arizona – I ended up in a community garden group with Jim and his wife and many of their dear friends – at least half of them literally friends, Quakers. And we not only shared garden space, but we helped with goat milking. Because Jim was still doing his goatwalks.

Gary Paul Nabhan 34:17

But he was really the first philosopher I knew who had such a deep grounding in western and eastern traditions, that he took principles from perennial traditions and adapted them to social justice here in the Borderlands. And he did it in a very non egotistical way. He didn't announce things he'd say something like, "Gary, I have some friends that I'd like you to meet that are just passing through town and they share a lot of your same interests. Could you meet us at the Denny's a few blocks away from your house?" And I'd get over there and there'd be a Guatemalan family that needed help filling out the refugee papers in one state for a month with us and finally got reunited with their extended family in California.

Adam Huggins 35:09

Like many people who befriended Jim and participated in sanctuary, the experience was life changing for Gary.

Gary Paul Nabhan 35:15

And I realized that well, at that age of my 20s, I thought it was just a good thing to do. I had no sense of how much suffering they had gone through, and how even coming to the United States ended up not to be a solace or a sanctuary immediately, but a struggle to feel legal, and to feel like they had their dignity and overcome the post traumatic stress of not just what took them from their homeland, but all the trials and tribulations they faced in Mexico. And Jim somehow knew that from his own life and sort of guided those of us who are facing it, for the first time – that it's not a cup of tea, hosting refugees. They're going through deeply troubling issues that you need to accompany them with. And I thought it was giving them a room, and I realized afterwards that was giving them my heart and my attention and my listening.

Adam Huggins 36:20

We'll return to Gary later in this series. But for now, I'll just say that Gary's experience is typical of those who became drawn to sanctuary work by Jim helping people felt good, but the traumas that those people carried were with them all the time.

Pat Corbett 36:35

Oh, the stories you would hear from them were appalling.

Adam Huggins 36:38

These were people who in many cases had directly experienced unimaginable violence against their person or their close family members, and who felt that remaining in their homes was more dangerous than the perilous journey northward. Traversing Mexico was and is extremely dangerous for Central American migrants. The US had put increasing pressure on Mexican authorities to prevent Central Americans from even reaching the US border. And this criminalization of migration, subjected migrants to organized crime, police corruption, and worse things. It was especially dangerous for female refugees.

Jim Corbett 37:16

So a lot of it really had to do with the whole problem connected with women in that it if they are young and saleable, they're indefinitely exploitable, and as refugees are completely vulnerable,

Adam Huggins 37:32

For these female refugees, they risked not only being killed, but also being exploited and trafficked for sex. If they were deported back to Central America, or captured by police or criminals in Mexico, they were in an incredibly difficult position. So while there were folks like Gary, who took refugees in, in those early days, most of the Central Americans still ended up living with Jim and Pat in their tiny apartment,

Jim Corbett 37:58

It was just a really a very difficult thing to cope with all the folks and at the same time. Someone was arriving new on virtually every day. And most of my energy was going into getting them through without there being caught, which meant I brought them into Tucson and then hope someone would do something. And frequently Pat and I were doing it at the apartment that is in terms of the people crowded in there. And if I was going to be responsible, in some sense for trying to cope, it was easier to cope with 20 people crammed into the apartment where I lived and to try to run around town, figuring out what to do with folks somewhere else. So it simply reached a point of extreme overload.

Adam Huggins 38:43

With their apartment full, and at their wit's end, it was clear for Pat and Jim that something needed to change. In hindsight, what happened next was a stroke of sheer brilliance. Jim told it like this.

Jim Corbett 38:56

Oh, yeah, there's been a period of several weeks where Pat had been talking about the need to find some church or someone who could take care of the refugees. And that was especially urgent because I was planning to go down to Chiapas and Guatemala. And it became clear that it just wouldn't be good to leave Pat alone, trying to tend to the apartment down full of refugees.

Adam Huggins 39:24

Pat tells it like this.

Pat Corbett 39:25

At one point, I finally was saying to Jim, that you should go talk to some of these church people who were also concerned about the refugees. Because they have these churches with lots of room, lots more room than we had, and better plumbing. And so poor John five, Jim picked on him. And he went to his congregation and they had a congregation discussion about it and decided that they should start housing refugees, so I was able to let them have my 21 or 22 refugees. Great sigh of relief

Adam Huggins 39:58

And John – he tells it like this:

John Fife 40:01

And then both Pat and my wife got together and threatened divorce and said, "Come on, guys, we can't be trying to provide all the care that refugees present to us in terms of their needs in our homes." And so that's when Jim came to me and said, "can we bring those folks to the church?"

Adam Huggins 40:26

By all accounts, I think we can conclude that Pat was responsible for moving sanctuary from a tiny apartment to the churches of America, setting the stage for a national modern day Underground Railroad.

John Fife 40:41

That's probably an accurate rendering of history in my judgment, yeah.

Adam Huggins 40:48

From this point on, sanctuary would be spelled with a capital S.

