Kelp Forest by Alex Mustard

Summary

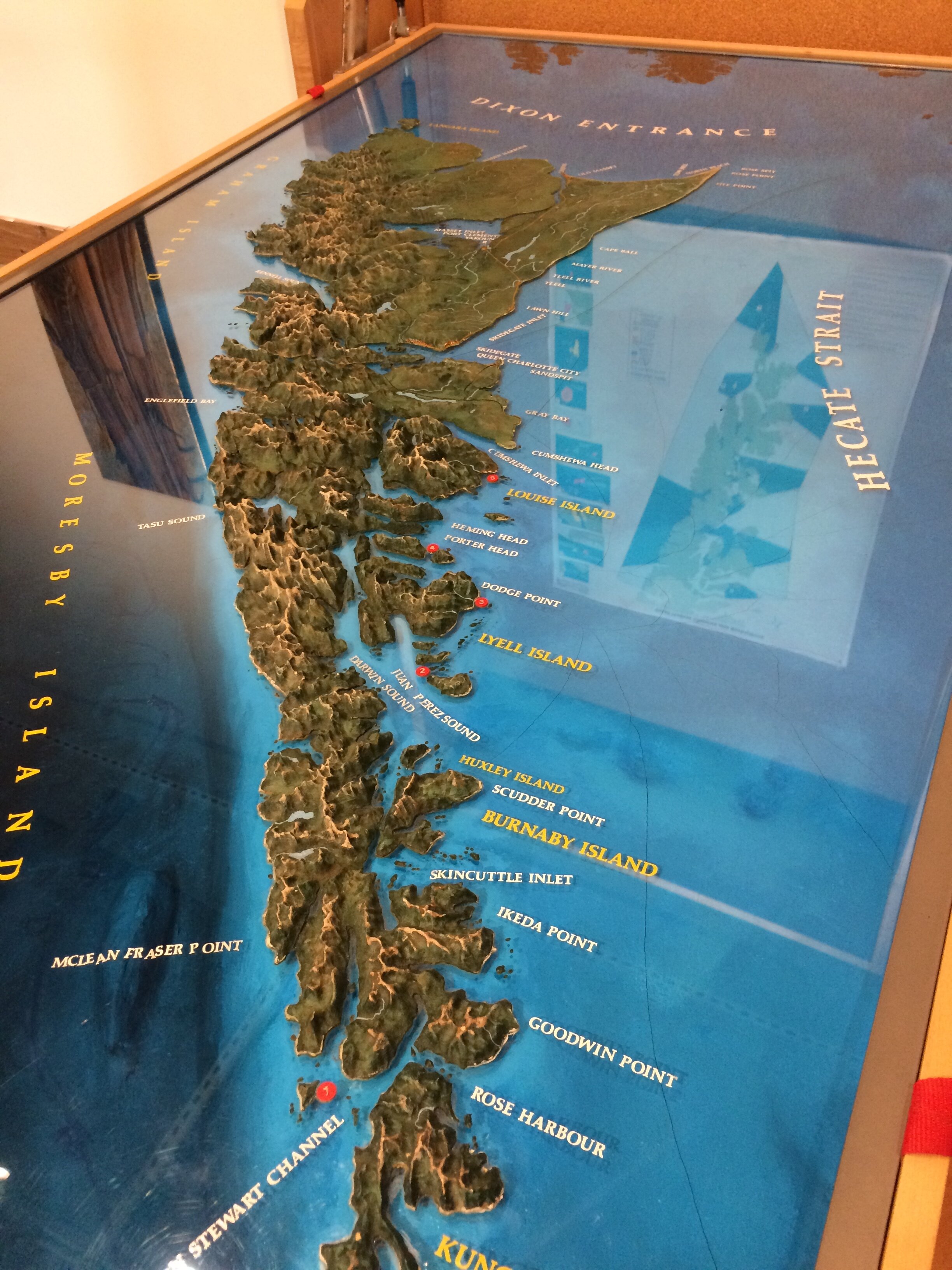

To find out what the future might hold for Kelp, Sea Otters, Urchin, and Abalone, we're taking you to Haida Gwaii – an archipelago famous for both its deep culture and unique ecology. In Gwaii Haanas, the Islands of Beauty, a surprising experiment is taking shape, and we're going to dive right in.

We go from mountain top to sea floor, and we finally get to meet the fastest snail in the west.

This is part three of our three-part series on kelp worlds. Start with Part One: Trophic Cascadia, and then Part Two: Ocean People

Abalone, Urchin, and Kelp by Ryan Miller, courtesy of Parks Canada

Diver Smashing an Urchin by Ryan Miller, courtesy of Parks Canada

Photos from our travels to Haida Gwaii

(all photos by Mendel or Adam)

Show Notes

Since we visited Gwaii Haanas in the Summer of 2019, the study has progressed! Here is an April 2020 update from Lynn Lee:

[Before and after restoration work at the experimental kelp forest site]:

• Summer kelp depth went from 0.5 m chart datum to about 8 m depth chart datum

• Summer kelp density went from almost 0.1 plants (stipes) to more than 1 plants per metre squared, a 10-fold increase!

• Red urchin densities were reduced by over 90% to successfully mimic sea otter predation on urchins

Most of the kelp that returned to the site when you saw it was annual kelp, which means that it does back every fall/winter. We will need to revisit the site again this summer to see if the kelp continues to come back and the urchins continue to stay away.

This episode features Stu Crawford, Captain Gold, Lynn Lee, Dan Okamoto, Nate Spindel, Kii’iljuus Barbara Wilson, Anne Salomon, Charles Menzies, Nate Spindel, Ollie Popley, Crystal Young, Shayanna Sawyer, Hannah Freegan, Stu Crawford, Jenn Chow, and Yarrow.

Music in this episode was produced by Aner Andros, Hildegard’s Ghost, the Hot Sugar Band, Ben Hamilton, and Sunfish Moon Light.

This episode was produced by Adam Huggins and Mendel Skulski

Special thanks to Miranda Post and Parks Canada, Chloe Clarkson, Winnie Tsai, Ollie, Stu, Jen, and Yarrow, Leigh-ann Fenwick, Sheena Briggs, and Kieran Wake, without all of whom this adventure would never have been possible.

This podcast includes audio recorded by CaganCelik, sandyrb, jpnien, InspectorJ (Helicopter Flyby, Distant A.wav), and vataaa, protected by Creative Commons attribution licenses, and accessed through the Freesound Project.

A lot of research goes into each episode of Future Ecologies, including academic literature and great journalism from a variety of media outlets, and we like to cite our sources:

Lee, L. C., Watson, J. C., Trebilco, R., & Salomon, A. K. (2016). Indirect effects and prey behavior mediate interactions between an endangered prey and recovering predator. Ecosphere, 7 (12).

McLeish, T. (2018). Return of the sea otter the story of the animal that evaded extinction on the Pacific Coast. Seattle: Sasquatch Books.

You can subscribe to and download Future Ecologies wherever you find podcasts - please share, rate, and review us. We’re also on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and iNaturalist.

If you like what we do, and you want to help keep it ad-free, please consider supporting us on Patreon. Pay-what-you-can (as little as $1/month) to get access to bonus monthly mini-episodes, stickers, patches, a community Discord chat server, and more. This season, Mendel guiding a tour of mushrooms and the Kingdom Fungi.

Future Ecologies is recorded on the unceded territories of the Musqueam (xwməθkwəy̓əm) Squamish (Skwxwú7mesh), and Tsleil- Waututh (Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh) Nations - otherwise known as Vancouver, British Columbia. This episode was also recorded on Haida territory.

Transcription

Mendel Skulski 00:00

Hey everyone, just so you know, this is the final installment of a three part series on kelp worlds. If you're just tuning in, we'd like to encourage you to listen to parts one and two first. Everything will make a lot more sense that way. And if you're trapped inside your home in response to this Corona virus, we're thinking about you right now. And we're about to transport you far, far away. Unless, of course, you live on Haida Gwaii. Anyhow, here's the third and final installment of our series on kelp worlds.

Introduction Voiceover 00:12

You are listening to season two of Future Ecologies.

Adam Huggins 00:14

Hey, this is Adam.

Mendel Skulski 00:14

And Mendel.

Adam Huggins 00:15

And if you've made it this far, to episode three of our series on kelp worlds, congratulations. You are officially a nerd like us. [Mendel laughs] And thanks for listening. [laughs] To wrap this series up, we're going to do something a little different. We're going to take you on a field trip.

[Playful music begins]

Mendel Skulski 00:22

Specifically, we're taking you to Haida Gwaii, a rugged island archipelago about 60 kilometers…

Adam Huggins 00:25

That's 40 miles.

Mendel Skulski 00:25

…off the north coast of British Columbia and southeastern Alaska. About 4,500 people call these islands home, and nearly half of these belong to the Haida Nation, including Kii'iljuus, Barbara Wilson, who you heard in our last episode.

Adam Huggins 00:38

So, an archipelago is basically a collection of islands. And Haida Gwaii consists of about 150, ranging from these tiny little outcrops where rare seabirds like to nest, to majestic, mountainous Moresby in the south and beautiful, boggy Graham in the north. It's surrounded by some of the most productive and diverse nearshore marine communities in the North Pacific. And we've come here because this is an archipelago from which sea otters were extirpated during the fur trade and where they have not yet returned. But in all likelihood, that's about to change.

Mendel Skulski 01:24

It's only a matter of time.

Adam Huggins 02:06

Along the way, we're going to eat some guuding.ngaay, visit a floating laboratory, talk to a living Haida legend, and finally meet the star of this series. And spoiler alert, it's not the sea otter.

Lynn Lee 02:20

They're actually the fastest snail in the West. [laughs] I like to tell people that little fun fact.

Mendel Skulski 02:27

Dubious distinction.

Lynn Lee 02:28

Yeah, dubious distinction, but they do move quite fast when they're running away from predators. Oh, this guy's really performing. This is awesome.

[Music fades out]

Mendel Skulski 02:35

But before you slip into your wetsuit and grab your snorkel, we've got some climbing to do. We're on a mission to find a rare plant. And we've enlisted some local guides to help us out.

Stu Crawford 02:46

We're gonna have a, kind of not so interesting slog, for a bit as we get to this clear cut.

Adam Huggins 02:52

Okay.

Stu Crawford 02:53

And then there'll be more stuff.

[Bird calls]

Adam Huggins 02:59

This is Stu.

Ollie Popley 03:02

I'm Stu Crawford. I live in Haida Gwaii. I work for the Haida Nation as a marine biologist. And I like lichens and plants and such as well.

Jenn Chow 03:15

We're on the trail of Sleeping Beauty mountain.

Mendel Skulski 03:18

And this is Jen.

Jenn Chow 03:19

My name is Jenn Chow. I'm a resident of Haida Gwaii. I work as a registered nurse. I'm a yoga teacher. I'm a mom. I'm Steve's wife. I like being outside.

Adam Huggins 03:29

And this is Yarrow.

Jenn Chow 03:32

Hi, this is Yarrow. Yeah, she's 21 months old.

Adam Huggins 03:36

Do you wanna say hi?

Jenn Chow 03:37

You say, "Hi, everyone."

Yarrow 03:39

[Adorable baby voice] Hi everyone.

Mendel Skulski 03:41

And if you're wondering why we're following a marine biologist and his family up Sleeping Beauty Mountain to look for a rare plant, well, this is just kind of what happens when you travel with Adam.

Adam Huggins 03:52

That is true. I promise though, when we get to the top you'll have a clearer view.

Mendel Skulski 03:58

Oof.

Adam Huggins 03:59

And, while we are supposed to be looking for a plant, we're spending an awful lot of time on the way up stopping to examine and sample just about everything else. I mean, we break for slime molds…

Mendel Skulski 04:15

Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa variety poroides! Have you seen this before?

Adam Huggins 04:18

...and we break for lichens...

Stu Crawford 04:20

Do you wanna see Devil's Matchstick?

Adam Huggins 04:22

What's the deal with all these names? Fairy Puke? Devil's Matchsticks?

Stu Crawford 04:25

Lichenologist are good at naming things.

Adam Huggins 04:29

...and mushrooms...

Stu Crawford 04:30

Does anybody wanna touch a goofy mushroom?

Jenn Chow 04:31

Oh, yes, Yarrow, look! A goofy mushroom...

Mendel Skulski 04:35

Oooh ooh, eyeball, eyeball! Careful, eyeball.

Adam Huggins 04:37

It's viscid as heck.

Adam Huggins 04:38

...And yes, even millipedes.

Mendel Skulski 04:41

What kind of millipedes are those?

Stu Crawford 04:42

The Haida name is çúud t'amíi. Basically it translates as Eagle Bug. It's a medicinal creature. You eat them. Would you like to try one?

Mendel Skulski 04:51

Woah. Yes.

Adam Huggins 04:54

Okay, so I've pulled the ends off and now I suck on this bit?

Stu Crawford 04:57

Yeah. You're sucking out the guts.

Mendel Skulski 04:59

Does it matter which end you start at?

Stu Crawford 05:01

I don't think so, because you just detach from both ends now.

[Slurping squelch]

Mendel Skulski 05:05

It tastes a bit like um, like a mild tofu pudding you might get with a little bit of almond flavor. Just a milliliter of it, right?

Mendel Skulski 05:14

These were all important life experiences for us, I think.

Adam Huggins 05:18

I agree. But finally, just as we're nearing the tree line, we find our plant. And what a glorious plant it is.

[music fades out]

Stu Crawford 05:28

It’s a very distinctive, very thick, solid leaves that look like a bunch of little boobs around, with little nipples on them. Nothing else looks anything like it.

Mendel Skulski 05:37

So wait, what did we just find?

Stu Crawford 05:39

This is an endemic flower of Haida Gwaii. It's its own genus Sinosenecio. There's no other species in the genus in all of North America. It's common in the alpine of Haida Gwaii, but not found anywhere else in the world.

Adam Huggins 05:55

And why would that be?

Stu Crawford 05:57

So this will have survived in a nunatak on Haida Gwaii. So, a small glacial refugia. Haida Gwaii was pretty much all glaciated but because we had our own glaciers here. They were much thinner. So, a couple of the mountain tops stuck out of the ice and something called nunatak, a little space where things could survive in the ice, but only high alpine little things are surviving, because they're very small little spots. So, there's a variety of different lichens and mosses and a couple little beetles and alpine plants that survived here. And this is one of them. And it didn't survive anywhere else.

[music fades in]

Adam Huggins 06:33

This wildflower, Sinosenecio newcombei, or Newcombe's butterweed, is one of a number of species only found on Haida Gwaii. It's endemic. Some of these species are also found in another place called the Brooks Peninsula on Vancouver Island. And these two places share a special distinction.

Mendel Skulski 06:54

During the last ice age, when much of North America and all of what we now know as Canada was covered by kilometers thick sheets of ice, there were at least a few areas here on these remote islands of the westernmost coast which remained ice-free. Where exactly and how large those areas were is still debated. But Newcombe's butterweed and other species like it present irrefutable evidence that nunataks, these little ice-free islands on mountain peaks, existed.

Adam Huggins 07:25

So it was worth the hike, right?

Mendel Skulski 07:26

Definitely. [laughs] I've learned not to doubt your instincts at this point. Also, it was worth it just to see these beautiful little patches of sunshine-yellow flowers smiling up at us, reminding us of a time when nearly everything was covered in ice up here. Well, but not quite everything.

Adam Huggins 07:44

Not quite everything.

[Sounds of breathing, Adam's voice from the mountain] It's beautiful up here.