Adam Huggins 41:01

On March 24 1982, Southside Church publicly declared itself to be a Sanctuary for the oppressed of Central America. By 1985, over 500 congregations joined creating a national movement, with 1000s of volunteers working to shelter, transport, and house refugees from war torn Central America. Jim, the solitary Quaker, had finally found a home in the church, and his principled stand had created a movement that defied the most powerful government on the face of the earth.

Adam Huggins 41:40

You might have a few questions at this point. For example, how did Sanctuary volunteers ensure that the migrants that they were helping were actually refugees? The answer is the church. When he wasn't helping folks cross the borderm Jim traveled extensively throughout southern Mexico and Guatemala during this period, tapping into a network of churches that extended from Latin America, north to the United States. The pastors of these congregations took incredible risks to help migrants on their way north. And in the process, they would vet the migrants to make sure that they weren't unknowingly sheltering people who had no legitimate claim to asylum. By the time these folks actually reached the US border, the Sanctuary network would be able to vouch for them as refugees, regardless of the US government's intransigence on the issue.

Adam Huggins 42:28

Later in this series, we'll critique this notion of deserving refugees versus undeserving economic migrants. But for Jim and the other sanctuary volunteers, it was important that they took extreme care to make sure that sanctuary volunteers weren't unknowingly doing the work of coyotes, or other smuggling operations.

Adam Huggins 42:49

Another question, how did these churches organize themselves? The answer is through lots of meetings and letters. The horizontal structure of the Sanctuary Movement meant that no one was in charge. And although John and Jim tended to act as national spokespeople, each congregation functioned voluntarily and autonomously. This sometimes led to issues such as certain congregations wanting to politicize the refugees they helped, by asking them to speak out against the right wing governments of Latin America. Jim was strongly against this politicization of sanctuary.

Jim Corbett 43:22

It was very firm with everyone here, that that particular approach was one that was morally wrong, that it really is wrong to deny people aid because they don't fit your political purposes. It's wrong to pressure people into fitting your political purposes, who are in desperate situations.

Adam Huggins 43:50

In Tucson, at least, Sanctuary would be offered to asylum seekers, regardless of their political orientation. At the time, this elevation of human life over political expediency contrasted sharply with both US government, and more ideological leftist groups and congregations.

Adam Huggins 44:09

But the question that I'd like to examine for the rest of this episode, is how did the Sanctuary Movement choose to justify its actions to the citizens and the government of the United States?

John Fife 44:19

Well, when we finally in March of 1982, declared Southside Church's as Sanctuary for Central American refugees and received a mother father and two kids – two little kids – in publicly into the sanctuary of the church, I thought and Jim thought, at that point, that we were doing civil disobedience in the tradition of King and Gandhi and Thoreau, and going back to Moses's sister who hit him along the Nile to keep Pharaoh from killing all male children back there

Adam Huggins 44:58

Civil disobedience, as many of us are taught in grade school, is a term popularized by 19th century American author Henry David Thoreau. You know, the guy who lived in a cabin on Walden Pond and went to prison for refusing to pay his taxes.

John Fife 45:13

And so I talked about King and quoted Gandhi and went on and on when we did the public declaration of Sanctuary here. And about a month after we had done that, I get a call in my office, and this guy says, "I'm a human rights attorney from New York. And you've got to stop talking about civil disobedience. You're not doing civil disobedience." And I laughed, and I said, "What do you mean, the government says they're going to indict us any day now. They keep saying that, and I'm just sitting around waiting for the documents." And he said to me, "Listen, dummy." That's a direct quote, "you're not doing civil disobedience. It's the government that's doing civil disobedience. It's the government that's violating United States refugee law. So every time you talk about civil disobedience, people get it all mixed up. So stop it." And I said, "Oh, I think I understand. But what do we call what we're doing now?" And he said, "I don't know make it up." And so I went to Jim told him about the phone call. And he kind of smiled and came back about three or four days later, with this whole paper that he called on civil initiative.

Adam Huggins 46:37

In his essays on the topic, Jim converses with Thoreau, Gandhi, and Hobbs to articulate a new paradigm for radical justice. He called it civil initiative.

Goatwalking 46:50

Civil initiative maintains and extends the rule of law. Unlike civil disobedience, which breaks it, and civil obedience, which lets the government break it.

Adam Huggins 47:03

Civil initiative reframed the discussion, casting the government as the one that was violating its own laws, and higher laws as well.

Jim Corbett 47:11

Conventional civil disobedience would simply concede to the government the destruction of the refugee laws – that what was at stake was international human rights and humanitarian law and the domestic refugee law. And that it was very important not to take a traditional civil disobedience approach. If we were going to save the laws, because if when the government violates the law that way, and is attacking it, you simply concede their legitimacy and say that you're breaking the law, then that just does it in. You're not going to save the law, any of the law at that point.

Adam Huggins 47:51

This framing was crucial in convincing so many people who would not otherwise engage in quote, unquote, illegal behavior, to take up Jim's proposition of collectively enacting US immigration law at the grassroots level, even as the US government itself under the Reagan administration violated it.