[Back in the studio] And when we finally made it to the top, and got to look out over the archipelago, we saw how the highest peaks had this incredibly sharp, razor-like relief, unlike the hills below us, which were rolling with all the hard edges ground off by, presumably, ice sheets as they receded to the north at the end of the last ice age.

Mendel Skulski 08:14

But we also saw something else. When we looked out to the east over the Hecate Strait, the 60-some kilometer stretch of ocean that separates Haida Gwaii from the mainland, we knew that somewhere, hundreds of meters under the water, there was probably evidence of a much larger ice-free area that paleobiologists refer to as a glacial refugium.

[Music shifts slightly to a soft but exciting melody]

Stu Crawford 08:37

And it has been sort of hypothesized that Haida Gwaii had a glacial refugia. Um, the more recent work showing if there was one it was probably somewhere in the Hecate Strait, because sea level was lower. And the mainland glacier was coming off the mainland and the Haida glacier was coming off Haida Gwaii, and they kind of met. And the Hecate, there was like, maybe some large spot in there that was unglaciated.

Adam Huggins 09:04

At this point, you're probably wondering what these putative glacial refugia have to do with kelp forests. The answer is that the existence of these ice-free areas, coupled with the existence of these productive kelp-dominated marine ecosystems—these are two critical pieces of evidence to support what has become known as the Kelp Highway Hypothesis for how people first arrived in what we now call the Americas.

Mendel Skulski 09:34

Ever since Columbus first washed up on the shores of Guanahani Island in what we now call the Bahamas, and identified the people living on it as Indians, well, settlers have been confused about where the Indigenous people they were encountering had come from. But Indigenous people throughout the Americas have had no such confusion. If you ask Barbara or Charles, who we heard from last episode, where their people came from, they'll tell you.

Kii'iljuus Barbara Wilson 10:01

My people say we've always been here.

Charles Menzies 10:05

There always were people in Gitxaala territory.

Mendel Skulski 10:07

At the same time, both Charles and Barbara are able to hold the truth of this oral history alongside the questions we all share about the deep time origins and diaspora of our species.

Charles Menzies 10:19

As a metaphor for origin, it implies that for all the time that people have been culturally human, they've been in this space. And if you look at some of the early, early origin myths, they're all really about, I would argue, about being culturally human.

Kii'iljuus Barbara Wilson 10:35

I had an archaeologist, Darrell, say, "hmm, 13 years, 14,000 years, that's forever." You know, so we've always been here. We claim we came out of the water, and that our ancestors could take their marine outside coats off and hang them up and become ordinary human beings. And when they got hungry, they put them back on again. And they went out to the ocean and they ate. Okay? That's our story.

Adam Huggins 11:07

But for the better part of the past century, archaeologists and anthropologists had a different story. Based on artifacts and evidence they had gathered, they hypothesized that ancient peoples crossed a land bridge that was exposed during the last ice age from eastern Asia to northern Alaska, inhabiting a cold but unglaciated tundra known as Beringia, and surviving by tracking and hunting big game. You know, woolly mammoths and mastodons and that kind of thing.

[Noise of a big creature]

Then, about 13 or so thousand years ago, give or take, the ice sheets started to melt and an ice-free corridor opened up between the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets. Basically somewhere along the present day border between the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. As the story goes, these big game hunters passed through this corridor and rapidly peopled the entirety of the Americas, from British Columbia down to Patagonia.

Mendel Skulski 12:07

There are several major flaws that have been exposed in this hypothesis. For one, it ignores the oral traditions of the Indigenous peoples it purports to explain. But also, it doesn't explain the highly sophisticated maritime cultures that are evidenced all along the Pacific Coast, with some sites dating back to 14,000 years ago, or even earlier.

Charles Menzies 12:30

So let's just do a kind of conceptual thing. So we trudge across the Bering Land Bridge chasing large animals. We work our way down the ice-free corridor. We somehow turn around and work our way out to the coast. And then we develop an extensive maritime culture. [laughter] I don't know, I think there's some gaps there.

[Groovy music begins]

Mendel Skulski 12:53

So a new explanation, often referred to as the Kelp Highway Hypothesis, has now gained broad acceptance, the idea being that the Americas were peopled, at least in part, by these mobile oceangoing peoples that paddled from Asia all the way to Patagonia, in an arc around the perimeter of the Pacific, living off the abundance of kelp-associated ecosystems, and camping out in these hypothesized ice-free areas, possibly as early as 20,000 years ago, or more.

Adam Huggins 13:25

One thing we're not going to do in this episode is make any kind of definitive statement about the peopling of the Americas. There are so many peoples and so many stories, so many possibilities, including long distance canoe travel by Pacific Islanders, or even theories that involve ancient peoples crossing the Atlantic. But we are in love with the idea that kelp ecosystems have played such a profound role in the deep time origins of coastal peoples, and that these ecosystems are still so important to us today. In fact, We're in love with kelp ecosystems in general.

Mendel Skulski 14:03

So in this final episode of our series on kelp worlds, we're taking you to Gwaii Haanas, the Islands of Beauty, to explore how people who love these ecosystems, Haida, scientists, commercial divers, and podcast listeners alike, can work together so that when sea otters return to our shores, we'll be ready. We're calling this episode “In The Balance.” Hawa'a for listening.

[Music grows in volume]

Introduction Voiceover 14:33

Broadcasting from the unceded, shared, and asserted territories of the Penelakut, Hwlitsum, and other Hul’qumi’num speaking peoples, this is Future Ecologies, where your hosts - Adam Huggins and Mendel Skulski - explore the shape of our world, through ecology, design, and sound.

[Music fades rhythmically]

Adam Huggins 15:04

When we washed up on the shores of Haida Gwaii last summer, the first thing we did was head over to the Haida Heritage Center.

Mendel Skulski 15:11

No, the first thing we did was gorge ourselves on the thousands of ripe thimbleberries literally lining the streets of Queen Charlotte.

Adam Huggins 15:19

[laughs] Yeah, that's actually much more accurate.

Mendel Skulski 15:22

Yeah, it was basically heaven.

Adam Huggins 15:25

The streets of heaven are lined with fruit, not gold. [more laughter]

Mendel Skulski 15:28

Yeah. But we digress. The second thing we did was head over to the Haida Heritage Center, also known as the Ḵay Center, where a truly magical thing happened. A very nice young lady working there, aptly named Hannah Freegan, offered us a rare treat.

Mendel Skulski 15:46

[on-site recording] Okay. What what are we about to try?

Hannah Freegan 15:50

K'aaw.

Mendel Skulski 15:51

What is k'aaw?

Hannah Freegan 15:52

It is herring roe on kelp, giant kelp.

Adam Huggins 15:55

Attentive listeners may remember k'aaw from Barbara's waxing on kelp as food. Not just in its own right, but also as a substrate for herring to lay their delicious eggs on. Unfortunately, though...

Mendel Skulski 16:07

Ah, where is the k'aaw from?

Hannah Freegan 16:09

[laughs] It's from Bella Bella. Actually, we don't have a lot of kelp around our waters here. So a few guys every year bring up k'aaw and sell it to us. Because we can't harvest it a lot, here.

Adam Huggins 16:27

This is due, in part, to declines in herring populations due to overfishing, which as we've said previously, we hope to talk about in the future. But it's also just due to a general lack of kelp.

Hannah Freegan 16:39

We just don't have enough kelp for them to lay their eggs on the kelp. So they lay their eggs elsewhere, but just we don't have enough kelp to harvest them on. Yeah.

Adam Huggins 16:50

That's interesting. So, do you think there would be a lot more k'aaw if there was a lot more kelp?

Hannah Freegan 16:54

Yes.

Mendel Skulski 16:55

That sobering knowledge did not stop us, dear listeners, from chowing down.

Adam Huggins 17:01

[chewing sounds] It's like having bouncy balls in your mouth. [laughter] Jump in there, get some.

Mendel Skulski 17:12

You can have as much as you want, I'm sure.

Adam Huggins 17:14

It's got a good flavor.

Hannah Freegan 17:15

Yeah, it's definitely one of my favorite foods.

Mendel Skulski 17:18

[laughing] I like how the first two things we do involve eating.

Adam Huggins 17:22

It's very on brand. While on Haida Gwaii, we sampled thimbleberries, and cloudberries, and crow berries, and salmon berries, and k'aaw, but we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Mendel Skulski 17:35

That's also on brand. [laughter]

Adam Huggins 17:40

So, coming back to k'aaw, the knowledge that there wasn't enough kelp or herring left in Haida waters to support a k'aaw fishery stuck with us as we set out early the next morning to explore Gwaii Haanas, which means Islands of Beauty in Haida and essentially refers to the southern half of the archipelago. We were part of a media expedition organized by Parks Canada.

Mendel Skulski 18:06

That's right. Yours truly, we humble podcasters, are now officially card carrying members of the media establishment. We've made the big time.

[Jazzy swing music]

Adam Huggins 18:22

The big time, in this case, involved an early morning ferry ride from the island metropolis of Queen Charlotte across to Sandspit, which is more or less like it sounds, followed by a long ride in a van stuffed with journalists and Parks Canada employees.

Adam Huggins 18:38

[In van] So, we've got an hour and a half of this.

Adam Huggins 18:41

Is that right? [laughter] All right.

Fellow Journalist 18:44

Minus the ten minutes we've been going.

Mendel Skulski 18:46

Anyhow, the van dropped us off at the head of Cumshewa Inlet, which you might remember is where Barbara Wilson is from, and there we suited up, piled into a Zodiac, and set off on our journey, led by our fearless captain, Ollie Popley.

[Jazzy music ends with a flourish]

[Sounds of a boat motor]

Mendel Skulski 19:10

As soon as we get underway, though, we pass through Louise Narrows, a small channel in between two much larger islands, and it forces us to slow down to a crawl. This gives Ollie a moment to tell us a little bit more about Gwaii Haanas, because depending on who you ask, you'll either hear it called Gwaii Haanas, or you'll hear…

Ollie Popley 19:31

Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, Haida Heritage Site, and Marine Conservation Area Reserve.

Adam Huggins 19:38

Good god, what a mouthful.

Ollie Popley 19:39

And the "reserve" part is really important because it indicates that relationship between The Council of the Haida Nation and the Government of Canada, and it basically shows that they both agree to disagree upon who owns it. What they do agree on is that it should be looked after.

[Pensive arp synth begins, low]

Mendel Skulski 19:59

From the minute we set foot on Haida Gwaii, we could tell there was something different about this place. Almost all of British Columbia is the unceded territory of one or sometimes several First Nations, not to mention the rest of Canada or North America, which one could frame as anything from covered by treaty to expropriated by legalistic obfuscation to just plain stolen. But Haida Gwaii just feels different. It feels as though, in this one far flung place, Canada and the Haida have settled on a temporary truce over who the land belongs to.

Adam Huggins 20:40

Which is a polite way to say that everyone recognizes that the land belongs to the Haida Nation and has since forever, but that the Government of Canada is trying to maintain a legitimate presence there while treaty negotiations are underway. It sounds tense, and I'm sure at the negotiating table it can be. But out on the land and water it feels kind of miraculous. Like an actual living, breathing example of co-management of ecosystems that draws on the strengths of two very different cultures. Within the reserve, ecosystems are protected from mountaintop to the sea floor, with 100% of the land protected from logging and other extraction and 42% of the water protected from commercial fishing, with the entirety of the reserve open to Haida traditional use. So whether you call it Gwaii Haanas...

Mendel Skulski 21:36

...or The Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site...

Adam Huggins 21:44

...it sets a powerful precedent for the way ahead. And that's in part why we're here. But as we emerge from the Louise Narrows and shoot out into more open water, Lyell Island comes into view in the distance. And as we approach, we are reminded that this spirit of cooperation wasn't always here.

Mendel Skulski 22:08

In the 1970s, logging practices on Haida Gwaii, then known as the Queen Charlotte Islands, were like logging practices pretty much everywhere else in BC: unsustainable at best, destructive at worst. By 1985, after a decade worth of nation to nation negotiations to try and protect the area now known as Gwaii Haanas, a local logging outfit headed by a man named Frank Beban was preparing to move in and clear cut an important cultural and ecological area called Windy Bay on Athlii Gwaii, or Lyell Island. What happened next was nothing short of historic and to tell the tale, here's Haida elder and living legend, Captain Gold.

Captain Gold 22:53

So we had a quick emergency meeting in the fall in 1985. Buddy was asking people that attended the meeting, he said, "what do you people think? He’s ready to get into Windy Bay, what are we going to do?" He was looking for kind of directions, I guess you could call it. So right away, we all said, "enough is enough. We got to move now. We got to stand behind our word." All those things like that you could hear from people. So the word was out: we're going to stop logging. We're going to stop Beban.

Mendel Skulski 23:29

In October of 1985, Captain Gold and a group of young Haida head down to Windy Bay to occupy the cut block and make a stand.

Captain Gold 23:38

So we started organizing and pulled together a building crew and ah, who are the cooks and who are the volunteers? And.... The first building to go up was a cook house. And then the second one was the honeymoon shack, which is a bath house. [laughs] And then the other one was the snake pit, we called it, which is where everybody gets in from all over, either were coming in to spend the night, and go up on the line the next day and get arrested, shipped off. Another group comes in, starts over. That's why we were calling it the snake pit. [laughs] What it place it was, it was so powerful.

[Sounds of water and drums]

We heard that Frank Beban's going to go logging the next day, so we asked the ladies in the camp to leave us and all the men stood in the room, joined hands. Then we started prayers and then we started Haida singing. It was pretty powerful for a lot of us in the way that, we all expected to be away for two years, so we were making arrangements with some people about how to look after our affairs when we're gone. And the ladies outside were waiting, so we invited them back in and they said they were moved to tears to hear us singing, because we're all singing in the one big group. The next day, because I was the oldest one, I went up there. They elected me to be in front of the line. No use taking pictures at that point. We all expected to be hauled away.

[Drum beat, sound of helicopters]

And then all of a sudden I could hear the chopper coming, and it turned out to be the five elders that stepped off the chopper right in front of us. That ended my role. I went back to taking pictures [laughs] and recording. Everybody was so happy to see them. In no time at all we added a little shelter on the road and a fire and little blocks of wood for the elders to sit on. [laughs] That started everything from there. It is a very emotional night because that first day they showed up, no other loggers showed up. At that point we had waited all day. So we all went down and we had supper and all that. And then the elders were very, very strong in their position. "We are going to be the first ones to be arrested." And we tried to talk them out of it. They wouldn't listen, they were wanting to go. [laughs] So they said, the elders anyhow, told us the reason why. That the rest of the world seeing us getting arrested, standing up for our rights and Haida Gwaii is going to be a very strong message to the rest of the world.

Media Clip 26:37

[singing, drumming] Last Wednesday morning, a group of Haida came to Sedgwick Bay on Lyell Island, to protect this lifestyle.

Archival: Logger 26:44

You're breaking the law and you're stopping us from going to work, and we ask you to step aside and let us continue.

Archival: Haida Person 26:52

There will be no logging on the area that the Haida people have designated is not to be touched. This is Haida land and there'll be no further logging in this area.

Captain Gold 27:00

Then everybody else started getting arrested after that.

Mendel Skulski 27:11

The arrests continued until winter, and the loggers eventually backed off. This victory precipitated a series of events that would result in the protection of the southern archipelago and the creation, in 1993, of Gwaii Haanas.

Adam Huggins 27:26

Long story short, Gwaii Haanas didn't just come to be on its own. It's the result of generations of Haida continually asserting their sovereignty, putting their bodies on the line, and using every tool at their disposal to defend their lands and waters and protect their culture. And to give credit to the good folks at Parks Canada, the relationship that has been built between Haida, scientists, and park staff, I'm sure it has its challenges, but it appears on the whole to be genuinely positive and its roots go back a good three decades, before reconciliation became a buzzword.