John Fife 48:09

I mean, it's one thing to go to Presbyterian churches or Catholic churches or Jewish synagogues and say, "we'd like you to join us in doing civil disobedience with all of the negative and risk aspects, that that would have entailed," it's quite another thing to go to them and say "it's the government that's violating human rights and United States law. Join us in an active public resistance to government crimes." That puts a very different incentive and prospective for risk taking under those conditions. It meant we were able to build a movement quickly.

Adam Huggins 48:51

This movement, grounded in international human rights law, US law, as it was written, and the divine laws of the church, joined a long tradition of people, especially Indigenous people and people of color, who had risked everything to defy a US government, which, throughout time, has steadily refused to live up to its own laws, principles, and founding documents.

John Fife 49:13

Oh, sure, if you look back, you can make a clear case that Dr. King was not doing civil disobedience. He was doing civil initiative, as we understood it in our movement. You can go on and on and on throughout history and say, "no, no, that's not civil disobedience."

Adam Huggins 49:32

Today, when I think of mutual aid movements, and so many people coming together to resist the wholesale destruction of human and biological communities. I think of the power of this reconceptualization of civil disobedience to civil initiative. It acknowledges a fundamental kind of work that we can only do when we act as a community. Jim would later write:

Goatwalking 49:56

Individuals can resist injustice, but only community can do justice.

Adam Huggins 50:07

Of course, the US government acknowledges no higher authority than its own, in practice. And it was only a matter of time before Jim, John, and a number of other sanctuary volunteers were brought to trial. The Sanctuary Movement had been infiltrated, and covert tape recordings were made, followed by charges. The judge was prejudiced and wouldn't allow Jim and his co-defendants to present a defense at all – ruling that no discussion of sanctuary or refugees would be admitted. The story of the trial is fascinating, and has been thoroughly documented in other media, including the 99% Invisible series. The outcome: several folks were convicted, including John Fife, but Jim and others were found innocent, and the charges were later overturned, or sentences reduced. Ironically, Jim Corbett, the man that the government had wanted most to convict, hadn't been in Tucson when the government informit infiltrated the sanctuary network.

John Fife 51:05

He was spending all of his time border south to Central America, putting that part of the Underground Railroad together so we could get people safely out of Central American and to the border. And so they had no evidence against him. So that's why he was found innocent

Adam Huggins 51:24

In the end, what the trial served to do was to strengthen the Sanctuary Movement, giving it a national stage and the righteous narrative of the church standing up to a tyrannical government. Sanctuary in this incarnation would continue into the late 1980s, until the number of refugees seeking asylum began to decrease. For Jim, the end of the trial also signaled to him that he could finally start to step back from Sanctuary work.

Jim Corbett 51:51

In some measure, I can, I think, now turn back to the things that I choose to do. My agenda has been set by the refugee situation, I wouldn't have simply chosen this out of the various social concerns. If I have been choosing, and environmental concerns and rediscovery of the Sabbath, are some of the things that I am very interested in pursuing now, I think I have the chance to attend to, I might even do a new, revised, updated version of Goatwalking manuscripts.

Adam Huggins 52:29

This would be the time that Jim would finally finish his first book, Goatwalking. But he also had a new project in mind. One that spoke more to Aldo Leopold, than to Henry David Thoreau.

Jim Corbett 52:41

And the whole development of the land ethic in which there is protective, symbiotic community at work. So that, I think my attitudes with regard to the refugees, the reasons I took the course of action I did were very much formed by this other broader attitude towards the fact that human beings have an enormous responsibility to bring into full, reflective consciousness that community that does exist among all living things. That life is in fact among us rather than in us. And that definitely has a bearing on my understanding of what Sanctuary is. And Sanctuary in its broadest sense extends far beyond Central America and specific human refugees, to the need for a harmonious community among all living things,

Adam Huggins 53:39

Extending Sanctuary to all life. That's next time, in part three of Goatwalkar.

Adam Huggins 53:52

Goatwalker is produced by myself, Adam Huggins and Mendel Skulski for Future Ecologies. Ilana Fonoriov is the Associate Producer for the series. For photos, citations and more information about the people and events described in this episode, including some truly incredible photos of Jim from the Sanctuary years. Please visit futureecologies.net.

Adam Huggins 54:14

In this episode, you heard Ann Russel, Tom Orum, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Gary Paul Nabhan, Jim Corbett, and Miriam Davidson. Narration was by Philip Buller

Adam Huggins 54:27

Music was by People with Bodies, Meteoric, Hidden Sky, and Sunfish Moon Light. The Goatwalker theme is by Ryder Thomas White, and Sunfish Moon Light. Special thanks to Theresa Madison, Susan Tollefson, John Fife, Pat Corbett, Nancy Ferguson, Tom Orum, Gary Paul Nabhan, Gita Bodner, Amanda Howard and the University of Arizona, Sadie Couture, Phil Buller and Danny Elmes

Adam Huggins 54:55

Future ecologies is an independent production supported by our patrons. To join them, go to patreon.com/futureecologies.

Adam Huggins 55:03

This series was recorded on the territory of the Tohono O’odham, and produced on the unceded, shared, and asserted territory of the Penelakut, Hwlitsum, Lelum Sar Augh Ta Naogh, and other Hul’qumi’num speaking peoples.