Mendel Skulski 28:08

We are about to arrive at Float Camp. So we'll have to move on for the time being. But this won't be the last we'll hear from Captain Gold in this episode or on this podcast

So, in just the first half of this episode, we've talked deglaciation, coastal migration, cut block occupation, and reconciliation. But as our little zodiac makes its way south through the waves and the fog and the occasional driving rain, the sun miraculously comes out from behind the clouds. And we round a corner into a sheltered cove for a very welcome sight. There's a series of floating buildings connected together to form a laboratory and field station. We see some distant figures on board waving and beckoning us over and we are very happy to be pulled in.

[sound of people calling hello]

Voice from the zodiac 29:30

We're just fashionably late.

Voice from the field station 29:33

I know, we tried to call you!

Mendel Skulski 29:35

Adam, in particular, was happy to come ashore. I think it's safe to say he is definitely not a sailor.

Adam Huggins 29:44

[laughter] It's good to have legs.

Mendel Skulski 29:48

And we were delighted to see a familiar face.

Lynn Lee 29:51

[field recording] Good to see you too.

Adam Huggins 29:55

This is Dr. Lynn Lee. And it was her presentation at a conference I attended last year that set this whole series into motion.

Lynn Lee 30:03

Okay, my name is Lynn Lee and I am the marine ecologist at Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site. I'm the technical lead for the Chiix̱uu Tll iinasdll project, which is Haida for "Nurturing Seafood to Grow."

Mendel Skulski 30:18

Which is basically what we'd come here to see. How exactly Lynn and her team are nurturing seafood to grow, in a nutshell.

Adam Huggins 30:26

How about "in an urchin test"?

Mendel Skulski 30:29

Nice.

Adam Huggins 30:29

Just "testing" it out.

Lynn Lee 30:30

Essentially, we're mimicking sea otter foraging, without foraging on abalone. So we're selectively foraging on the super heavy duty grazers, a lawnmower sea urchin, but we're not eating abalone.

Mendel Skulski 30:44

My goal there is to...?

Lynn Lee 30:46

It's to restore kelp forests and also to improve abalone habitat because of the indirect benefits of kelp forests for abalone, because they're known, like, if you have abalone in a kelp forest, they've been shown to have a different size structure than those that are outside the kelp forest.

Mendel Skulski 31:00

So cool.

Adam Huggins 31:01

So much work.

Mendel Skulski 31:03

Right. So, I guess we should unpack that. In the simplest terms, as we learned in Episode One, without sea otters to eat them, sea urchins basically clear cut kelp forests. So, remove the urchins yourself and presto: kelp. No sea otters required.

Adam Huggins 31:21

Lots of interns required.

Mendel Skulski 31:22

But in this case, they've actually partnered with the Haida and with commercial urchin divers, so a little less work. But, still a lot of work. So basically, they chose two sites that were both urchin barrens.

Lynn Lee 31:37

You don't see it when you just look at an urchin barren, but there's always kelp settling. So, but as soon as it settles, then the urchin comes and gobbles it up.

Mendel Skulski 31:45

And in one of those sites, they sent a team of divers in to literally grab every visible urchin and [crushing noises] basically just crushed them with this specialized tool they had to buy from Japan.

Adam Huggins 32:01

The Japanese love their uni.

Mendel Skulski 32:03

Well, me too. And after all the urchins within the area are gone, that's it. They resurface and just watch and wait.

[jazzy flair of music]

And if their hypothesis is correct, then the area they treated should become a kelp forest within a matter of months, while their control area where they didn't remove any urchins should remain an urchin barren. It's a pretty simple and elegant experiment.

Dan Okamoto 32:31

Yeah, so the initial urchin cull started in September of 2018. And then the larger cull happened in March of 2019. So the urchin harvesters came out and helped clear thousands and thousands of urchins from that three kilometer stretch.

Adam Huggins 32:45

This is Lynn's colleague, Dan, who is focusing on the urchin side of the equation.

Dan Okamoto 32:51

Yeah, my name is Dan Okamoto. I'm an assistant professor of Biological Science at Florida State University.

Mendel Skulski 32:55

It's a long way to come to bust some urchins.

Adam Huggins 32:58

He's committed. But what's really cool about Dan's work is that he's studying the urchins to see if restoring the kelp forest, like, does that transition from urchin barren to kelp forest benefit the urchins, even though, by necessity, there would have to be a lot less of them for it to happen?

Dan Okamoto 33:17

And one of the questions is, if you restore a kelp forest, does that actually have much impact on their diet? Does that have an impact on their growth rates? So one of the chemical analyses we're doing is taking tissue samples, and we can use fatty acid analysis to look at the different fatty acid compounds that are in those tissues that are incorporated from their food sources. And then do the same thing with their food sources, and we can try to understand, is there a shift as you recover a kelp forest and there's lots of other different kinds of food around, how does that shift and how does that compared to the areas that haven't been impacted?

[Background music fades in]

Mendel Skulski 33:50

This is kind of a complicated way of saying, "You are what you eat, urchins. And so we're going to study what you eat, and see how that changes in a kelp forest versus an urchin barren." And they're using fatty acids because they provide a really detailed index for what the urchins are eating over time. Dan's student, Nate, explained this really well.

Nate Spindel 34:12

If you get kind of a time integrated value, as opposed to seeing, "oh, that's what they're eating right now." Or you take it one step better, and you take maybe their gut contents and say, "well, that's what's in their stomach." Just because I found a cheeseburger in your stomach yesterday...

Lynn Lee 34:26

[laughter] Today!

Nate Spindel 34:28

...today, doesn't mean you eat cheeseburgers every day. [laughter]

Lynn Lee 34:29

What?! What are you talking about.

Nate Spindel 34:29

So it's kind of a, it's just kind of a cool way to see what, you know, on average, what they've been eating over time.

Adam Huggins 34:38

Also, if you've ever cracked open an urchin, the test is basically hollow and filled with their food and digestive juices. It's kind of gross. [laughter from Mendel]

Dan Okamoto 34:48

They're quite inefficient. So generally, you know, it's almost like their poop looks like what they eat, in smaller form. [laughter in the background]

Adam Huggins 34:55

So, they don't have full results yet because they're still doing the research, but one thing they have shown, by putting urchins in these cool chambers that measure gas exchange and temperature, other things like that, is that urchins and urchin barrens essentially go dormant metabolically. Like, they go into hibernation or something like it.

Dan Okamoto 35:19

We measure the metabolism, and urchins from urchin barrens just shut down. It's kind of this cool observation...

Lynn Lee 35:25

They're in deep meditation. [laughter]

Dan Okamoto 35:26

They're in a deep meditative state.

Adam Huggins 35:28

So a little bit non responsive?

Dan Okamoto 35:30

I mean, they are... they're just cruising.

Lynn Lee 35:31

They just vary the breathing rate. So, there's a respiration rate that the chambers are measuring. So you put individual-- You can see them. Nate's just gonna run the experiment, but you put an individual urchin into the chamber and then it's hooked up to things that measure the gas content, and then you can tell how much it's used, breathing essentially, in the water. And so the ones that they're getting from the kelp line, which is where all the food is, have a much higher metabolic rate than the ones that are doing down low where there's more food.

Dan Okamoto 36:01

The urchins down deep also can be voracious. So that's plenty sufficient to suppress any new growth. Right? So, we call them zombies. They're just in a state where there's not much roe, somehow they're still there...

Lynn Lee 36:16

[laughs]

Dan Okamoto 36:16

I've kept urchins alive in the lab for up to a year without feeding them. It's not very nice, but it happens.

Mendel Skulski 36:23

Did you give up or did they die?

Dan Okamoto 36:24

I had to graduate from my PhD... [laughter]

Mendel Skulski 36:30

So, these herds of zombie urchins can live together with almost no food nearly indefinitely, which explains why without sea otters or very, very committed scientists wielding Japanese urchin crushing tools, kelp forests can't really come back on their own. And then Dan and Lynn told us something totally wild. Remember those atomic bomb tests on Amchitka back in the sixties and seventies? Researchers have been able to identify trace amounts of radioactive material from those nuclear tests inside of urchin tests, allowing them to determine that the large red sea urchins so common off our coast can be over 100 or even up to 200 years old. Some may be old enough to have been a wee pluteus when sea otters were still around, before they were hunted into local extinction, which kind of blew Adam's mind.

Adam Huggins 37:29

Like, I was just thinking about the urchins and it's like, if those urchins are 100 to 200 years old, like... that's an old growth forest in a sense, like an old growth animal ecosystem.

Dan Okamoto 37:39

An urchin zombie forest? [laughter]

Adam Huggins 37:41

Yeah, an old growth urchin zombie graveyard. I don't know what to call it. It just struck me in that moment that the so-called "forests" of bull kelp we're trying to revive here are short lived ecosystems in a sense. Like, they can be stable over decades, but the bull kelp itself is just an annual species: it grows and reproduces and dies each year and it has to do it again the next year. Even the oldest kelps only live a few decades at most. And yet, urchin barrens can be composed of some individuals that are hundreds of years old, making them old growth by any definition, zombies or not.

Mendel Skulski 38:22

But even though kelps themselves are short-lived, the ecosystems they create are ancient and full of life, and probably overall a better place for urchins to live in. And you can't make a kelp forest without cracking a few urchins. Speaking of which, we couldn't move on from the topic of urchins without sampling some of Dan's specimens. As we mentioned previously, the edible parts are actually the urchin's gonads, which on a healthy, that is, non-zombie, urchin, are arrayed in these juicy crescents around the inside of the test. We started with a large red one.

Dan Okamoto 39:00

We want one that's full, that's healthy, that's well fed, lots of liquid content. And they're really, really sweet if they're fat and happy.

Adam Huggins 39:10

Let's see... Yeah. [squelch]

Mendel Skulski 39:17

Oh I love it. Oh my god, I love it.

Mendel Skulski 39:20

And then we tried one in the diminutive, but numerous green urchins.

Dan Okamoto 39:24

So the greens are far more consistent and generally tend to be sweeter, so people prefer them.

Adam Huggins 39:30

Oh, that's even sweeter than the red ones. Mm. That is so good! Ohhhh...

Adam Huggins 39:38

But before we could get to the purple sea urchins, we realized that Dan had more than just urchins hiding in those chambers of his. [music fades out]

Dan Okamoto 39:48

Yeah. So we're trying to keep him happy with some of the kelp here. These are kind of little guys, but... Yeah. So these are endangered, right?

Adam Huggins 39:58

This is the northern abalone, right?

Dan Okamoto 40:00

This is northern abalone, this is the Pinto abalone. And they eat basically all sorts of… they eat kelp, they eat stuff that's growing on the rocks. And so the idea is that as you remove a bunch of sea urchins, you get a bunch of kelp coming back, in theory, that might help boost abalone populations, increase that growth rates, increase their reproduction, increase their survival.

Mendel Skulski 40:21

And then Lynn brought one out to show us.

Lynn Lee 40:24

Here, you can see this one's coming out.

Mendel Skulski 40:26

My god.

Lynn Lee 40:26

So the eye stalks are coming out. You can see the little black spots there. Yeah, so they can see light and dark. And there's its head. They're actually the fastest nail in the west. [laughter] I like to tell people that little fun fact.

Adam Huggins 40:41

Dubious distinction.

Lynn Lee 40:42

Yeah, dubious distinction, but they do move quite fast when they're running away from predators. Oh, this guy's really performing. This is awesome.

Adam Huggins 40:49

Northern abalone are more beautiful and active than I had ever imagined. More so even then their lustrous shells had suggested. Picture a large, dark, totally flattened slug, encircled by this border of fringed epipodia, known as a skirt. It has little eye stalks and a radula for grazing on the head, and the entire thing is topped with a flat shell that has an arc of holes in it, which they use for all the things.

Lynn Lee 41:23

Yeah, everything... so they breathe through the holes, they spawn through the holes, they... [laughs] the holes are useful.

Adam Huggins 41:29

I was so taken aback by how charismatic this little sea snail was that I couldn't resist.

Adam Huggins 41:36

[on-site] Do you mind?

Lynn Lee 41:36

No, not at all!

Adam Huggins 41:38

Oh my goodness.

Lynn Lee 41:39

Yeah. Isn't that cool?

Adam Huggins 41:41

That is such a cool sensation.

Lynn Lee 41:43

Yeah. So if you just let it go and don't disturb it... [laughs] Isn't that cool?

Adam Huggins 41:50

The closest thing I can describe is like, ah, goats eating out of your hands. You know?

Lynn Lee 41:55

That I have not done before.

Adam Huggins 41:56

Oh yeah?

Lynn Lee 41:57

That one's pretty cooperative. I think this abalone wants to be your friend.

Adam Huggins 42:02

I want to take this home with me.

Lynn Lee 42:06

You may not take your abalone home, I'm sorry. [laughter]

Mendel Skulski 42:11

And of course, I had to get in there too. [laughter from Lynn]

Adam Huggins 42:17

Isn't that awesome?

Mendel Skulski 42:19

Yes, awesome is the word for this. Oh my gosh.

Lynn Lee 42:24

You both have been rarely blessed by an abalone.

Mendel Skulski 42:27

They just articulate their shell so much.

Lynn Lee 42:29

Oh yeah, so this is really cool too, this twisting action. So when they're trying to get away, so imagine you're a sunflower star and your two feet are coming up and you grab the abalone. So one of its escape responses is to twist back and forth really vigorously. And then it can pop the two feet loose and then it can start to run.

Mendel Skulski 42:45

Defensive action. So cool. Wow.

Mendel Skulski 42:49

[in studio] This is where the medium of podcasting fails us. But this energetic little abalone flexes its foot when it's alarmed, and it twists its shell above itself in a helicopter motion. It's actually really strong. When we first started talking to Lynn and Dan, it was hard to imagine doing all of this work, just to help a snail make a comeback. But that little snail stole our hearts.

Adam Huggins 43:16

And unlike most things on Haida Gwaii, we didn't even get to taste it!

Mendel Skulski 43:20

No. Instead, we put our wetsuits on, jumped back in the boat, and went out to see the research sites.

Adam Huggins 43:31

[boat sounds] Isn't it beautiful?

Mendel Skulski 43:32

Where's my goggles at?

Adam Huggins 43:33

It's so beautiful.

Mendel Skulski 43:35

They're on my arm.

Adam Huggins 43:37

Could you describe what we're looking at.

Lynn Lee 43:39

Okay, so we are sitting in the northeast side of Murchison Island. And that's right in our restoration site. We have two permanent sample plots where we run transect lines here, and what you're looking at is all the new kelp growth since we have removed the urchins.

Mendel Skulski 43:56

And what does it look like to you?

Lynn Lee 43:58

So, it's a lush bull kelp forest, a canopy that extends out from shore probably about five to ten meters. Previous to the restoration work, we maybe had a couple of plants against the shoreline. So this is like a really big increase in the canopy that has happened since we did the restoration work this spring.

Mendel Skulski 44:19

Wow. So how long has it been?

Lynn Lee 44:21

So, between nine and three months, three to nine months. All this kelp has grown back, which is pretty phenomenal. So we're really excited.

Mendel Skulski 44:29

I'm really curious, why did you choose this site to be your test block?

Lynn Lee 44:32

Well, we had two purposes for this: we wanted to improve abalone habitat. So we wanted places where abalone were living. And so this is a good place for abalone. And we also wanted to be on a rocky shore where there was already potential for good kelp forests to come back. And so this is part of the reason we chose the site. So I hope you guys enjoy your snorkel because the sunlight is streaming through and so you should be able to see lots of fish swimming in there.

Adam Huggins 44:59

Looking forward to it.

Mendel Skulski 45:01

I'm unspeakably excited.

Lynn Lee 45:03

I think you should just get your stuff off and jump in the water. [laughter]

Mendel Skulski 45:06

Sounds good. [splashing and a "woohoo!"] It's so buoyant!

[meditative music comes in]

Adam Huggins 45:17

I'm not sure how to communicate about that time in the water, except to say that the sun was shining, and these 20-foot-tall stipes of bull kelp were so thick in the water that we got tangled up in them. And there were these huge basketball sized fried egg jellyfish that were swimming around in there and they didn't really sting so you could just put your hand on them and kind of dribble them... like, like they were basketballs or something. [laughs in awe]

Mendel Skulski 45:52

It was so dense that you wouldn't even see them until you got right on top of them. The kelp is so much thicker and stronger than I expected, it was a lot more like... like climbing than like swimming. It was so magical. We weren't able to dive down to the bottom, where we could see all these schools of fish and kelp crabs floating on the fronds. But it was just so easy to imagine that instead of this little patch, that there could and should be extensive underwater forests like this all along the coast. Well, let's just say we've become true believers.

Adam Huggins 46:36

We also got to swim in their control site, which was similar except that they hadn't removed any urchins. So there was literally no kelp at all. And it looked like a bunch of urchins, hanging out and not doing too much. Pretty docile for a zombie hoard, all things considered.

Mendel Skulski 46:56

And that that's not to suggest that nothing of ecological or human value is happening in that urchin barren, but we both definitely had this immediate visceral reaction of joy in that kelp forest. And I'm honestly still carrying it to this day.

[Music swells, conveying their awe]

Adam Huggins 47:30

When we got back in the boat, shivering because the Pacific Ocean is as cold as it is exciting, we may or may not have spent the rest of the afternoon soaking in the fabled pools of Hotspring Island, just across the way. But that's for us to know and you to imagine.

[Music fades out]

Now, I hate to burst this bubble, but in case any of you were wondering, the methods Lynn and Dan and their team of Haida and commercial fishermen are employing to bring back the kelp forests and the abalone? They're straightforward and effective, but probably impossible to replicate at scale. I followed up with Jim Estes, the father of kelp forest ecology who you heard in Episode One, and asked him point blank if he thought kelp forests on the coast could be restored in this manner, without otters.

Jim Estes 48:26

You want a real frank answer? You're pissing against the tide. I mean, god no, I don't think so. So no, I think going out there with hammers and whatever all they're doing, killing urchins, I mean, it does show a process, but as a management tool to try to recover that system to a kelp dominated system... It seems, it seems silly to me, I just cannot imagine that. You know, it would take such a vast effort. So, I think if you want that system to be a kelp dominated system, which a lot of people do, because they value kelp as a habitat for other species, and so on and so forth, you're probably going to have to get the full complement of interactors back that make it kelpy.

Mendel Skulski 49:08

I want it more kelpy. One more vote for kelpy.

Adam Huggins 49:12

Vote for kelpy. [laughing]

Mendel Skulski 49:14

Vote for kelpy.

Adam Huggins 49:15

Yeah, I'm with you. And to be clear, Jim's not criticizing the Gwaii Haanas experiment at all. He's aware of it and he's following the research. He's just acknowledging that the methods aren't practical at scale. You need to have sea otters or other urchin predators in the system to make it kelpy in the long run.

Mendel Skulski 49:36

So why do this experiment at all? Well, there is something we haven't told you yet. The official Gwaii Haanas crest, the logo you see everywhere on Parks Canada materials and on signs around Gwaii Haanas, is of a sea otter floating on its back with an urchin balanced on its belly.

[Music begins in the background]

And just a reminder, there still aren't any established sea otter populations in the waters around Haida Gwaii. And there haven't been for over 200 years. We were curious about this. And so, naturally, we asked Captain Gold about it.

Captain Gold 50:13

Gitkinjuaas. Chief Gitkinjuaas. Ron Wilson.

Mendel Skulski 50:18

It's a beautiful image, done in the northwest coast style by Haida artist Gitkinjuaas, Ron Wilson. And according to Captain Gold, Gitkinjuaas came to him to ask his advice on what to do.

Captain Gold 50:30

He said, "I'm stuck." He said, "I can't think of how to make this logo," something like that. And I said, "just think!" I said, "what represented the wealth of Gwaii Haanas? It's the sea otter. And you picture him laying on his back, so he's always in the ocean, and what food is he always eating? A sea urchin." I said, "do you remember the sun? And it looked just like the sea urchin with all the spikes and whatnot. That's the rays of the sun." So he did that design and that became the logo.

Adam Huggins 51:14

In many ways, the crest is both a reminder of what's been lost, and also it feels somehow aspirational. Like this could be the reality in the near future. Because sea otters have successfully reestablished themselves in and around Vancouver Island, the central coast of BC, southeast Alaska, Haida Gwaii is surrounded. And most scientists now agree that it's only a matter of time before sea otters form viable populations on Haida Gwaii. It could really happen any time. And people do occasionally see wandering males scoping out new territory.

Captain Gold 51:56

For years I watched a sea otter down at Skagway, never said a word to anybody. And I seen another one recently in a different place. But I kept mum about that too. And you find them here and there, slowly starting to come back.

Mendel Skulski 52:15

The reason that Captain Gold tends to keep these observations to himself is that many Haida and commercial fishermen are afraid that if the sea otters return, then they'll eat all the seafood, and there won't be anything left for people. And that's not an unreasonable fear. As we learned in our last episode, from talking to Kii'iljuus and Anne, it's already happened to the Nuu-chah-nulth on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Captain Gold 52:41

And they keep using that as a picture. If we allow sea otters to come back, it'll be like Vancouver Island.

Adam Huggins 52:49

The central question here is, once the sea otters return, will it be possible to strike a balance between making things kelpy again, and having enough food to support the otters, but also preserving and maybe even enhancing people's ability to sustainably harvest seafoods? The abalone isn't the only important food. But it's sort of the canary in the coal mine here.

Dan Okamoto 53:15

And the funny thing about abalone, right, is one of these things where otters come through, and they'll eat the urchins, and kelp forests will come back, but otters also love abalone, so... So it's one of those trade-offs, right, where you can recover the, you might be able to help the kelp populations, but basically, it's a double whammy. Like, these guys are kind of damned if you do, damned if you don't. They've got a dominant competitor that eats their food source, and they've got a dominant predator that eats both of them.

Adam Huggins 53:40

The health of its populations are an indicator for the balance that we as people would want to strike. So much so that when the Haida and Parks Canada got together to articulate a set of guiding principles for caring for Gwaii Haanas, they chose abalone to represent balance. The sea otters may return sooner, or they may return later, but if abalone can't be preserved, then we still haven't found that right balance.

[Music ends]

Mendel Skulski 54:24

As we made our way back from Float Camp to town, we stopped at Windy Bay on Athlii Gwaii, also known as Lyell Island. This is the watershed that Captain Gold and the Haida formed a blockade in the 1980s to defend, and it's full of these incredible, huge old growth trees. There's also a longhouse there and next to it, the legacy pole, which was raised in 2013, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Gwaii Haanas agreement. We'd been traveling this whole time with these two young Haida women, Crystal and Shayanna, who were also working for Parks Canada that summer.

Crystal Young 55:00

See in the middle there?

Mendel Skulski 55:01

They sat down to tell us the story that the legacy pole was made to communicate.

Crystal Young 55:06

It is the three watchmen. And it's to honor all those watching over Gwaii Haanas in the past and future.

Mendel Skulski 55:14

It struck us that these young Haida in Parks Canada uniforms were themselves emblematic of this remarkable agreement of cross-cultural cooperation and co-management, guided by a set of shared values that feels very open ended. And then, as they wrapped up, we noticed that there were abalone shells literally embedded into the legacy pole.

Adam Huggins 55:41

It seems that everywhere we go, there's abalone.

Crystal Young 55:45

It's definitely in our guiding principles, that Gwaii Haanas was set out to have. The abalone is to represent a balance between the interactions between the natural and supernatural but also between, like, the land and sea.

Adam Huggins 56:00

Have you guys tasted abalone? Or has it always been protected?

Crystal Young 56:03

It's always been protected, since I was born at least.

Adam Huggins 56:07

Which is, how old are you?

Crystal Young 56:08

20.

Adam Huggins 56:12

It's striking to think about the cultural and ecological significance of abalone, how present they are in the art and culture and oral history of the Haida and other coastal people. And yet how absent they are from the ocean, and from the diets of this new generation. When I hear Captain Gold say something like:

Captain Gold 56:36

It's so late for a lot of things in our world – traditional foods.

Adam Huggins 56:42

I really start to understand what is meant by calling the Gwaii Haanas project "Nurturing Seafood to Grow". And for Lynn, who's been studying the system in Gwaii Haanas, the way to do that is pretty clear.

Lynn Lee 56:56

Well, my perspective is that the return of sea otters is a chance to restore traditional harvest of sea otters and traditional harvest of abalone and kelp beds. So, to restore that balance of people using the ecosystem in ways that they had before. So, it's in those, in the areas where sea otters have come back, where there's been no hunting, then you get the other extreme of the ecosystem too, which is different than what it was in the past when people were also actively hunting sea otters throughout the coast. So we've bumped it to like a total other end of the spectrum, with letting sea otters survive and grow at exponential growth rates as much as they can, with no predation, no human predation, which was part of the system and actively part of the system. So my perspective here is that sea otters are, they're very polarizing in the community, so there's some people who want to shoot them as soon as they see them and other people who recognize that they benefit kelp forests and benefit the ecosystem. And so there are two camps. But ultimately, I think we're gonna get to the point where otters come back, they reestablish, and we'll reestablish a hunt as well, when there's enough that you can have a hunt.

Mendel Skulski 58:02

Captain Gold is on the same page.

Captain Gold 58:04

And the sea otter and everything else is one that likes to eat the abalone. And we like to eat them. If we control both, we keep them for the future. And that's basically a lot of the things that we did in our cycle of life. But with the Ministry of Forests, ah Fisheries, commercializing all the food, we don't have it, there's no balance. We get fined if we even look at it. [laughs] So we have to convince Ministry of Fisheries and whatnot that we need to harvest. We have to harvest in order to try to keep that balance.

Adam Huggins 58:52

Harvest the sea otter.

Captain Gold 58:53

Yeah.

Mendel Skulski 58:54

And so, for now, Lynn and Dan will continue to study the effects of sea otters without any sea otters, and with an eye to how to help the abalone bounce back. And the Haida, and scientists, and Parks Canada will be watching closely for the sea otter to return. When it does, we will be watching Gwaii Haanas, because given the deep time role of Haida Gwaii as a hub on the kelp highway, given its unique cultural and political landscape, and the unprecedented level of cooperation between Parks Canada and the Haida Nation in stewarding Gwaii Haanas, we think that it's possible that this is the place where allowing the ecosystem to be kelpy doesn't mean depriving people of their traditional foods.

Adam Huggins 59:44

In neighboring Alaska, certain native hunters are allowed to hunt sea otters under a very restricted set of conditions, which has opened the door to management. But practically speaking, it's a drop in the bucket and hardly an ecosystem level plan. Many commercial harvesters in Alaska continue to call for a bounty on sea otters. Meanwhile, many conservation groups continue to outright oppose any hunting of sea otters. For them, it's a non-starter. So, as we draw this series to a close, we're just as unsure as anyone of exactly what the right balance of sea otters and sea urchins and abalone, and all the mesopredator predators like sunflower stars, which we didn't even get to talk about... not to mention human beings... What that right balance is. And it's almost surely going to vary from place to place on the coast. But looking back into deep time, the Haida and other coastal peoples were clearly able to strike this balance. So we're pretty sure that Indigenous peoples and scientists like the ones you've heard over the past three episodes, working together, are the best guides here. And what we're hearing is that, paradoxically, to bring the abalone back, we need to bring the sea otters back. But to bring the sea otters back, we need to be able to hunt them and keep them out of some areas. And to be able to hunt them, we need, in essence, the whole approach to the protection of endangered species to shift, at least where keystone species like sea otters are concerned.

Mendel Skulski 1:01:33

It's a tall order, but it's how we're gonna conclude this series. And since everyone knows that it ain't over until the kelp horn blows, we're going to ask Ollie to play us out.

Adam Huggins 1:01:46

[From zodiac] So wait, what are we hearing here?

Ollie Popley 1:01:48

Ah, this is the kelp horn.

Fellow Journalist 1:01:50

The bull kelp.

[Sound of bull kelp horn being trumpeted & laughter]

[Theme music kicks in]

Adam Huggins 1:02:01

Thanks for listening. This episode, and the Kelp Worlds miniseries of Future Ecologies, was produced by myself, Adam Huggins.

Mendel Skulski 1:02:14

And me, Mendel Skulski.

Adam Huggins 1:02:16

We covered so much ground and water. And yet, there's still so much more to talk about. From the recent spread of urchin barrens in Northern California, to the effects of sea star wasting disease on kelps, and the extinction of the stellar sea cow. Are you all kelped out? Or are you hungry for more next season?

Mendel Skulski 1:02:36

Vote for kelpy!

Adam Huggins 1:02:37

Any votes for kelpy? Let us know how you're feeling, if you made it with us to the end, at futureecologies.net

[Music flourishes]

Mendel Skulski 1:02:48

In this episode, you heard Captain Gold, Kii'iljuus Barbara Wilson, Lynn Lee, Dan Okamoto, Anne Salomon, Charles Menzies, Nate Spindel, Ollie Popley, Crystal Young, Shayanna Sawyer, Hannah Freegan, Stu Crawford, Jenn Chow, and Yarrow.

Adam Huggins 1:03:09

You can find more information about the Nurturing Seafood to Grow project on Gwaii Haanas's website. You can find pictures from the trip and all sorts of links and citations and tidbits on our website, futureecologies.net. And you can find journalist Jason Goldman's excellent piece on this topic in the online publications Biographic and The Narwhal.

Mendel Skulski 1:03:32

We'll be back next month. Please rate and review Future Ecologies wherever podcasts can be found. It helps a lot and we always like to know what you have to say. Special thanks to Miranda Post and Parks Canada, Chloe Clarkson, Winnie Tsai, Ollie, Stu, Jen, and Yarrow, Leigh-ann Fenwick and Kieran Wake, without all of this adventure would never have been possible. Seriously. Thank you.

Adam Huggins 1:03:59

Also, an extra special thanks to Riley Byrne over at Podigy for cleaning up all of our totally messy field recordings.

Mendel Skulski 1:04:06

Also, thanks to Nate for lending me a wetsuit.

Adam Huggins 1:04:09

Music in this episode was produced by the Hot Sugar Band, Aner Andros, Ben Hamilton, Hildegarde's Ghost, and Sunfish Moonlight.

Mendel Skulski 1:04:20

If you like what we're doing and you want to help make it happen, you can support us on Patreon. Pay what you can to get access to bonus monthly mini episodes, extended interviews, stickers, patches, and more. This season I'm guiding a tour of mushrooms and the kingdom fungi. Join the party: head over to patreon.com/futureecologies

Adam Huggins 1:04:39

You can get in touch with us on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and iNaturalist. The handle is always Future Ecologies. You can find a full list of musical credits, show notes, and links on our website: futureecologies.net. Thanks for listening. [music plays out]

Adam Huggins 1:05:12

Cool. That's it! I'm stopping this. [drum beats into silence]

Transcribed by https://otter.ai, and edited by Emma Morgan-Thorp and Victoria Kline